by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

Philologos Religious Online Books

Philologos.org

Chapter 24 | Contents | Chapter 26

Cunningham Geikie D.D.

With a Map of Palestine and Original Illustrations by H. A. Harper

Special Edition

(1887)

From the Virgin's Fountain towards the north the valley contracts still more, and the sides become steeper. On the right hand especially, as you advance, the hill is very wild; sheets of rock, rough outcrops of the horizontal strata, and bare walls of limestone, making the path as wild as that of a Highland glen. Indeed, steps have been cut in more than one place, to help man and beast in their laborious progress. In this, the narrowest part of the Valley of Jehoshaphat, the Jews of to-day have the cemetery dearest of all to their race, for here the dead lie, under the shadow of the Temple Hill, in the sacred ground on which the great Judgment will, in their opinion, be held. Numberless flat stones mark the graves on both sides of the waterless bed of the Kedron, especially on the eastern. Above them, a little to the north, the eye catches a succession of funeral monuments, which offer, in their imposing size and style, a strong contrast to the humble stones that pave the side of the hill close at hand. They are four in number, and have all been cut out of the rock, which remains in its roughness on each side of them. The first is that of Zechariah, a miniature temple about eighteen feet square, with two Ionic pillars and two half-pillars on each side, and a square pillar at each corner. Over these are a moulded architrave and a cornice, the pattern of which is purely Assyrian. From these there rises a pyramidal top—the whole monument being hewn, in one great mass, out of the rocky ledge, without any apparent entrance, though one may possibly be hidden under the rubbish accumulated during the course of ages in the broad passage which runs round the tomb. The whole structure is about thirty feet high. From the Assyrian cornice it might be thought to be as old as the early Jewish kings, but traces of Roman influence in the volutes and in the moulding beneath make it probable that it is not older than the second century before Christ, who doubtless often passed by it.

The tradition of the Jews, current in our Lord's day, associated with this monument the Prophet Zechariah, who was stoned, by command of King Joash, "in the court of the house of the Lord" (2 Chron 24:20-22); and it may well be that Christ was looking down upon it from the Temple courts close above, on the opposite side of the valley, when He addressed the Pharisees, with whom He had been disputing, in the bitter words: "Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! because ye build the tombs of the prophets, and garnish the sepulchres of the righteous. Wherefore ye be witnesses unto yourselves that ye are the children of them which killed the prophets" (Matt 23:29-31). I noticed square holes in the rock on the south side, probably the sockets in which the masons rested the beams of the scaffold while they were cutting out the tomb.

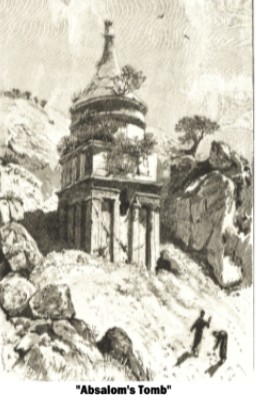

The so-called Tomb of Absalom is the most stately of the four monuments. It is forty-seven feet high, and nearly twenty feet square; hewn, like that of Zechariah, out of the rock, and separated from it, at the sides, by a passage eight or nine feet broad, but not detached from the hill at the back. The natural rock has, in fact, simply been hewn away on three sides, to form the body of it; but the upper part, which is in the form of a low spire, with a top like an opening flower, is built of large stones. The solid body is about

twenty feet high, so that the upper part rises twenty-seven feet over it, but the height of the whole must have been originally greater, as there is much rubbish lying round the base, and covering the entrance. The sides are ornamented with Ionic pillars, over which is a Doric frieze and architrave. Wild plants grow out of the chinks between the stones of the spire, and on the base from which it springs, and a chaos of stones lies on the ground below. A hole in the north side, large enough to creep through, is the only way to get inside, but there is now nothing to be seen, except an empty space about eight feet square, with tenantless shelf-graves on two sides, cut in the rock. In the Second Book of Samuel we read that "Absalom, in his lifetime, had taken and reared up for himself a pillar which is in the king's dale, for he said, I have no son to keep my name in remembrance; and he called the pillar after his own name; and it is called, to this day, Absalom's place."* The Grecian ornaments on the present monument show, however, that it could not, in its present form, have come down from a period so early; but the solid base may have been more complete long ago, and the adornments may have been added to it later.

