by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

Philologos Religious Online Books

Philologos.org

Chapter 21 | Contents | Chapter 23

Cunningham Geikie D.D.

With a Map of Palestine and Original Illustrations by H. A. Harper

Special Edition

(1887)

Close to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are the ruins of the Muristan or Hospice of the Knights of St. John—"muristan" being the Arabic word for a hospital, to which part of the great pile of buildings that once covered the site was devoted. A few paces lead one to a fine old gateway, over which is the Prussian eagle, half of the site having been given to Prussia in 1869. The whole space, once filled up with courts, halls, chambers, a church, and a hospital, is over 500 feet square, and now lies, for the most part, in desolation. The arch by which you enter is semicircular, and was adorned 700 years ago with a series of figures illustrating the months—men pruning, sowing, reaping, threshing, and the like; but the carvings are now very much mutilated. Within, a large space has been cleared of rubbish and abomination by the German Government, the ruins being left to tell their story with silent eloquence. Already, in AD 1048, a church had been built in Jerusalem by Italian merchants, and a hospital attached to it, close to a chapel consecrated to John, at that time Patriarch of Alexandria. From him, the monks, who had undertaken to nurse and care for sick and poor pilgrims, took the name of Johnites, or Brethren of the Hospital. Raised to the dignity of a separate Order in AD 1113, they received great possessions from Godfrey de Bouillon and others. A little later in the twelfth century they were further changed into an Order of clerical monks, some of whom were set apart for military service, others for spiritual service, as chaplains, and the rest as Serving Brothers, to care for the sick, and escort pilgrims to the holy places. Gradually extending itself, the Order gained vast possessions in nearly every part of Christendom, and had a corresponding influence, which secured for it the hearty support of the Papacy, and especial privileges. Their splendid history in Palestine, Cyprus, Rhodes, and Malta, lies outside my limits; but it is pleasant to recall their humbler services to successive generations of poor and sick pilgrims in the once busy halls and chambers of the Muristan. Hundreds of these forlorn wanderers could be received into the great hospital and hospice at once; and who can doubt the devotion on one side, and the gratitude on the other, that must, a thousand times, have made these now ruined walls sacred? He remembers, by whom no good deed done in His name, no tear shed in lowly thanksgiving, is ever overlooked! A hundred and twenty-four stone pillars once supported the arched halls of the palace, but now in the very midst of the city there are only, where the ruins have not been cleared, heaps of rubbish, patches of flowering field-beans, straggling arms of the prickly pear rising forbiddingly aloft, and here and there a fig-tree. Outside the gate there is nothing offensive, as there used to be, but simple stalls, where parti-coloured glass rings from Hebron, and other trifles, are sold. The German Government have made the space given to them within a centre for the German Protestants of Jerusalem, erecting on it a church for them and other buildings.

The bazaars of the city, which are probably much the same as the business part of Jerusalem was in the days of Christ, stretch along the east side of the Muristan, southwards, to David Street. They consist of three arched lanes, lighted only by holes in the roof, and hence very dark, even at noon. The western one is the flesh-market, but displays only parts of sheep and goats, for very few oxen or calves are used for food. In the other lanes, tradesmen of different kinds—fruiterers, oil, grain, and leather sellers—sit, cross-legged, in dark holes in the arched sides, or in front of these, waiting for business. Here you see a row of shoemakers, yonder a range of pipe-stem borers. More than one of the tradesmen, in the intervals of business, sits at the mouth of his den with the Koran open before him, his left hand holding paper on which to write his comments, his right holding the pen, dipped from time to time in the brass "inkhorn" stuck in his girdle (Eze 9:2,3,11). At a recess in the side, on which light falls, sits a bearded old man, duly turbaned, with flowing robes, a broad sash round his waist inside his light "abba," his slippers on the ground before him, his feet bent up beneath him, his long pipe resting against the bench at his side, it being impossible that he should use it for the moment, as he is busy writing a letter for a woman who stands veiled, behind, giving him instructions what to say. He is a professional letter-writer, a class of which one may see representatives in any Oriental city, just as they could be seen in olden times in English towns, before education was so widely spread as it is now. The paper is held in the left hand, not laid on a desk, and the scribe writes from the right hand to the left, with a piece of reed, pointed like a pen, but without a split—the same instrument, apparently, as was used in Christ's day, for in the New Testament a pen is called kalamos, a reed, and its name is still, in Arabic, kalem, which has the same meaning. The pens and ink are held in a brass case, which is thrust into the girdle when not in use, the hollow shaft containing the pens, and a small brass box which rises on one side at the end, the ink, poured into cotton wadding or on palm threads, to keep it from spilling. A few hints given him are enough; off he goes, with all manner of Oriental salaams and compliments, setting forth, in the fashionable, high-flown style natural to the East, what the poor girl wishes to say.

