by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

Philologos Religious Online Books

Philologos.org

Chapter 25 | Contents | Chapter 27

Cunningham Geikie D.D.

With a Map of Palestine and Original Illustrations by H. A. Harper

Special Edition

(1887)

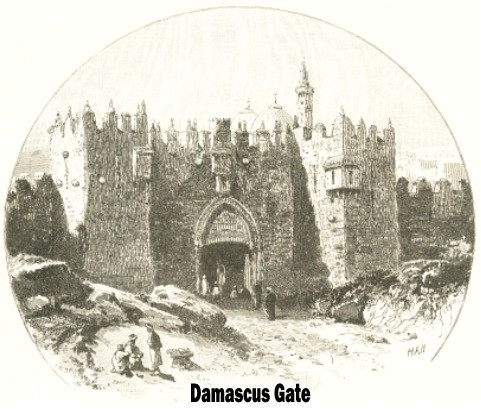

A few steps from what seems so reasonably to be identified as Calvary bring you to the Damascus Gate, which lies at the bottom of a slope. There is of course only the natural surface for travel; made roads being virtually unknown where the Crescent reigns. A short distance from the gate large hewn stones lie at the side of the track, the remains of some fine building of past ages, now, like so many others, utterly gone. On one side the road has a steep bank, several feet deep, with no protection; on the other ledges of rock now and then crop out. Balloon-like swellings from the flat roofs, beneath which only a few small windows are to be seen; the tall mosque of the dervishes, east of the gate; some minarets; the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and that of the Mosque of Omar,* fill up the foreground; the yellow, bare slopes of the Mount of Olives, dotted still with the tree from which it takes its name, and the pink mountains of Moab, with the lights and shadows of their heights and hollows, close in the horizon. The gate itself is a fine, deep, Pointed arch, with slender pillars on each side, and an inscription above stating that it was rebuilt in the year AD 1564. The front, on each side, is in a line with the walls, though a little higher, but a square crenellated tower of the same height as the centre juts out on either side, with a projecting stone look-out near the top, at the corner of both, in shape like a small house. Excavations show that there has always been a gate at this spot. A reservoir and a fragment of an ancient wall have been brought to light close by; and underneath the present gate there still exist subterranean chambers, of unknown age, the surface level having been greatly altered in the course of time. Facing the north, this, the finest gate of Jerusalem, has derived its name from the trade between the city and the distant Syrian capital. Situated at the weakest part of the town, where alone an enemy can approach without natural difficulties in his way, it has always been strongly fortified. It was, almost without doubt, through the gate which stood on this spot that our Lord bore His cross (Heb 13:12); and it was through this, also, that St. Paul at a later date was led away, in the night, to Cæsarea (Acts 23:31); for, as I have said, the great military road to the north must, in all ages, have begun at this point.

The ground rises very gradually towards the west from the gate; the wall running along very imposingly over the rough heights and hollows of the natural rock. A long train of camels, tied one behind another, with huge bales of goods on each, and a man riding the first and the last, two or three travellers on asses, and one or two on horses, all of them thoroughly Oriental in dress and features, paced northwards as I turned from the dried mud which does duty for a road, with its immemorial neglect on all sides, and rode on towards the Joppa Gate. With a few short intervals, some fields of no great breadth run along the outer face of the walls in this part, the remains of the fosse stopping them on the one side, and a low wall of dry stone, alongside the road, on the other. The rock coming in flat sheets to the surface here, at different points, made the track more like a civilised highway; and, on the country side of it, gardens, within stone walls, brightened the route. Until recently the wide space between the olive-groves, farther north, and the city wall, was a naked stretch of broken rock, or a mere waste, thinly sprinkled with grass, which withered into hay after the brief spring. Of late years, however, the ground has fallen into the hands of Christians, and this, explain it how we may, accounts for the change, which is just as marked, in similar cases, everywhere in Palestine. Industry—the industry which always in this land characterises our religion—has made the wilderness blossom like the rose.* The popular name is used in these pages, as being better known than the new one, "the Dome of the Rock."