The so-called Tomb of Absalom is the most stately of the four monuments. It is forty-seven feet high, and nearly twenty feet square; hewn, like that of Zechariah, out of the rock, and separated from it, at the sides, by a passage eight or nine feet broad, but not detached from the hill at the back. The natural rock has, in fact, simply been hewn away on three sides, to form the body of it; but the upper part, which is in the form of a low spire, with a top like an opening flower, is built of large stones. The solid body is about

twenty feet high, so that the upper part rises twenty-seven feet over it, but the height of the whole must have been originally greater, as there is much rubbish lying round the base, and covering the entrance. The sides are ornamented with Ionic pillars, over which is a Doric frieze and architrave. Wild plants grow out of the chinks between the stones of the spire, and on the base from which it springs, and a chaos of stones lies on the ground below. A hole in the north side, large enough to creep through, is the only way to get inside, but there is now nothing to be seen, except an empty space about eight feet square, with tenantless shelf-graves on two sides, cut in the rock. In the Second Book of Samuel we read that "Absalom, in his lifetime, had taken and reared up for himself a pillar which is in the king's dale, for he said, I have no son to keep my name in remembrance; and he called the pillar after his own name; and it is called, to this day, Absalom's place."* The Grecian ornaments on the present monument show, however, that it could not, in its present form, have come down from a period so early; but the solid base may have been more complete long ago, and the adornments may have been added to it later.

A recent traveller, standing on the Temple wall above, on the other side of the ravine, saw two children throw stones at the memorial, and heard them utter curses as they did so; and it is to this custom, followed for ages, that much of the rubbish at the base is due. The Rabbis from early ages have enjoined that "if any one in Jerusalem has a disobedient child, he shall take him out to the Valley of Jehoshaphat, to Absalom's Monument, and force him, by words or stripes, to hurl stones at it, and to curse Absalom; meanwhile telling him the life and fate of that rebellious son." To heap stones over the graves of the unworthy, or on a spot infamous for some wicked deed, has been a Jewish custom in all ages. On the way to Gaza I passed a cairn thus raised on the spot where a murder had been committed some time before, and I saw one at Damascus of enormous size, every passer-by, for generations, having added a stone. So, the hebrews "raised a great heap of stones unto this day," over Achan, near Ai (Josh 7:26), and this was done also over the body of the King of Ai, "at the entering of the gate," when Joshua took the city (Josh 8:29). Thus, also, when Absalom had been killed in the wood by Joab, they took his corpse and "cast him into a great pit in the wood, and laid a very great heap of stones upon him" (2 Sam 18:17).* 2 Sam 18:18. For "place," read "monument."

The traditional Tomb of Jehoshaphat, close to that of Absalom, is a portal cut in the rock, leading down to a subterranean tomb, with a number of chambers; how old no one can tell. Exactly opposite the south-east corner of the Temple enclosure is "the Grotto of St. James," with a Doric front, leading to an extensive series of sepulchral chambers, spreading far into the body of the hill. The name of the family—the Beni Hezir—is on the facade, in early Hebrew characters; but the structure is connected with St. James by a monkish tradition that he lay concealed in it during the interval between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, though this venerable association has not saved it in later times from being used as a fold for sheep and goats.

Near Absalom's Pillar, a small stone bridge, of one low arch, leads over the narrow ravine to the Temple Hill. A rough channel has been torn in the valley beneath it by the rain-floods of past times, but of a channel beyond there are no signs a short distance above or below it, the upper reaches of the valley being walled across, here and there, with loose stones to form grain-plots. The Kedron used in olden days to flow here, but there is no stream now, even after the heaviest rain, the loose rubbish which has poured from the ruin of the walls and buildings of the city above, during many sieges, having so filled the old bed that any water there may be now percolates through the soil and disappears. At least seventy-five feet of such wreckage lies over the bottom of the upper part of the valley and on the slopes of the Temple Hill leading down to it; but even this is far less than what has been tumbled into the Tyropœon, on the other side of the hill. There 100 feet of rubbish hides the stones of the old Temple walls, thrown into it after the destruction of the Temple by Nebuchadnezzar's soldiery.