There are two words in the Old Testament for a pen; one of these occurs only twice, and is translated differently each time. Aaron is said to have "fashioned" the golden calf with "a graving tool" (Exo 32:4), but the same word is used by Isaiah for a pen—"Take thee a great tablet and write upon it with the pen of a man" (Isa 8:1). This shows that heret, at least, meant a metal stylus, or sharp-pointed instrument, with which surfaces like that of wax, spread on tablets, or even the surface of metal plates, might be marked with written characters. The other word, et, occurs four times, and in two of these the implement is said to be of iron (Job 19:24; Jer 17:1), so that, so far as the Old Testament indicates, reed pens had not come into use till its books had all been written. The word translated "inkhorn" is found only in Ezekiel (Eze 9:2,3,11), and owes its English rendering to our ancestors having horns for ink, the Hebrew word meaning simply a round vessel or cup, large or small, and, as we see in the case of the prophet, worn, at least sometimes, in the girdle. It may, therefore, have been similar to the "inkhorns" at present universal in the East.

Writing was known in Palestine long before the invasion of the Hebrews, as we see in the name of Kirjath Sepher—"Book Town" (Josh 15:15)—but was brought by them from Egypt, for, while there, they had shoterim among them, the class known in our Bible as "scribes" or "writers" (Exo 5:6).* It is not surprising, therefore, to read of Moses "writing in the book" (Exo 17:14, 24:4), or that the priests could write (Num 5:23), or that the people generally could do so, more or less. They were to write parts of the law on their door-posts and gates (Deut 6:9, 11:20); a husband, in divorcing his wife, was to "write her a bill, or book, of divorcement" (Deut 24:1,3), and the king was to write out the Book of the Law (Deut 17:18). Letters were written by Jezebel, in the name of Ahab, and sealed with his seal; by Jehu, Hezekiah, Rabshakeh, and many others.

The seal is a very important matter, as the name of the wearer is engraved on it, to be affixed by him to all letters and documents. It is, therefore, constantly carried on the person, and when trusted to another, virtually empowers him to act in its owner's place. Even Judah had his signet (Gen 38:18), which he perhaps wore as the bridegroom in Canticles wore his, on the breast, suspended by a string (Song 8:6). The seal is used in the East in ways peculiar to those regions—to seal up doors, gates, fountains, and tombs. The entrance to the den of lions was sealed upon Daniel with the signet of the king and of his lords; the bride in Canticles, as we already know, is compared for her purity to a fountain sealed; and we all remember how the guard made the sepulchre of our Lord "sure, sealing the stone" (Song 4:12; Dan 6:17; Matt 27:66). A letter must be sealed, if an insult be not actually intended, so that when Sanballat sent his servant to Nehemiah with an open letter in his hand, he offered the great man a deliberate affront (Neh 6:5). The ink now used is made of gum, lampblack, and water, and is said never to fade. Small horns are still used in some parts of Egypt to hold it. In sealing a letter or document, a little ink is rubbed over the face of the seal, a spot damped on the paper, and the seal pressed down; but when doors or the like are spoken of as sealed, it was done by impressing the seal on pieces of clay (Job 38:14) or other substances. When Pharaoh "took off his ring from his hand and put it on Joseph's hand" (Gen 41:42), it was the sign of his appointment to the Viziership of Egypt, just as a similar act in Turkey, now, installs a dignitary as Grand Vizier of the empire.* Translated wrongly "officers." The RV, as in so many other cases, retains this mistranslation.