In early times this suburb was diligently utilised, as the remains of numerous cisterns and tanks sufficiently prove. Rich Jews had their fine country-houses here, under the shadow of their olive and fig trees, and wealthy Roman officials and residents doubtless followed their example, for the shallow shares of the Eastern plough constantly turn up fragments of polished marble and cubes of mosaic flooring. It must, indeed, have been the same all round Jerusalem, for at two different places on the Mount of Olives, where excavations have recently been made, the mosaic floors of baths and rooms have been laid bare, with portions of the columns and delicately finished walls of the mansions to which they belonged. Even now, those who can afford to do it leave the city in the hot months, to enjoy the coolness of the orchards outside, and no foreign resident then lives within the gates who can manage to get a house beyond them. That it has been always the same admits of no question; in fact, the whole upper Kedron valley was so overgrown with dwellings in the generation before the destruction of the city by Titus, that the Jews enclosed it within a new city wall. But it is idle to look for any notable remains of mansions, or of public buildings, in this part, any more than in the city itself, for every hostile force has in turn encamped on the north side of Jerusalem, and signalised its presence by widespread destruction. How much blood of the most widely separate races has this soil drunk in! Here perished thousands of Roman legionaries and auxiliaries drawn from half a world; here fell thousands of turbaned Saracens; here the Crusaders from the West sang their Frankish songs round their watch-fires; and since then, rocks and walls have echoed with the war-cries of the rough hordes of Central Asia, now ossified into the modern Turk. Such human associations, lighting up the darkness of the past with the memory of great events, give even so poor and commonplace a scene an interest which no mere natural beauty could excite.

At the north-west corner of the walls the ground sinks, southwards, to the Joppa Gate, and rises slowly towards the north-west. Going west, we reach the eastern slope of the Valley of Hinnom, from which we first set out in our circuit of the Holy City. The top of the valley is covered with an extensive Mahommedan cemetery, in the middle of which lies the broad, flat sweep of a shallow pool—the Birket-el-Mamilla—which is fed, in winter and spring, by the rains. It is from this that the water found in Hezekiah's Pool, in the city, flows, after the rains, through a small aqueduct which is open at different points. Crossing the sadly-neglected city of the dead, with its forest of head and foot stones, rising higher than the perpendicular slabs of our churchyards though generally narrower than these, one is surprised to reach, on the farther side, where a noble terebinth stands as outpost, an actually good piece of road leading to the Joppa Gate. As there is hardly such a thing as a made road in the whole country, from Dan to Beersheba, the existence of this short fragment seems inexplicable. It was the beneficial result of a very curious impulse to diligence. A widespread tradition affirmed that a great treasure had, in some past age, been buried not far from the Joppa Gate, and in order to secure this, some adventurers gave out that they wished to make the road, and got permission to do so. This apparently wild venture had, however, more justification in the East than it would have had with us, for it has often happened that in time of war, or to escape the extortion of pashas, men have hidden their money or jewels in the ground, and have died without revealing the place, so that their wealth has been lost to their heirs. It is, indeed, still common to do so in troublous times all over the East, the experiences of the Indian Mutiny of 1857 showing many examples, so that, as in the days of Christ, it is nothing unusual to find treasure hidden in a field (Matt 13:44).

The road from the terebinth-tree to the Joppa Gate is nearly level, opening on the wide vacant space sacred to loungers, to the stalls of small dealers, to asses waiting for hire, and to camels awaiting their burdens. This spot is generally very bustling, but especially so as the noon of Friday, the Mahommedan Sunday, approaches. Everyone then strives to get into the city, some on horses, asses, or camels, but the great majority on foot; young and old, men and women, rich and poor, in all the parti-coloured brightness of Oriental costume; for at twelve on the sacred day the gates are shut for an hour, and all the faithful think it right to hurry at that time to the Temple area, to pray before the Mosque of Omar, the holiest spot in the Mahommedan world, except the Kaabah at Mecca. Just so it must have been in ancient times, at nine each morning, and at three each afternoon, the hour of morning and evening prayer among the ancient Jews, when men "went up into the temple, to pray" (Luke 18:10). And just as, in our time, a Mahommedan stops and prays wherever the fixed moment for doing so may find him, his face towards Mecca, so the Jew, if unable to get to the Temple Hill before the horns of the Levites, now superseded by the cry of the muezzin, summoned him to devotion, turned his face towards the Holy of Holies, wherever he might be, and repeated the prescribed prayers, still heard in the synagogues, for, even then, forms of prayer were universally used by the Chosen People. The shutting of the city gate has its origin in a belief among the Moslem that the Christians would, at some time, take the Holy City during the great hour of prayer, if this precaution were neglected. Except the Joppa Gate, all the entrances to Jerusalem are, further, closed each night at sunset: a custom as old, at least, as the days of Joshua, for Rahab tells the King of Jericho that the two Jewish spies went out of the city "about the time of shutting of the gate, when it was dark" (Josh 2:5).