In the steep, rocky part of the Kedron valley, near the tombs of the Jewish cemetery, there are no olive-trees to be seen, but they begin to be numerous on the upper side of the little bridge, and there are some almond-trees on Mount Moriah. The walls of the Temple enclosure proudly crown the eastern side of the hill, their colossal size still exciting the same astonishment as it once roused in the disciples, when they called aloud, "Master, see what manner of stones and what buildings!" (Mark 13:1). On the bridge, or near it, some lepers were standing or sitting on the ground, begging; hideous in their looks and their poverty. A water-seller or two, also, were standing at the wall, offering their doubtful beverage to passers-by. The bridge is the one passage from the east side of Jerusalem to Mount Olivet and Siloam, so that there are always people passing. Sheep graze on the wretched growth near the tombs; their guardians, picturesque in their poverty, resting in some shady spot near. Asses with burdens of all kinds jog along over the sheets of rock, their drivers walking quietly behind the last one. The creatures never think of running, and there is only one possible path, so that it is not necessary to lead them. A church, known as the Chapel of the Tomb of the Virgin, stands within white walls on the eastern side of the bridge, and a short way down from it is a garden, to name which is enough: Gethsemane—"the Oil Press"; the spot to which, or to some place near, our Lord betook Himself after the institution of the Last Supper on the night of His betrayal. Here, in the shadow of the Trees of Peace, amidst stillness, loneliness, and darkness, except for the light of the Passover moon, His soul was troubled even unto death. Here He endured His more than mortal agony, till calmness returned with the holy submission that once and again rose from His inmost heart—"Father, not My will, but Thine, be done!" No Christian can visit the spot without being deeply affected. Numerous olive-trees still grow on the slopes and in the hollow, and of these the Franciscans have enclosed seven within a high wall, in the belief that they are the very trees under which our Saviour prayed. But within a few decades after He had been crucified, the Roman general Titus ordered all the trees, in every part around Jerusalem, to be cut down; and when, in later times, others had taken their places, there is little doubt that they, too, perished, to supply the timber or fuel needed for some of the many sieges Jerusalem has borne since. It is, hence, impossible to tell the exact site of the ancient Gethsemane, nor is it essential that we should. Superstition may crave to note the very scene of a sacred event, but the vagueness of doubt as to the precise spot only heightens the emotion of a healthy mind, by leaving the imagination free.

That the Betrayal, with all its antecedent agony, took place somewhere near the small Kedron bridge, there can, however, be no doubt, for the flight of steps which formerly led from St. Stephen's Gate to the valley was the natural exit from the city in Christ's day. These, however, are now buried beneath 100 feet of rubbish, and no one would venture, in the night, down the rocky descent which begins a short distance below the bridge. While, moreover, the present olive-trees cannot be those beneath which our Lord kneeled, the fact that such trees still grow on the spot shows that it was just the place for the garden of our Saviour's time to have been, though it may have lain above the bridge instead of below it. The spot now called Gethsemane seems to have been fixed upon during the visit of the Empress Helena to Jerusalem, in AD 326, when the places of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection were supposed to have been identified. But 300 years is a long interval; as long, indeed, as the period from Queen Elizabeth's day till now, and any identification made after such a time must be doubtful. Yet the site that can boast recognition of nearly 1,600 years has deep claims on our respect, though other similar enclosures exist near it, and other olive-trees equally ancient are seen in them. At one time the garden was larger than at present, and contained several churches and chapels. The scene of the arrest of Christ was pointed out, in the Middle Ages, in what is now called "the Chapel of the Sweat," and the traditions respecting other spots connected with the last hours of our Lord have also varied, but only within narrow limits, for since the fourth century, at all events, the garden has always remained the same.

The wall of Gethsemane, facing Jerusalem, is continuous, the entrance to the garden being by a small door at the eastern, or Mount of Olives, side. Immediately outside this you are shown the spot where Peter, James, and John, are said to have slept during the Agony; and the fragment of a pillar, a few paces to the south, but still outside the garden, is pointed to as the place where Judas betrayed his Master with a kiss. The garden itself is an irregular square, 160 feet long, and ten feet narrower, divided into flower-beds and protected by hedges; altogether, so artificial, trim, and modern, that one is staggered by the difference between the reality and what might be expected. The seven olive-trees are evidently very old; their trunks, in some cases, burst from age, and shored up with stones, the branches growing like thin rods from the massive stems, one of which measures nineteen feet in circumference. Roses, pinks, and other flowers, blossom in the borders of the enclosure, and here also are some young olive-trees and cypresses. Olive oil from the trees of the garden is sold at a high price, and rosaries made from stones of the olives are in great request. I wish, however, there were less of art and more of nature in such a spot, for it is easier to abandon one's self to the tender memories of Gethsemane under the olives on the slope outside the wall, than amidst the neat walks and edgings and flower-beds within it.

The Chapel of the Tomb of the Virgin, over the traditional spot where the Mother of our Lord was buried by the Apostles, is about fifty steps east of the little bridge, and is mostly underground. Three flights of steps lead down to the space in front of it, so that nothing is seen above ground but the porch. But even after you have gone down the three flights of stairs, you are only at the entrance to the church, amidst marble pillars, flying buttresses, and Pointed arches. Forty-seven additional marble steps, descending in a broad flight nineteen feet wide, lead down a further depth of thirty-five feet, and here you are surrounded by monkish sites and sacred spots. The whole place is, in fact, two distinct natural caves, enlarged and turned to their present uses with infinite care; curious from the locality, and perhaps no less so as an illustration of the length to which superstition may go in destroying the true sacredness of a spiritual religion like Christianity. Far below the ground you find a church thirty-one yards long and nearly seven wide, lighted by many lamps, and are shown the tomb of the father and mother of the Virgin, and that of Joseph and the Virgin herself; and as if this were not enough, a long subterranean gallery leads, down six steps more, to a cave eighteen yards long, half as broad, and about twelve feet high, which you are told is "the Cavern of the Agony"! Of course, sacred places so august could not be left in the hands of any single communion, so that portions belong respectively to the Greeks, Armenians, Abyssinians, and Mahommedans. Yet the whole is very interesting, for the beautiful architecture of marble steps, pillars, arches, and vaulted roof, owes its present perfection to the beneficence of Queen Melesind or Millicent, in the twelfth century, and is perhaps the most perfectly preserved specimen of the work of the Crusading church-builders now extant in Palestine.