The display in the stalls of Jerusalem varies of course with the season. In the market before the citadel, cauliflowers, and vegetables generally, are the main features in March, but as the year advances, cucumbers, tomatoes, grapes, figs, prickly pears, pomegranates, from the neighbourhood, and oranges, lemons, and melons from Joppa and the plain of Sharon, are abundant. Roses are so plentiful in the early summer that they are sold by weight for conserves and attar of roses, and every window and table has its bunch of them. In the streets and bazaars, during the busy part of the day, all is confusion on the horrible causeway, and image-like stolidity on the part of many of the sellers. The butchers, however, like members of the trade elsewhere, shout out their invitations to come and buy, and the fruit-sellers in their quarter rival or even outdo them by very doubtful assurances that they are parting with their stock for nothing! Women from Bethany or Siloam, in long blue cotton gowns, or rather sacks, loosely fitting the body, without any attempt at a waist, sit here and there on the side of the street, at any vacant spot, selling eggs, olives, cucumbers, tomatoes, onions, and other rural produce. Bright-coloured kerchiefs tied round the head distinguish them from their sisters of Bethlehem, who have white veils over their shoulders and bright parti-coloured dresses, and are seen here and there trying their best to turn the growth of the garden or orchard into coin. Young lads wander about offering for sale flat round "scones" and sour milk. The grocer sits in his primitive stall, behind baskets of raisins, dates, sugar, and other wares, pipe in mouth. No such tumble-down establishment could be found in the worst lane of the slums of London. The two half-doors—hanging awry—which close it at night, would disgrace a barn; the lock is a wooden affair, of huge size; a rough beam set in the wall perhaps seven feet from the ground, supports the house overhead, while some short poles resting on it bear up a narrow coping of slabs, old and broken, to keep off, in some measure, the sun and rain. The doors, when closed, do not fit against this beam by a good many inches; and there is the same roughness inside. Rafters, coarse, unpainted, twisted, run across; a few shelves cling, as they best can, to the walls; hooks here and there, or nails, bear up part of the stock, but the whole is a picture of utter untidiness and poverty which would ruin the humblest shop in any English village. A cobbler's shop, yonder, next to an old arch, is simply the remains of a house long since fallen down, except its ground arch, which is too low for a tall man to stand in it. The prickly pear is shooting out its great deformed hands overhead; grass and weeds cover the tumbling wall. Beams, never planed but only rough-hewn, no one could tell how long ago, form the door-post, sill, and lintel, against which a wooden gate, that looks as if it were never intended to be moved, is dragged after dark. A low butcher's block serves as anvil on which to beat the sole-leather; over the cave-mouth a narrow shelf holds a row of bright red and yellow slippers with turned-up toes, and there are two other and shorter shelves with a similar display. The master is at work on one side, and his starved servant on the other, close to the entrance, for there is no light except from the street. The slippers of the two lie outside, close to them, and a jar of water rests near, from which they can drink when they wish. A few old short boards jut out a foot or two over the shelf of slippers above, to give a trifle of shade. There is no paint; no one in the East thinks of such a thing; indeed, such dog-holes as most shops are defy the house-painter. Arabs and peasants, on low rush stools, sit in the open air, before a Mahommedan cafe, engrossed in a game like chess or draughts, played on a low chequered table; the stock of the establishment consisting of the table, a small fire to light the pipes and prepare coffee, some coffee-cups, water-pipes, and a venerable collection of red clay pipe-heads with long wooden stems. Grave men sit silently hour after hour before such a house of entertainment, amusing themselves with an occasional whiff of the pipe, or a sip of coffee. But all the shops are not so poor as the cobbler's, though wretched enough to Western eyes. David Street, with its dreadful causeway, can boast of the goods of Constantinople, Damascus, Manchester, and Aleppo, but only in small quantities and at fabulous prices. Towards the Jewish quarter most of the tradesmen are shoemakers, tinsmiths, and tailors, all of them working in dark arches or cupboards, very strange to see. Only in Christian Street, and towards the top of David Street, can some watery reflections of Western ideas as to shopkeeping be seen.

To walk through the sloping, roughly-paved, narrow streets of the modern Jerusalem, seemed, in the unchanging East, to bring back again those of the old Bible city. One could notice the characteristics of rich and poor, old and young, townspeople and country folks, of both sexes, as they streamed in many-coloured confusion through the bazaars and the lane-like streets. The well-to-do townspeople delight to wear as great a variety of clothes as they can afford, and as costly as their purse allows. Besides their under-linen and several light jackets and vests, they have two robes reaching the ankles, one of cloth, the other of cotton or silk. A costly girdle holds the inner long robe together, and in it merchants always stick the brass or silver pen and ink case (Eze 9:2). A great signet ring is indispensable. Many also carry a bunch of flowers, with which to occupy their idle fingers when they sit down or loiter about. The head is covered with a red or white cap, round which a long cotton cloth is wound, forming the whole into a turban.