To realise the daily life of ancient Jerusalem, it is necessary to have before us not only the character of the streets, narrow, rough, and sometimes sunk in the middle at once for a gutter and a track for animals; the flat-roofed houses, with their balloon swellings to cover the stone arches of the rooms; the strange, dark-arched bazaars, like long narrow tunnels, with the booths of the traders on each side; the dress of the people; the character of the shops and the articles exposed for sale; but also the configuration of the ground, the source of the ancient water-supply, and much else.

At present, Jerusalem receives water, so essential in any country, so pressingly vital in a hot climate, from springs, wells, cisterns, pools, or reservoirs, and rivulets led by conduits into the city.

The Fountain of the Virgin, in the valley of the Kedron, or of Jehoshaphat, is the only true spring known to exist in Jerusalem, rising, it appears, from a living source beneath the great Temple vaults, and supplying the many fountains flowing from of old in the Temple area, and now sparkling round the Mosque of Omar, as well as maintaining the Fountain of the Virgin and the Pool of Siloam. Such a provision for ever fresh and limpid water was an essential in ancient worship, which in every religion, at least in warm climates, required copious supplies, both for ablution and to wash away the blood of the sacrifices. Without such a provision, indeed, the Temple could hardly have been raised on Mount Moriah. This local water-supply was also the very life of the city itself, in times of siege; Hezekiah taking the precaution, as we have seen (see p. 507), to bring its stream, by a subterranean tunnel from the Virgin's Fountain, which was carefully covered up, to a point within the walls to which access was at all times easy by a rock-cut staircase, a long gallery in the limestone, and a deep shaft. Milton speaks of it as the

a holy association which frequently occurs in the Sacred Writings. "There is a [perennial] river," chants the Psalmist, "the streams whereof make glad the city of God, the holy place of the tabernacle of the Most High" (Psa 46:4). "All my springs [my sources of delight] are in thee," says another of the sacred odes (Psa 87:7). At the Feast of Tabernacles a golden vessel, holding about a pint and a half, was filled daily from Siloam, and carried up to the Temple, amidst music and jubilation; so that the Rabbis say, "He who has not seen the joy of the water-drawing has never seen joy in his life." To this Isaiah alludes when he writes, "With joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of salvation" (Isa 12:3), thinking of the exiles from all lands resuming the solemnities of the Temple worship. In Ezekiel's vision, moreover, the sacred spring in the Temple rock is to swell into a mighty river, flowing eastward and westward into the glens of Hinnom and Kedron, and pouring down in fertilising streams to the Dead Sea, whose waters it is to turn to a living flood."——brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God":

On the west side of the wall of the old Temple enclosure there is a well which seems to tap an old watercourse discovered far below the ancient surface, on which, as we have seen, lay the huge stones of Robinson's Arch, thirty feet below the present one. The shaft, which is eighty feet deep, passes entirely through rubbish into the old rock-hewn conduit which runs somewhere to the south: a relic, perhaps, of the great works undertaken by Hezekiah, to supply the city with water (2 Chron 32:30). There may be a secret spring, now unknown, from which this stream flows, but part of it must come from the infiltration of rain. Permeating such a mass of foul rubbish, it is, however, unfit for drinking, though freely used for that purpose by the inhabitants.

The oldest cisterns in Jerusalem have been made by hewing out in the rock a bottle-shaped excavation at the bottom of a deep shaft. The surface-rains, and the percolation of water between the layers of rock, are sufficient to keep a small supply in these reservoirs even in the driest weather. Many of them must be of great antiquity, and it is quite possible that, among others, that in which Jeremiah was for a time confined (Jer 38:6) may still be in use. Besides these there are great subterranean tanks, from forty to sixty feet deep, hewn out of the soft limestone, which in Jerusalem underlies a harder bed of the same stone. The roofs of flat rock are thus strong enough to support themselves, where the tank is of moderate size, but where the space hollowed out is large, they are upheld by pillars of stone left by the hewers. Small holes through the upper hard limestone afforded access to the softer rock for these gigantic quarryings, but the labour of passing through such narrow apertures all the stones and chips removed must have been immense; nor is it too much to believe that the laborious plan of leaving the native rock as a roof shows that these tanks were dug before the use of the arch was known. In any case, they restore one feature of ancient Jerusalem.