Gethsemane and the Chapel of the Tomb of the Virgin are at the foot of the Mount of Olives, which can easily be ascended from them, for its summit lies only about 350 feet higher, and is reached by a gentle incline, up which one may walk pleasantly in about a quarter of an hour. A pilgrim was reverently kissing the rocks behind Gethsemane; flocks of black goats and white sheep nibbled the hill plants or scanty grass; the rubbish-slopes of Mount Moriah rose, sprinkled with bushes and a few fruit-trees, making them look greener than the comparatively barren and yellow surface of the Mount of Olives. Yet the olives scattered in clumps or singly over all the ascent, made it easy enough to realise how the hill got its name from being once covered with their white-green foliage, refreshing the eye, and softening the pale yellow of the soil.

The whole slope of Olivet is seamed with loose stone walls, dividing the property of different owners, and is partly ploughed and sown, but there is a path leading unobstructedly from behind Gethsemane to the top of the hill. Many of the enclosures are carefully banked into terraces from which the stones have been laboriously gathered into heaps, or used to heighten and strengthen the walls; and when I visited the place there were some orchards in which olive, pomegranate, fig, almond, and other trees, showed their fresh spring leaves or swelling buds. Nor is any part of the slope without its flowers: anemones and other blossoms were springing even in the clefts of the rocks.

There may be said to be three summits: the centre one slightly higher than the others, like a low head between two shoulders. This middle height is covered on the top with buildings, among which is the Church of the Ascension, though it is certain that Christ did not ascend from the summit of Olivet, for it is expressly said that He led His disciples "out, as far as to Bethany," and, moreover, the top of the hill was covered with buildings in Christ's day. From a very early date, however, it has been supposed to be the scene of the great event, for Constantine built upon it a church without a roof, to make the spot. Since then, one church has succeeded another, the one before the present dating from AD 1130, when it was built by the Crusaders; but this in turn having become ruinous, it was rebuilt in 1834, after the old plan. It stands in a large walled space entered by a fine gate, but is itself very small, measuring only twenty feet in diameter; a small dome over a space in the centre marking, it is asserted, the exact spot from which our Lord ascended. This specially holy spot belongs to the Mahommedans, who show a mark in the rock which, they tell you, is a footprint of Christ. Christians have to content themselves with having mass in the chapel on some of the great Church feasts. The church stands in the centre of the enclosure.

There may be said to be three summits: the centre one slightly higher than the others, like a low head between two shoulders. This middle height is covered on the top with buildings, among which is the Church of the Ascension, though it is certain that Christ did not ascend from the summit of Olivet, for it is expressly said that He led His disciples "out, as far as to Bethany," and, moreover, the top of the hill was covered with buildings in Christ's day. From a very early date, however, it has been supposed to be the scene of the great event, for Constantine built upon it a church without a roof, to make the spot. Since then, one church has succeeded another, the one before the present dating from AD 1130, when it was built by the Crusaders; but this in turn having become ruinous, it was rebuilt in 1834, after the old plan. It stands in a large walled space entered by a fine gate, but is itself very small, measuring only twenty feet in diameter; a small dome over a space in the centre marking, it is asserted, the exact spot from which our Lord ascended. This specially holy spot belongs to the Mahommedans, who show a mark in the rock which, they tell you, is a footprint of Christ. Christians have to content themselves with having mass in the chapel on some of the great Church feasts. The church stands in the centre of the enclosure.

The minaret of a dervish monastery, just outside the wall, on the left, in front of a miserable village, affords the finest view to be had around Jerusalem. No one hindered my ascending it by the stairs inside, though some children and men watched me, that I might not leave without an effort on their part to get bakshish. On the west lay Jerusalem, 200 feet below the ground I had left. The valley of the Kedron was at my feet, and above it the great Temple area, now sacred to the Aksa Mosque, and to that of Omar, which rose glittering in its splendour in the bright sunshine. Beyond, the city stretched out in three directions; slender minarets shooting up from amidst the hundreds of flat roofs which reached away at every possible level, and were varied by the low domes swelling up from each of them over the stone arch of the chamber beneath; the great dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the towers of the citadel standing proudly aloft over all. The high city walls, yellow and worn with age, showed many a green field inside the battlements.