The peasant is clad much more simply. Over his shirt he draws only an "abba" of camels'- or goats'-hair cloth, with sleeves or without, striped white and brown, or white and black. It was, one may think, just such a coat which Christ referred to when He told the Apostles not to carry a second (Matt 10:10). Many peasants have not even an abba, but content themselves with the blue shirt, reaching their calves, and this they gird round them with a leather strap, or a sash, as the fishermen did in the time of St. Peter (John 21:7). If he has any money, the peasant carries it in the lining of his girdle; and hence the command to the Apostles, who were to go forth penniless, that they were to take no money in their girdles (Mark 6:8 [Greek]). Elijah and John the Baptist wore leathern girdles; Jeremiah had one of linen (2 Kings 1:8; Matt 3:4; Jer 13:1). It is thus still with the country people, but the townsfolk indulge themselves in costly sashes. The water-carriers, who bend under their huge goat-skin bags of the welcome liquid, selling it to any customers in the streets whom they may attract by their cry or by the ringing of a small bell, or taking it to houses, are the most meanly clad of any citizens. A shirt, reaching to the knees, is their only garment. Their calling, and that of the hewers of wood, is still the humblest in the community, just as it was in the days when Moses addressed Israel before his death, for he puts the heads of the tribes at the top, and the hewers of wood and drawers of water at the bottom, of his enumeration of classes; setting even the foreigner who might be in their midst above these latter (Deut 29:10,11). The Gibeonites, whom Joshua was compelled by his oath to spare, were thus doomed to the hardest fate, next to death, that could be assigned them, when sentenced to perpetual slavery, with the special task of hewing wood and drawing water for the community (Josh 9:23,27). It is in allusion to water being borne about in skins like those of to-day that the Psalmist in his affliction prays God to "put his tears into His bottle" (Psa 56:8), that they might not go unmarked. Female dress is strangely like that of the men, but while the poor peasant-woman or girl has often only a long blue shirt, without a girdle, her sisters of the town, where they are able to do so, draw a great veil over various longer and shorter garments, and this covers them before and behind, from head to foot, so that they are entirely concealed. It is this which puffs out, balloonlike, as I have already noticed, when they pass by; but it is not probable that Hebrew women wore such a thing, as they seem to have appeared in public, both before and after marriage, with their faces exposed. Hence, the Egyptians could see the beauty of Sarah, and Eliezer noticed that of Rebekah, while Eli saw the lips of Hannah moving in silent prayer (Gen 12:14, 24:16, 29:10; 1 Sam 1:12). The veil, in fact, seems to have been worn only as an occasional ornament, as when the loved one, in Canticles, is said to have behind her veil eyes like dove's eyes, and temples delicate in tint as the pomegranate (Song 4:1,3, 6:7 [Heb.]); or by betrothed maidens before their future husbands, as when Rebekah took a veil and covered herself before Isaac met her (Gen 24:65); or when concealment of the features was specially desired for questionable ends (Gen 38:14).

A natural and earnest wish of a poor girl of Jerusalem is to be able to hang a line of coins along her brow and down her cheeks, as is common elsewhere, for she sees rich women round her with a great display of such adornment on their hair, and notices that even the children of the wealthy have numbers of small gold coins tied to the numerous plaits which hang down their shoulders; indeed, some children have them tied round their ankles also. The double veil, falling both before and behind, is not so frequent as in Egypt, but it would appear to have been more common among Jewish women anciently, at least in worship, if we may judge from the command of St. Paul that the women should never appear in the congregation at Corinth without having their heads covered (1 Cor 11:5). Among the poorer classes in Jerusalem, as elsewhere in Palestine, both men and women tattoo themselves. The women darken their eyelids, to brighten the eyes and make them seem larger, and often puncture their arms fancifully, as a substitute for arm-rings. Among the peasant-woman the chin and cheeks, also, are often seen with blue punctured marks, and the nails are very generally dyed red.

From the bazaars, the street running almost directly north brought me to the Damascus Gate, the entrance to the city from Samaria and all the northern country. The slope of the ground here shows very clearly the line dividing the eastern from the wester hill—Moriah from Zion—a depression, once known as the Cheese-makers' Valley, still running towards the ancient Temple enclosure. Originally this was a deep gully, opening into the Valley of Jehoshaphat at its junction with that of the Sons of Hinnom, on the south-east corner of the city; but it is now well-nigh filled up with the rubbish of many centuries, so that it can only be detected near the Damascus Gate. No more thoroughly Oriental scene can be imagined than that offered when, standing at this gate, you look at the two streets which branch off from it, south-west and south-east. The houses are very old, with a thick growth of wall-vegetation wherever it can get a footing. Flat roofs one cannot see, but only the low domes covering the tops of arches. The house-corners, the few pieces of sloping roof, the ledges jutting out here and there, the awnings of mats stretched on epileptic poles, and projecting over the street, the woodwork filling in the round of arches used as cafes of for business, and even the time-worm stones of the buildings, as a whole, form a picture of dilapidation which must be seen to be realised.