A third form of cistern is that of a simple excavation in the rock, with an arch thrown over as a roof. This kind of reservoir, and the great rock tanks, were supplied in ancient times by aqueducts, but now depend on impure surface drainage. Still a fourth class of cisterns has been built, in modern times, in the rubbish over the ancient city, depending entirely, of course, on the rains. In the hands of Europeans, these, being carefully cemented and cleaned out each year, supply clear and good water, but those in the native houses are sadly different. In their keenness to gather all the water they can, the owners guide all that falls on the roof, or into the courtyard, to the cistern, and even collect it from the streets, which are habitually foul with every form of abomination. Hence, as the year advances, and the supply of water gets low, the hideous deposits in the bottom of the cisterns are stirred in drawing for daily wants, with a painful result, alike in the horrible mixture drunk by the population and in the smell given off. Fever, widely spread, inevitably follows, with numerous deaths, but no penalty seems to rouse the population to the most elementary regard for the commonest laws of cleanliness and health.

A city in itself so strangely unprovided with living springs could not, however, depend in its prosperous days simply on rain-water tanks or cisterns, or on the flow from the Virgin's Fountain; and, hence, large pools, fed by aqueducts, were added, outside the city and within. There are two, as we have seen, in the Valley of Hinnom; then there are the two pools of Siloam, and one north of the city; while traditions exist of others, now buried beneath rubbish, at three different points outside the walls. Within the walls were the so-called Pools of Hezekiah and Bethesda, now virtually useless. I have spoken of all except the pool north of the city, once the largest of the whole, but now almost filled up with soil washed into it by the rains. Situated at the head of the Kedron valley, it was admirably placed for catching the drainage of the uplands around it, the supply doubtless being brought into the city by a conduit, though no traces of one have yet been discovered.

Besides the well on the rubbish of the Tyropœon, there is only that known as Job's Well, at the lower side of the junction of the Kedron and Hinnom valleys. Connected with this is a tunnel, about six feet high, and from two to three feet wide, cut for more than eighteen hundred feet along the bed of the Hinnom Valley, to the west, at a depth of from seventy to ninety feet below the ground, and reached, at intervals, by flights of steps hewn in the rock. Such a work, dating from Bible times, shows the spirit and enterprise of the ancient population, but it also proves that the supply of water for the city has always been a pressing question. It must have been felt that the supply from all other sources was insufficient, or not always secure, else an undertaking so serious, at a level so greatly below the city, would not have been projected or carried out. Its object seems to have been to collect the water which flowed over the lower hard limestone strata after percolating through the softer beds above them.

To realise the vigorous life of the ancient Jewish citizens, as shown in their arrangements for a copious water-supply, we must, moreover, restore in fancy the provision they made for bringing it from a distance by aqueducts. Thus, from the Pools of Solomon, beyond the ridge on the south, the water was led along a conduit to Bethlehem; then carried under that town by a rock-hewn tunnel, and brought on in another conduit to the Temple area, into the huge reservoirs of which it emptied itself. The length of this gigantic work, in all its windings, is over thirteen miles (70,000 feet); an amazing triumph of engineering for the days of Solomon, or even of Hezekiah, during whose reign the first rude beginnings of Rome were founded. Indeed, when we trace it, as it entered and passed through Jerusalem, wonder is even heightened, so great are the difficulties overcome. Crossing the Valley of Hinnom a little above the Sultan's Pool, on pointed arches sunk to the level of the ground, it winds round the southern slope of Mount Zion, and enters the city at the west side of the old Tyropœon Valley, crossing which by the help of Wilson's Arch, it poured its waters into the Temple cisterns. Pipes from it supplied numerous fountains in the lower part of the city; and inside the Temple area there was an elaborate system of reservoirs, regulating the flow of the stream, and providing for the discharge of the waste into the great drain that ran down the east side of Mount Moriah to the Kedron valley.