Turning to the north, a rich olive-garden spread away from before the Damascus Gate, and the long slope of Nebi Samwil or Mizpeh closed the view, in the distance, like a queen among the hills around, with its commanding height of nearly 3,000 feet (2,935 feet) above the sea-level. Close at hand was the upper part of the Kedron valley beautiful with spring flowers; and overlooking Jerusalem rose Mount Scopus, once the head-quarters of Titus, when its sides were covered with the tents of his legionaries. On the south were the flat-topped cone of the Frank Mountain, where Herod the Great was buried; the wilderness hills of Judah; the heights of Tekoa and of Bethlehem, which itself is out of sight, though the neighbouring villages, clinging to richly-wooded slopes, are visible; the hills bounding the Plain of Rephaim or the Giants; and the Monastery of Mar Elias, looking across from its eminence towards Jerusalem. But the most striking view is towards the east. It is impossible to realise, till one has seen it, how the landscape sinks, down, and ever down, from beyond the Mount of Olives to the valley of the Jordan. It is only about thirteen miles, in a straight line, to the Dead Sea, but in that distance the hills fall in gigantic steps till the blue waters are actually 3,900 feet below the spot on which I stood. It seemed incredible that they should be even so far off, for the pure transparent air confounds all idea of distance, and one could only correct the deception of the senses by remembering that these waters could be reached only after a seven hours' ride through many gloomy, deep-cut ravines, and fearfully desolate waterless heights and hills, over which even the foot of a Bedouin seldom passes. Nor are the 3,900 feet the limit of this unique depression of the earth's surface, for the Dead Sea is itself, in some places, 1,300 feet deep, so that the bottom of the chasm in which it lies is 5,200 feet below the top of Mount Olivet.

The colour of the hills adds to the effect. Dull greenish-grey till they reach nearly to the Jordan valley, they are then stopped, at right angles, by a range of flat-topped hills of mingled pink, yellow, and white. The hills of Judah, on the right, looked like crumpled waves of light-brown paper, more or less strewn with dark sand—the ideal of a wilderness; those before me were cultivated in the nearer valleys and on the slopes beyond. Behind the pinkish hills on which I looked down lay the ruins of Jericho and the famous circle of the Jordan, beneath the mud-slant of which lies the wreck of the Cities of the Plain; then came the deep-blue waters of the Dead Sea, and beyond them the pink, flat-topped mountains of Moab, rising as high as my standing-place. To the far south of these mountains, on a small eminence, lay the town of Kerak, once the capital of King Mesha, the Kir Haresh, Kir Hareseth, Kir Heres, and Kir Moab of the prophets (Isa 15:1, 16:11; Jer 48:31,36; Isa 16:7; 2 Kings 3:25). There, when Israel pressed their siege against his capital, King Mesha offered up on the brick city walls to the national god, Chemosh, his eldest son, "who should have reigned in his stead." Nearer at hand, in the same range, but hidden from view, frowning over a wild gorge below, lay the black walls of Machærus, within which John the Baptist pined in the dungeons of Herod Antipas, till the sword of "the fox's" headsman set his great soul free to rise to a foremost place in heaven. And at the mouth of that deep chasm, amongst rushing waters, veiled by oleanders, lay Callirhoe, with its famous hot springs, where Herod the Great nearly died when carried over to try the baths, and whence he had to be got back as best might be to Jericho, to breathe his last there a few days after. South of this lay the wide opening in the hills which marked the entrance of the Arnon into the Dead Sea, once the northern boundary of Moab (Num 21:13,26; Deut 3:8; Josh 12:1; Isa 16:2; Jer 18:20). To the north, across the Jordan, rose the mountains of Gilead, from Gerasa, beyond the Jabbok, where Jacob divided his herds and flocks, and sent them forward in separate droves, for fear of his brother Esau, and near which, at Peniel, he wrestled with the angel through a long night (Gen 32:16,24). Then, sweeping southwards, still beyond the Jordan, which flowed, unseen, in its deep sunken bed, one saw Baal Peor, where the Israelites sinned, and Mount Pisgah, whence Moses looked over the Promised Land he was not to enter, and Mount Nebo, where he died, though we know not what special peaks to associate with these memories. Where the Jordan valley opens, the course of the stream was shown by a winding green line threading a white border of silt and stones. At its broadest part, before reaching the Dead Sea, now lying so peacefully and in such surpassing beauty below me, the valley becomes a wide plain, green with spring grain and groves of fruit-trees, including palms. Such a view, so rich in hallowed associations, can be seen only in Palestine.