A nondescript building of one storey faces you on the left hand, the dome of the arch which constitutes the structure rising through the flat roof. Another house of two storeys joins it on the right, the upper storey rising like a piece of a tower, slanting inwards on all sides, with a parapet on the top, through which a row of triangles of clay pipes supply ornament and peep-holes. One very small window in the tower is the only opening for light, except two low arches, the semicircles of which are filled up with rough old woodwork. The causeway is, of course, antediluvian. Figures, in all kinds of strange dress, sit on low rush stools in the street along the front of this building, some of them enjoying the delicacies of a street cook, whose brazier is alight to provide whatever in his art any customer may demand. Some sit cross-legged on the stones; others literally on nothing, their feet supporting them without their body touching the ground: a feat which no Occidental could possibly perform for more than a few minutes together. Camels stalk leisurely towards the Gate; a man on the hump of the foremost, with his feet out towards its neck. Long-muzzled yellow street-dogs lie about, or prowl after scraps. On the right a two-leaved door, which would disfigure a respectable barn, hangs open, askew, and reveals the treasures of some shopkeeper; grave personages sit along the wall beside deep baskets of fruit; a turbaned figure passes with his worldly all, in the shape of some sweetmeats, on a tray, seeking to decrease his stock by profitable sale. A wretched arch admits to the street beyond, but into this, with its stream of passengers, I did not enter. At the head of the street on the left hand, leading to the south-east, a group of Bedouins were enjoying their pipes in the open air, and of course there were idlers about; but the rest of the street was almost deserted. It leads to the Austrian Hospice, a well-built modern Home for Pilgrims, where, for a gratuity of five francs a day, one may forget, in the midst of Western comfort, that he is in the East. From this point you enter a street famous in later monkish tradition as the Via Dolorosa—the way by which our Saviour went from the judgment-seat of Pilate to His crucifixion. That no reliance can be placed on this identification is, however, clear from the self-evident fact that the route taken must depend on the situation of Pilate's Hall, of which nothing is known, though it seems natural that it should have been on the high ground of Zion, the site of the palace of Herod, rather than in the confined and sordid lanes of the city. We may, moreover, feel confident that the Jerusalem of Christ's day perished, for the most part, in the siege of Titus, so that even the lines of the ancient streets, traced over the deep beds of rubbish left by the Romans, must be very different, in many cases, from those of the earlier city.

This, however, has in no degree fettered monkish invention, for there are fourteen stations for prayer in the Via Dolorosa, at which different incidents in the story of the Gospels are said to have taken place. The street rises gently to an arch apparently of the time of Hadrian, and originally an arch of triumph, now said to mark the spot where Pilate, pointing to the bruised and stricken Saviour, said, "Behold the Man!" (John 19:5). There were once, it would seem, two side arches, with a larger one in the middle, but only the central one, and that on one side, are now standing; the other, and even part of the centre span, being built into the church of the Sisters of Zion. Before reaching this you pass the place at which Simon of Cyrene is said to have taken up the cross, and that where Christ fell under its weight. The house where Lazarus of Bethany dwelt after being raised from the dead, and the mansion of Dives, are also shown.

Click pics for larger views

Pilate's judgment-hall is affirmed to be identical with the mansion of the Pasha of Jerusalem, at the Turkish barracks on the north-west corner of the Temple enclosure. This building is said to be the old tower called Antonia by the Romans, and used by them to control the worshippers at the Passover season; but the main structure is comparatively modern, though some old stones remain at the gateway. On these rises, to a height of about forty feet, a square tower of slight dimensions, from which an archway twelve or fourteen feet high bends over the street. A mass of old wall surmounts this and fills in what was once a second lofty arch, surmounted by a great window, only the bottom of which now remains. A huge growth of prickly pear leans over the broken street-wall below, the side of the tower is partly fallen, and wild vegetation flourishes wherever it has been able to get a foothold. Passing on a short distance, we come to a pool on the right, which claims to be that of Bethesda, where Christ healed the blind man, although, as Capt. Conder points out,* it is not clearly mentioned before the tenth century, and may have been built by the Romans or early Arabs. This huge basin, in great part excavated in the living rock, is 360 feet long, 126 feet wide, and 80 feet deep; but it is so filled with a mass of rubbish, rising thirty-five feet above a great part of the bottom, that it is difficult to realise the full size or depth. I got access to the surface through a hole in a wall, but had to take the greatest care to avoid the pollutions which covered nearly every step of my way through weeds and bushes to the edge. Such a work speaks for the grand ideas of its originator, whoever he may have been. The north wall of the Temple enclosure rises high over the pool to the south, and deepens the impression of its hugeness. Steps, very irregular, lead down to the bottom at the west end, and the pressure of the water is provided against at the east end, where the hill rapidly descends, by a dam forty-five feet thick, which serves also as part of the city wall (John 5:2). A smaller pool, once called "Struthion," north-west of Bethesda, but now built over, is thought by others to have been Bethesda. But the true pool of Bethesda has been shown by Sir Charles Warren** to have been discovered