This vast arrangement, however, has long ago been allowed to fall into disrepair, and though occasionally patched up, it is so rarely of any use that we may regard it as only a magnificent relic of "the glory of Solomon," whose greatness it vividly brings before us. For since a large supply of water must have been required at the Temple from the very first, it seems natural to accept the tradition that this huge aqueduct, with the pools from which it flows, and the amazing system of reservoirs under the Temple area into which its waters were poured, are a memorial of the achievements of the son of David.

But even this elaborate work is thrown into comparative shade by the "high-level" aqueduct which brought water at such a height as to supply the lofty streets of Mount Zion. South of Solomon's Pools, in a glen called Wady Byar, a flight of rock-hewn steps leads down to a chamber sixty feet below the ground at its upper end, and seventy at its lower. From this, a tunnel, from five to twenty-five feet high, stretches up the valley, away from Jerusalem, ending at a natural cleft in the rocks, from which water freely comes. From the lower end, a similar tunnel runs for nearly five miles through hard limestone, reaching day, at last, on the under side of a great dam of masonry which crosses the whole valley. Shafts, sixty to seventy feet deep, have been sunk in the rock, in the course of this long excavation, to facilitate the work; the dam being intended, as it seems, to keep back the surface-water till it soaked down to the channel opened for it beneath. About three furlongs below the dam, the channel, for this space running above ground, enters another tunnel a third of a mile in length, and a hundred and fifteen feet beneath the surface, and in some parts fourteen feet high. A masonry channel then winds round the hill, and, sinking below the ground again, crosses the valley at the head of which lie the Pools of Solomon, tapping the so-called "Sealed Fountain," and running along the side of the Valley of Urtas, till, near Bethlehem, it flowed, anciently, into a great tank. From this the water was carried, by means of an inverted syphon two miles long, over the valley in which is Rachel's tomb. This part of the great work is itself an extraordinary illustration of the skill of the ancient engineers who contrived it. The tube for the water is fifteen inches in diameter, the joints, which seem to have been ground or turned, being connected by an exceedingly hard cement, and set on a frame of blocks of stone, bedded in rubble masonry all round to the thickness of three feet. Unfortunately, we cannot trace the last section of the undertaking, which has been so completely destroyed that it is not known where the aqueduct finally entered Jerusalem. One fact, however, and that an astonishing one, has been discovered, viz., that it delivered water at a point twenty feet higher than the sill of the Joppa Gate, for it seems beyond question to have been the source from which the bronze statues in Herod's palace gardens, spoken of by Josephus as pouring water into the fountains, obtained their supply; and the palace stood on the top of Mount Zion. The glory of this great aqueduct appears due to the genius of Herod, and it must, therefore, in the days of our Lord, have been one of the recent wonders of his reign. Or was it, in part at least, due to Pontius Pilate? though his aqueduct may more probably have been one on an even greater scale, traces of which have recently been discovered, and by which water was brought from Hebron.

It is strange to think that a city distinguished by such gigantic provision for its well-being should have come into prominence at so late a period in the history of Israel. Till the close of David's reign at Hebron it was still in the hands of the Jebusites, who seem only to have occupied Mount Zion; Moriah being still left to the husbandman.* Ezekiel might say with truth, "Thy birth and thy nativity is of the land of Canaan; thy father was an Amorite, and thy mother a Hittite" (Eze 16:3,4,5). Here only, so far as we know, the original inhabitants of Palestine kept their footing in the hills for centuries after the Hebrew conquest, thanks to the almost impregnable position of their stronghold. Built on a summit of the central ridge of the country, it was isolated by deep valleys on all sides but the north, and hence, when once secured for Israel, it was the main guarantee of prolonged national life. Mount Zion rises no less than 2,550 feet above the sea, and is reached on all sides by a steady ascent, differing in this from Hebron, which, though the hills immediately north of it are nearly 1,000 feet higher,** itself lies in a valley, and is easy of approach from all sides. Jerusalem, on the contrary, is pre-eminently a mountain city, alike in its climate and in its military strength. As such, it is sung in inspired lyrics and imaged by prophets: "His foundation is on the holy mountains" (Psa 87:1). It is "the mountain of His holiness. Beautiful for situation, the joy of the whole earth, is Mount Zion" (Psa 48:1), "which cannot be removed, but abideth for ever" (Psa 125:1). It is God's "holy hill" (Psa 43:3). Jerusalem was "Ariel," "the Lion of God," "the city where David dwelt" (Isa 29:1,2); its rocky height, the lion's lair. "In Judah is God known; His name is great in Israel; in Salem also is His tent, and His dwelling place in Zion" (Psa 76:1,2). Cut off by the deep ravines around it from the possibility of wide extension, Jerusalem was noted in the earliest times for its compactness: it was "builded as a city that is compact together" (Psa 122:3), though the sloping sides of Hinnom and Olivet on the south and east, and the nearly level ground on the north of the city, permitted the growth of noble suburbs, as wealth increased. But even where these had been laid out in gardens round the mansions of the rich, the hills swelled up on every side as a natural defence, recalling the verse of the Psalm, "As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about His people from henceforth even for ever" (Psa 125:2).