The Mount of Olives has been holy ground from the almost immemorial past. On its top David was "worshipping God" on his flight from Jerusalem to escape from Absalom's revolt, his eyes in tears, his head covered with his mantle, his feet bare, when Hushai, his friend, came, as if in answer to the prayers even then just rising, and undertook to return to the city and undo the counsel of Ahithophel (2 Sam 15:32). In Ezekiel's vision the glory of the Lord went up from the midst of the city and stood upon the mountain which is on the east side of the city—that is, on the Mount of Olives (Eze 11:23); it was on it, also, that Zechariah, in spirit, saw the Lord standing to hold judgment on His enemies; and it was this hill which His almighty power was one day to cleave "toward the east and toward the west," so that there would be "a very great valley" through which His people might have a broad path for flight (Zech 14:4 ff). It was while standing, or resting, on this hill that our Lord foretold the doom impending over Jerusalem (Matt 24:2; Mark 13:2; Luke 19:41); and it was from some part of it, near Bethany, that He ascended to heaven (Acts 1:9,12; Luke 24:50).

Making my way down again to Gethsemane, I crossed the little stone bridge over what represents the old channel of the Kedron, when that torrent was a reality, and rode up a path to the St. Stephen's Gate. From this point the comparatively level ground, extending along the eastern wall of the Temple enclosure, is a Mahommedan cemetery; each grave with some superstructure, necessary from the shallowness of the resting-place beneath. Over the richer dead a parallelogram of squared stones, or of stone or brick plastered over, but in every case with head and foot stones jutting out high above the rest, is the commonest form. The poorer dead have over them simply a half-circle of plastered bricks or small stones, the length of the grave, with the two stones rising at the head and feet. No care whatever is taken of the ground, over which man and beast walk at pleasure, nor does there seem to be any thought of keeping the graves in repair. Coarse herbage, weeds, and great bunches of broad-leaved plants of the lily kind, grow where they like amidst the utterly neglected dead.

On the north side of Jerusalem, the natural rock, cut into perpendicular scarps of greater or less height, forms at different points the foundation of the city walls. At other parts, the rock juts out below the walls in its natural roughness, lifting up the weather-stained, many-angled masonry into the most picturesque outline. On most of the northern aspects of the walls, cultivated strips run, here and there, between them and the road, the counterparts of similar belts and patches along their inner side. Near the Damascus Gate the remains of an old moat heighten the effect of the walls, while a mound of rubbish on the other side of the road, thrown down during the building of the Austrian Hospice, has helped to confuse the ancient appearance of the spot. About 100 yards east of the gate, in the rock, nineteen feet below the wall, you come on the entrance to the so-called "Cotton Grotto," which is in reality an extensive quarry, of great antiquity, stretching far below the houses of the city. The opening was discovered in 1852, but is so filled with masses of rubbish that it can only be entered by stooping very low, or by going in backwards and letting one's self down some five feet to the floor of the quarry. From this black mouth the gulf stretches away, at first over a great bed of earth from the outside, then over rough stones. The roof, about thirty feet high, is coarsely hewn out, and the ground underfoot, as you go on for 645 feet, in a south-easterly direction, under the houses and lanes of Bezetha, is littered with great mounds of chips, or heaped with masses of stone, in part fallen from the roof. The excavations slope pretty steeply from the very entrance to a depth of 100 feet at their far end. Some boys were playing in the road as I approached, and clamoured to guide me, hurrying away to buy candles and matches with money I gave them on accepting their service. At one place, deep in the heart of the quarry, was a small, round basin, with some water in it; the hollow worn by the slow dripping of some broken cistern in the town overhead. The lime dissolved by the water hung here, and at some other parts, in long stalactites from the roof, and rose in white mounds of stalagmite from the ground.

It was hard work to follow my active guides, who often gave me less light than was pleasant, as they tripped lightly over the masons' rubbish, lying just as the workmen had left it. But a word brought them back, and they were careful to hold their candles down at specially difficult places, where huge stones, cut thousands of years ago, but never used, lay in dire confusion. The roof was supported, at intervals, by very rough masses of rock. This great excavation dates from no one can tell what period, and lay forgotten and unknown for centuries. You still see clearly the size and form of the masons' and hewers' tools, for the marks of the chisel and the pick are as fresh as if the quarriers and the stone-cutters had just left their work. They appear to have been associated in gangs of five or six; each man making a cutting in the rock perpendicularly, four inches broad, till he had reached the required depth; after which, wedges of timber, driven in and wetted, forced off the mass of stone by their swelling. It is touching to notice that some blocks have been only half cut away from their bed, like the great stone at the quarry of Baalbek, or the enormous obelisk in the granite quarries of Assouan.