during excavations beside the church of St. Anne, a little north of the great pool at the north-east corner of the wall of Jerusalem. It has been found, in accordance with ancient tradition, to consist of two pools side by side. One of these is thirty feet deep, fifty-five feet long from east to west, and twelve and a half feet broad from north to south, a flight of steps leading down its side from the east. The second pool, alongside of this one, is sixty feet long, and of the same breadth as the other: Sir Charles Warren thinking that two pools, once near the church of St. Anne, close by, were "the Twin Pools" which were believed in the early Christian centuries to be Bethesda, while Captain Conder says that the present pool is not clearly mentioned before the tenth century.

About seventy-five yards north of the great pool is a fine specimen of Crusading architecture—the triple-naved pure Gothic church of St. Anne, formerly used as a mosque, but after many centuries given back to the Christians as a gift of the Sultan to Napoleon III at the close of the Crimean War. A huge cistern excavated in the rock below it and carefully cemented is actually claimed to have been the home of St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary.* Tent Work in Palestine, p. 185.

** Recovery of Jerusalem, p. 198.

West of the same pool three gates open into the Temple enclosure, now Harem esh Sheriff, but entrance by these is strictly prohibited to any save Mahommedans. Indeed, it is only a few years since that unbelievers were permitted to enter at all, and many a rash intruder, ignorant of the danger, has in former days been killed for daring to intrude on such holy ground. The bitter fanaticism of the past has, however, yielded so far that a fee, paid through one of the consulates, enables strangers to enter, if duly attended by one of the richly-bedizened "cavasses," or servants of such an office. I was thus enabled, in company with a party of Americans, to go over the mysterious space, which, indeed, has sights one cannot well forget. The great Silseleh Gate, at the foot of David Street, and thus almost in the centre of the western side of the enclosure, admits you by two or three steps upwards to the sacred precincts, which offer in their wide open space of thirty-five acres, the circumference nearly equal to a mile,* a delightful relief, after toiling through the narrow and filthy streets. Lying about 2,420 feet above the Mediterranean, this spot is comparatively cool, even in summer. The surface was once a rough hill sloping or swelling irregularly, but a vast level platform has been formed, originally under Solomon, by cutting away the rock in some places, raising huge arched vaults at others, and elsewhere by filling up the hollows with rubbish and stones.

Near the north-west corner the natural rock appears on the surface, or is only slightly covered, but it was originally much higher. The whole hill, however, has been cut away at this part, except a mass at the angle of the wall, rising with a perpendicular face, north and south, forty feet above the platform. On this, it seems certain, the Roman Fort Antonia was built, for Josephus speaks of it as standing at this corner on a rock fifty cubits high.* This platform is, moreover, separated from the north-eastern hill by a deep trench, fifty yards broad, and this, also, agrees with what the Jewish historian says of Antonia. The north-east corner has been "made" by filling up a steep slope with earth and stones, but the chief triumph of architecture was seen on the south, where the wall rose from the valley to a height almost equal to that of the tallest of our church-spires, while above this, in the days of Herod's Temple, rose the royal porch, a triple cloister, higher and longer than York Cathedral; the whole, when fresh, glittering with a marble-like whiteness. The vast space thus obtained within was utilised in many ways.* On the map in The Recovery of Jerusalem, the entire space is about 4,800 feet round, about 500 feet less than a mile.

Level as is the surface thus secured by almost incredible labour, it covers wonders unsuspected, for the ground is perfectly honeycombed with cisterns hewn in the rock; the largest being south of the central height. All appear to have been connected together by rock-cut channels, though their size was so great in some cases that, as a whole, they could probably store more than 10,000,000 gallons of water; one cistern—known as the Great Sea—holding no less than 2,000,000 gallons. The supply for this vast system of reservoirs seems to have been obtained from springs, wells, rain, and aqueducts, at a distance. It is, indeed, a question whether any natural springs existed in or near Jerusalem, except the Fountain of the Virgin in the Kedron valley.* Jos. Bell. Jud., v. 5, 8.