As at present, so in the past, Jerusalem was defended by a circuit of walls. In recent years it has extended slightly beyond its fortifications, and they would be of no real value against artillery, if ever it should be, with infinite labour, dragged up from the coast plains. But in ancient times its walls were a vital necessity, and hence they constantly figure in the sacred writings. "Walk about Zion, and go round about her: tell the towers thereof. Mark ye well her bulwarks" (Psa 48:12,13). It was through the gates in these ramparts that Jehovah was to enter His city, when the Ark, as His emblem, was carried up in triumph through them by David, from the house of Obededom, and it may have been at this high event in the religious history of the nation that choirs of Levites sang, when the Palladium of Israel was thus slowly ascending to its mountain sanctuary, "Lift up your heads, O ye gates; and be ye lift up, ye ancient doors, and the King of Glory shall come in!" (Psa 24:7). And it is "out of Zion," His stronghold, that Jehovah will raise His thunder-like war-cry, and lead down the warriors of Israel against the heathen, in the day when He shall tread them down in the valley of Jehoshaphat as men tread the vintage grapes (Joel 3:12,16).* This is shown by the story of Araunah the Jebusite.

** 3,500 feet above sea-level. (Conder, Handbook, p. 210).

Among the different localities around the city, none is more worthy of a thoughtful visit than Bethany. Starting from the Joppa Gate with a friend, on two hired asses, we passed slowly round to the path that slants down from the Temple walls and the Mahommedan cemetery, to the bridge over the long-vanished Kedron. Crossing it, perhaps at the spot where our Lord often crossed it nearly nineteen hundred years ago, we passed in front of Gethsemane, southwards; our beasts keeping up their pattering walk, for it is always to be remembered that no one ever rides faster than a walking pace in a country utterly without roads, like Palestine. Gradually the track bent to the east, when we were opposite Ophel, on the other side of the valley, and climbed the south-west slope of the Mount of Olives, the lower part of which we had been skirting since leaving Gethsemane. There was no pretence of a road—simply a track worn by the traffic of ages, the rock cropping out at intervals in broken layers on the upper and under sides, and even on the path itself. The Mount of Offence lay on our right hand, rising from the hollow below. At the bend of the road, where we turned our faces almost east, the huge swell of Olivet rose in an easy slope 300 feet above us on the one hand, while, on the other, a little way off, was the Mount of Offence, bare and yellow, about a hundred feet lower: Bethany itself lies 400 feet lower than the top of the Mount of Olives, but our Lord no doubt, as a rule, when on foot, took the path which still goes over the summit, and is used habitually by the peasants from its being much shorter than the circuit taken by us as more easy for riding.

Passing the saddle between the Mount of Olives and the Mount of Offence, a small but delightful valley opened out on the lower side, adorned with fig, almond, and olive trees, the road continuing comparatively broad, though here and there roughly cut out of the slopes of rock.