In all probability it was from these quarries that Solomon obtained the huge stones which we see built into what remains of the Temple walls, and of its area. They were evidently dressed before being removed, so as to be ready to be laid at once, one on another, for otherwise it would be impossible to account for the vast quantities of chips and fragments on the bottom of the quarry. We can thus understand the words of the sacred writer who tells us that "the house, when it was in building, was built of stone made ready at the quarry; and there was neither hammer, nor axe, nor any tool of iron heard in the house while it was in building" (1 Kings 6:7). But what can we think of a man who could doom his wretched subjects—rendering, we may assume, forced, unpaid labour in this case as in his other great undertakings—to toil in the darkness and dampness of these subterranean wastes, not only in cutting out the stone from the rock, but in squaring and finishing it, for a temple to Jehovah? How many lives must have been worn out in these gloomy abysses! Shards of pottery—perhaps the vessels in which they once put their humble meals—with fragments of charcoal, and of long-decayed wood, and the skeletons of men and animals, were found in the quarries when they were re-discovered, some thirty-five years ago. Niches in the rock, and spots black with the smoke of lamps or candles, show where, thousands of years ago, a feeble light shone out on the pinched features and worn frames of the lonely toilers, the equals, after a few years, of Solomon in the dusty commonwealth of death, in spite of all his glory while he lived, and of all their sweat and misery at his hand.

Opposite this stupendous quarry, but a little to the east, there is a smaller one, known as the Grotto of Jeremiah, from the fancy of the Rabbis that the prophet lived in this cavern after the fall of Jerusalem, and wrote the Book of Lamentations with the ruins of the city thus before him. It is a vast excavation, though dwarfed by comparison with its rival close at hand. What appears cannot, however, give any idea of what has been removed, for it is evident that the rock at one time joined that on which the wall stands, and has been cleared away, in the course of ages, till we have the slow ascent that now begins from the Damascus Gate. The quarry extends for about 100 feet into the rock, and underneath it are vast cisterns, the roof of the largest of which is borne up by great square pillars of stone; both the roof and the sides being plastered over. There was excellent water in the cistern, at the depth of nearly forty feet from the top: an illustration of the universal presence of huge reservoirs for collecting surface water, where springs are so rare. In front of the cave is a garden, planted with different kinds of fruit-trees, and separated from the road by a stone wall of no great height. In the garden, the remains of a building of large size, of the time of the Crusaders, were laid bare in 1873; a range of stone mangers showing that it had been the old hostelry of the Templars, which was just outside the Damascus Gate, then known as that of St. Stephen. The spade and pickaxe have still much to unearth, at every step round the city. In the mouth of the cave a Mahommedan family has a cottage, and thus, as the ground over the cavern is a Mahommedan burial-place, this household sleep nightly underneath the dead, from whom they are divided by only a thin strip of rock. This spot, according to Rabbinical tradition, was once "the House of Stoning," that is, the place of public execution under the Jewish law. This is noteworthy, in connection with the question of the site of Calvary.

There is little in the New Testament to fix the exact position of the "mount" on which our Lord was crucified, though the statement that He "suffered without the gate" (Heb 13:12) is enough to prove that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is not on the true site. The name Golgotha, "the Place of a Skull," may well have referred rather to the shape of the ground than to the place so called being that of public execution, and, if this be so, a spot reminding one of a skull by its form must be sought, outside the city. It must, besides, be near one of the great roads, for those who were "passing by" are expressly noticed in the Gospels (Mark 15:29). That Joseph of Arimathæa carried the body to his own new tomb, hewn out in the rock, and standing in the midst of a garden, outside the city (Matt 27:60; John 20:15), requires, further, that Calvary should be found near the great Jewish cemetery of the time of our Lord. This lay on the north side of Jerusalem, stretching from close to the gates, along the different ravines, and up the low slopes which rise on all sides. The sepulchre of Simon the Just, dating from the third century before Christ, is in this part, and so also is the noble tomb of Helena, Queen of Adiabene, hewn out in the first century of our era, and still fitted with a rolling stone, to close its entrance, as was that of our Lord. Ancient tombs abound, moreover, close at hand, showing themselves amidst the low hilly ground wherever we turn on the roadside. Everything thus tends to show that this cemetery was that which was in use in the days of our Lord.

In connection with this, it has been found, by a comparison of many hundred Jewish tombs in Palestine, that the earlier mode of constructing them was to cut a narrow deep hole for each body in the sides of the rock the breadth and length of the human figure, the dead being put into it with the feet towards the outside. At the time of Christ, however, this arrangement had given place to another, in which a receptacle for each body was cut out lengthwise, along the side of the tomb, like a sarcophagus, or grave. The tomb of our Lord must have been of this class, since two angels are described as sitting "the one at the head, and the other at the feet, where the body of Jesus had lain" (John 20:12), which could not have happened if the body had been put into one of the ancient deep holes in the rock. The rolling stone, moreover, such as was used in the case of our Lord's tomb, to close the entrance, was introduced shortly before His day, and is found only in connection with tombs of the later kind. But this kind of tomb, with this mode of closing the entrance, is not found at Jerusalem, except in the tombs outside the Damascus Gate.