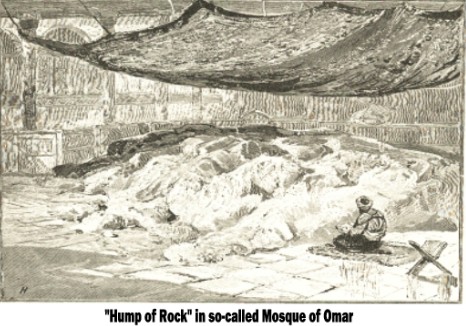

Nearly in the centre of the great open area is a raised platform of marble, about sixteen feet high, reached by broad steps, and on this stands the so-called Mosque of Omar, built over the naked top of Mount Moriah, whence Mahomet is fabled to have ascended to heaven. Dated inscriptions from the Koran represent that it was built between the years AD 688 and AD 693, under the reign of the Caliph Abd-el-Melek. It has eight sides, each sixty-six feet in length, so that it is over 500 feet in circumference. Inside, it is 152 feet across. A screen, divided by piers and columns of great beauty, follows the lines of the eight sides, at a distance of thirteen feet from them, and, then, within this, at a further distance of thirty feet, is a second screen, round the sacred top of the mountain, relieved in the same way with pillars, which support aloft the beautiful dome, sixty-six feet wide at its base. Outside, the height of the wall is thirty-six feet, and it is pierced below by four doors. For sixteen feet from the platform it is cased in different-coloured marbles, but at that height there is an exquisite series of round arches, seven on each face, two-thirds of them pierced for windows; the rest with only blind panels. The upper part was at one time inlaid with mosaics of coloured and gilt glass, but these are now gone. The whole wall, above the marble casing, is covered with enamelled tiles, showing elaborate designs in various colours, a row in blue and white on which are verses of the Koran in interlaced characters running round the top. Within, the piers of the screens are cased in marble, and their capitals gilded; the screens themselves, which are of fine wrought iron, being very elaborate, while the arches under the dome are ornamented with rich mosaic, bordered above by verses from the Koran, and an inscription stating when the mosque was built, the whole in letters of gold. The walls and dome glitter with the richest colours, in part those of mosaics, and the stained glass in the windows exceeds, for beauty, any I have seen elsewhere. There could, indeed, I should suppose, be no building more perfectly lovely than the Mosque of Omar, more correctly known as the Dome of the Rock.

All this exquisite taste and lavish munificence is strangely expended in honour of a hump of rock, the ancient top of Morah, which rises in the centre of the building, within the second screen, nearly five feet at its highest point, and a foot at its lowest, above the marble pavement, and measures fifty-six feet from north to south, and forty-two feet from east to west. Had the mosque been raised in honour of the wondrous incidents connected with the spot in sacred history, it would have had a worthy aim; but to the Mahommedan it is sacred, almost entirely, because he believes that this vast rock bore the Prophet up, like a chariot, to Paradise; the finger-marks of the angel who steadied it in its amazing flight being still shown to the credulous. Yet, foolish legend discarded, this rough mountain-top has an absorbing interest to the Jew and the Christian alike. It was here that the Jebusite, Araunah, once had his threshing-floor (2 Sam 24:18,22; 1 Chron 21:18). It is, as I have said, the highest point of Mount Moriah, which sinks steeply to the valley of the Kedron, on the east, and more gently in other directions. On that yellow stretch of rock the heathen subject of King David heaped up his sheaves and cleansed with his shovel or fork the grain which his threshing-sledge had separated from the straw; throwing it up against the wind, before which the chaff flew afar, as is so often brought before us in the imagery of the sacred writers (Psa 1:4, 35:5; Job 21:18). The royal palace on Zion must have looked down on this threshing-floor, and it may thus have already occurred to David's mind as a site for his Temple, before the awful incident which finally decided his choice (2 Chron 3:1). Nor could any place so suitable have been found near Jerusalem; and it appears, besides, to have had the special sacredness of having been the scene, in far earlier times, of the offering of Isaac by the Father of the Faithful, though Araunah's use of it shows that it had not on that account been set apart from common ground. In later days, also, a special sanctity is associated with this spot as that on which, in all probability, the great altar of the Jewish Temple stood. Sir Charles Warren found huge vaults existing on the north side of the Temple area, and if these, and the loose earth over them,

were removed, that end of the rock would show a perpendicular face, part of it having in ancient times been cut away, while in another direction a gutter cut in the rock has been found, perhaps made to drain off the blood from the sacrifices on the altar.*