As we neared Bethany, which is about two miles from Jerusalem by the winding road we had taken, the ground sank very slowly on the right, with outcrops of the flat limestone beds, showing themselves like steps amidst the thin grass, on which goats and sheep were feeding. Turning aside in search of rock tombs, I was greatly affected by finding several, a short way from the road, at just such a distance from Bethany as seemed to suit the Gospel account of the tomb of Lazarus. They were simply chambers, entered by going down two or three steps to a small level space before the face of the rock, which has been hewn perpendicularly, and then hollowed out to receive the dead. Entering the largest, which was the size of a very small low room, I found it thick with maidenhair fern; but the stone had long ago disappeared from the door, and there was no sign of burial. Indeed, if it were the tomb of Lazarus there would be no such sign. That it, or one of the others around, was that in which the brother of Martha and Mary had lain, appeared very probable, since there seemed to be no others between them and Bethany. The tomb, moreover, was outside the village (John 11:30,31), and it was on the Jerusalem side of it (John 11:18-20), Jesus having travelled by way of the Holy City, which would lie in His route in coming from the north. It may well be, therefore, that I stood on the very ground made sacred by His footsteps, and that this was the very spot that heard the words, "Lazarus! come forth!" Here, it may be, Martha and Mary, and the friends and neighbours who had come to console them, had seen the eyes of the Holy One wet with tears of love for His friend, and of grief over the reign of sin and death in so fair a world.

Bethany, "the house of poverty," or as it is now called, El Azariyeh, a corruption from "Lazarus,"* lies on one of the eastern spurs of the Mount of Olives. Its New Testament name may have risen from its being on the borders of the Wilderness of Judæa, though it is itself surrounded by gardens and orchards on a small scale; or, with more probability, from its having been a place frequented by lepers, who were popularly called "the poor"; the case of Simon the leper, who lived here, showing that it was a refuge for his unfortunate class (Mark 14:3), who were permitted by the rabbis to live in open villages like Bethany, though they could not remain within the gates of walled towns or cities.** Some have thought the word means "house of dates," but, as it seems to me, on insufficient grounds, for the root from which this derivation is sought means, at best, only "unripe dates,"*** and the palm is as unfruitful at Bethany as in other parts of the hill country of Judæa. Over the highest part of the village rise the fragments of a tower built by the famous Queen Millicent, wife of Fulke, fourth king of Jerusalem, to protect a cloister of black nuns which she founded in Bethany in AD 1138, beside the then existing church of St. Lazarus.

The village consists now of about forty flat-roofed mud hovels, unspeakably wretched in their squalor, and the population is exclusively Mahommedan. There is excellent water, which enables the poor creatures to grow numerous fig, olive, almond, and carob trees, in little orchards enclosed within loose walls, built of the stones cleared off the soil within, and running up and across the stony slope. Naturally, a "tomb of Lazarus" is shown, to which one descends by no fewer than twenty-six steps, only to find a poor chamber, which is very unlike a Jewish tomb. A church was built over the spot as early as the fifth century. The so-called site of the house of Martha and Mary is also pointed out; but as their home has been assigned to many different places at different times, no value whatever is to be set upon the claim. Nothing certain, in fact, is known, except that our Lord must have gone to and from Jericho by way of this village.* The "L" has been taken as an article by the Arabs.

** Delitzsch, Durch Krankheit, p. 60.

*** Buxtorff's Lex., p. 38.

In this sequestered spot, on the edge of the wilderness, our Saviour spent many peaceful hours. Surrounded and tended by deep and faithful love, He often refreshed Himself here, after His weary and disturbing conflicts with the pettiness and bigotry of the orthodox theologians of His people in Jerusalem. At home in the bosom of one of its families, and well known in the hamlets around, He could send His disciples before Him, without pre-intimation, to ask for the use of the ass on which He was about to ride into the city (Matt 21:2). Hither He came, every night, in the last week of His life, till He was betrayed, taking the footpath, one may suppose, over the top of Olivet, rather than the camel road round its south slope, by which I had ridden. He had no such true friends in Jerusalem as those on this spot. Bethany remains for ever sacred as the home of tender ideal friendship, realised in that of Martha and Mary for our Lord. One could linger, even amidst its present misery, to drink in the landscape around, on which the eyes of the Redeemer must so often have rested,—the blossoming trees round the huts; the green hollow, near at hand, below; the reddish-brown slopes of the Mount of Olives behind, and, on the south-east, as one looks over a large trace of olive-trees below, the table-land of the Moab hills, pink and grey, beyond the Dead Sea; the rough, barren, brown waste of slopes and peaks of the wilderness of Judæa; the flat-topped cone of the Frank Mountain, and the pink hills of Quarantania, far down in the depression towards Jericho.