On these grounds it has been urged with much force that Calvary must be sought near the city, but outside the ancient gate, on the north approach, close to a main road, and these requirements the knoll or swell over the Grotto of Jeremiah remarkably fulfills.* Rising gently towards the north, its slowly-rounded top might easily have obtained, from its shape, the name of "a Skull"—in Latin, Calvaria; in Aramaic, Golgotha. This spot has been associated from the earliest times with the martyrdom of St. Stephen, to whom a church was dedicated near it before the fifth century, and who could only have been stoned at the usual place of public execution. And this, as Captain Conder shows, is fixed by local tradition at the spot which is still pointed out by the Jews of Jerusalem as "the Place of Stoning," where offenders were not only put to death, but hung up by the hands till sunset, after execution. As if to make the identification still more complete, the busy road which has led to the north in all ages passes close by the knoll, branching off, a little further on, to Gibeon, Damascus, and Ramah. It was the custom of the Romans to crucify transgressors at the sides of the busiest public roads, and thus, as we have seen, they treated our Saviour when they subjected Him to this most shameful of death (Luke 23:35). Here then, apparently, on this bare rounded knoll, rising about thirty feet above the road, with no building on it, but covered in part with Mahommedan graves, the low yellow cliff of the Grotto of Jeremiah looking out from its southern end, the Saviour of the world appears to have passed away, with that great cry which has been held to betoken cardiac rupture—for it would seem that He literally died of a broken heart. Before Him lay outspread the guilty city which had clamoured for His blood; beyond it, the pale slopes of Olivet, from which He was shortly to ascend in triumph to the right hand of the Majesty on High; and in the distance, but clear and seemingly near, the pinkish-yellow mountains of Moab, lighting up, it may be, the fading eyes of the Innocent One with the remembrance that His death would one day bring back lost mankind—not Israel alone—from the east, and the west, and the north, and the south, to the kingdom of God.

The tomb in which our Lord was buried will be, perhaps, for ever unknown, but it was some one of those, we may be sure, still found in the neighbourhood of "the Place of Stoning." Among these, one has been specially noticed by Captain Conder, as possibly the very tomb of Joseph of Arimathæa thus greatly honoured. It is cut in the face of a curious rock platform, measuring seventy paces each way, and situated about 200 yards west of the Grotto of Jeremiah. The platform is roughly scarped on all sides, apparently by human art, and on the west there is a higher piece of rock, the sides of which are also rudely scarped. The rest of the space is fairly level, but there seem to be traces of the foundations of a surrounding wall, in some low mound near the edge of the platform. In this low bank of rock is an ancient tomb, rudely cut, with its entrance to the east. The doorway is much broken, and there is a loophole, or window, four feet wide, on both sides of it. An outer space, seven feet square, has been cut in the rock, and two stones, placed in this, give the idea that they may have been intended to hold in its proper position a rolling stone with which the tomb was closed. On the north is a side entrance, leading into a chamber, with a single stone grave cut along its side, and thence into a cavern about eight paces square and ten feet high, with a well-mouth in its roof.* Pal. Fund Memoirs.

Another chamber, within this, is reached by a descent of two steps, and measures six feet by nine. On each side of it, an entrance, twenty inches broad, and about five and a half feet high, has been opened into another chamber beyond; the passages, which are four and a half feet long, having a ledge or bench of rock at the side. Two bodies could thus be laid in each of the three chambers, which, in turn, lead to two other chambers about five feet square, with narrow entrances. Their floors were still thinly strewn with human bones when Captain Conder explored them.*

"It would be bold," says that careful student of Bible archæology, "to hazard the suggestion that the single Jewish sepulchre thus found, which dates from about the time of Christ, is indeed the tomb in the garden, nigh unto the place called Golgotha, which belonged to the rich Joseph of Arimathæa. Yet its appearance, so near the old place of execution, and so far from the other old cemeteries of the city, is extremely remarkable." I am sorry to say that a group of Jewish houses is growing up round the spot. The rock is being blasted for building-stone, and the tomb, unless special measures are taken for its preservation, may soon be entirely destroyed.* Pal. Fund Rept., 1881, pp. 203-4.

Chapter 24 | Contents | Chapter 26

Philologos | Bible Prophecy Research | The BPR Reference Guide | Jewish Calendar | About Us