Up from that depth of nearly 3,000 feet below Bethany joyous multitudes of Galilean pilgrims, journeying to the Feast, came, and accompanied the Saviour on His last ascent to Jerusalem. Joy filled all hearts but His, for not only was the Passover at hand, but as Galileans they were proud of "Jesus the prophet," from their own Galilean town of Nazareth, and were ready to hail Him as the long-expected Messiah. On His side, it was becoming that now, on the eve of His self-sacrifice, He should solemnly assume the headship of the new kingdom of God, soon to be founded by His atoning death, and by a formal act, clearly understood when men came to reflect, claim the mysterious dignity of the Christ, or Anointed, of God. From Bethany, therefore, with its heights of wild uplands over it and the long ridge of Olivet shutting out the troubles of the tumultuous city on its western side, He set forth, on the opening morning of His Passion Week, after resting the night before in the peaceful cottage of His friends. The road He took was undoubtedly that by which I had come; the creature He rod, an ass, the symbol of early Jewish royalty, and then even more the usual creature for riding than now, though it is still used by all ranks. "Two streams of people met as He advanced.* The one poured out from the city, and as they came through the gardens, whose clusters of palms rose on the south-eastern corner of Olivet, they cut down the long branches, as was their wont at the Feast of Tabernacles, and moved upwards towards Bethany, with loud shouts of welcome. From Bethany streamed forth the crowds who had assembled there on the previous night, and who came testifying to the great event at the sepulchre of Lazarus (John 12:7). The road soon loses sight of Bethany. It is now a rough but still broad and well-defined mountain track, winding over rock and loose stones; a steep declivity below, on the left; the sloping shoulder of Olivet above it, on the right; fig-trees, below and above, here and there growing out of the rocky soil. Along the road the multitudes threw down the branches which they cut as they went along, or spread out a rude matting, formed of the palm branches they had already cut as they came out. The larger portion—those, perhaps, who escorted Him from Bethany—unwrapped their loose cloaks from their shoulders, and stretched them along the rough path, to form a momentary carpet as He approached (Matt 21:8). The two streams met midway. Half of the vast mass, turning round, preceded; the other half followed (Mark 11:8). Gradually, the long procession swept up and over the ridge, where first begins 'the descent of the Mount of Olives' towards Jerusalem. At this point the first view is caught of the south-eastern corner of the city. The Temple and the more northern portions are hid by the slope of Olivet on the right; what is seen is only Mount Zion, now, for the most part, a rough field, crowned with the Mosque of David, and the angle of the western walls, but then covered with houses to its base, surmounted by the Castle of Herod, on the supposed site of the Palace of David, from which that portion of Jerusalem, emphatically 'The City of David,' derived its name. It was at this precise point, 'as He drew near, at the descent of the Mount of Olives' (Luke 19:37) (may it not have been from the sight thus opening upon them?) that the shout of triumph burst forth from the multitude, 'Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is He that cometh in the name of the Lord. Blessed is the Kingdom that cometh of our father David. Hosanna—peace—glory in the highest' (Matt 21:9; Mark 11:9; John 12:13; Luke 19:37). There was a pause, as the shout rang through the long defile; and as the Pharisees who stood by in the crowd complained (Luke 19:39), He pointed to the stones which, strewn beneath their feet, would immediately 'cry out' if 'these held their peace.'

"Again the procession advanced. The road descends a slight declivity, and the glimpse of the city is again withdrawn behind the intervening ridge of Olivet. A few moments, and the path mounts again, it climbs a rugged ascent, it reaches a ledge of smooth rock, and, in an instant, the whole city bursts into view. As now the Mosque of El Aksa rises, like a ghost, from the earth, before the traveller stands on the ledge, so then must have risen the Temple tower; as now the vast enclosure of the Mussulman sanctuary, so then must have spread the Temple courts; as now the grey city on its broken hills, so then the magnificent city, with its background—long since vanished away—of gardens and suburbs on the western plateau behind. Immediately below was the valley of the Kedron, here seen in its greatest depth, as it joins the Valley of Hinnom, and thus giving full effect to the great peculiarity of Jerusalem, seen only on its eastern side—its situation as of a city rising out of a deep abyss. It is hardly possible to doubt that this rise and turn of the road—this rocky ledge—was the exact point where the multitude paused again, and He, when He beheld the city, wept over it."* I quote the exquisite description of Dean Stanley in Sinai and Palestine, p. 187.

Chapter 25 | Contents | Chapter 27

Philologos | Bible Prophecy Research | The BPR Reference Guide | Jewish Calendar | About Us