All this exquisite taste and lavish munificence is strangely expended in honour of a hump of rock, the ancient top of Morah, which rises in the centre of the building, within the second screen, nearly five feet at its highest point, and a foot at its lowest, above the marble pavement, and measures fifty-six feet from north to south, and forty-two feet from east to west. Had the mosque been raised in honour of the wondrous incidents connected with the spot in sacred history, it would have had a worthy aim; but to the Mahommedan it is sacred, almost entirely, because he believes that this vast rock bore the Prophet up, like a chariot, to Paradise; the finger-marks of the angel who steadied it in its amazing flight being still shown to the credulous. Yet, foolish legend discarded, this rough mountain-top has an absorbing interest to the Jew and the Christian alike. It was here that the Jebusite, Araunah, once had his threshing-floor (2 Sam 24:18,22; 1 Chron 21:18). It is, as I have said, the highest point of Mount Moriah, which sinks steeply to the valley of the Kedron, on the east, and more gently in other directions. On that yellow stretch of rock the heathen subject of King David heaped up his sheaves and cleansed with his shovel or fork the grain which his threshing-sledge had separated from the straw; throwing it up against the wind, before which the chaff flew afar, as is so often brought before us in the imagery of the sacred writers (Psa 1:4, 35:5; Job 21:18). The royal palace on Zion must have looked down on this threshing-floor, and it may thus have already occurred to David's mind as a site for his Temple, before the awful incident which finally decided his choice (2 Chron 3:1). Nor could any place so suitable have been found near Jerusalem; and it appears, besides, to have had the special sacredness of having been the scene, in far earlier times, of the offering of Isaac by the Father of the Faithful, though Araunah's use of it shows that it had not on that account been set apart from common ground. In later days, also, a special sanctity is associated with this spot as that on which, in all probability, the great altar of the Jewish Temple stood. Sir Charles Warren found huge vaults existing on the north side of the Temple area, and if these, and the loose earth over them,

were removed, that end of the rock would show a perpendicular face, part of it having in ancient times been cut away, while in another direction a gutter cut in the rock has been found, perhaps made to drain off the blood from the sacrifices on the altar.*

Underneath the rock, reached by a flight of steps, is a large cave, the roof of which is about six feet high, with a circular opening in it, through which light enters. The floor sounds hollow, and so do the rough sides: a proof, say the Mahommedans, that this mountain is hung in the air. There is, however, probably, a lower cave, or possibly a well, but no one is allowed to find this out. Fantastic legends, connected with every part of the whole summit, are repeated to the visitor; but to the Christian the place is too sacred to pay much heed to them. To the Mahommedan world it is "the Rock of Paradise, the Source of the Rivers of Paradise, the Place of Prayer of all Prophets, and the Foundation Stone of the World."* Recovery of Jerusalem, pp. 219-222.

Though these religionists claim with perfect justice that the mosque was built by Caliph Abd-el-Melek, it is by no means certain that there were not various predecessors of this beautiful building. Mr. James Fergusson believed that it, rather than the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, was in all essential particulars, the very Church of the Resurrection, built by Constantine over the place where our Lord was believed to have been buried, which, in his opinion, was the cave under this rock. Other experts have thought that a church stood here between the reigns of Constantine and Justinian—some say, in the first third of the sixth century. It was, at any rate, for generations a Christian church under the Crusaders, and Frankish kings offered up their crowns to Christ before the rock on the day of their coronation.

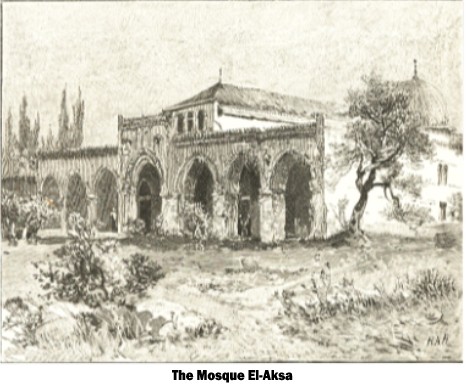

The Mosque el-Aksa, which stands at the south end of the great enclosure, was originally a basilica or church built by Justinian in the sixth century in honour of the Virgin. The noble facade of arches, surmounted by a long range of pinnacles, is, however, Gothic, and appears to have been the work of

the Crusaders. Within there are seven aisles, of various dates, pillars a yard thick, dividing the nave from the side aisles, and a dome rising over the centre of the transept; but the effect of the whole is poor, for the building, though 190 feet wide, and 270 feet broad, is whitewashed and coarsely painted. By this church the Templars once had their residence; and the twisted columns of their dining-hall still remain. The struggle between Moslems and Christians, at the capture of Jerusalem, was especially fierce in this building, the greater part of the ten thousand who perished by the sword of the Christian warriors falling inside and round these walls. A flight of steps outside the principal entrance leads down to a wonderful series of arched vaults, which, with the great sculptured pillars, help one to realise vividly the vast substructures needed to bring this part of the hill to the general level. When they were built, however, is a question as yet undecided; only a small portion here and there is very old.

The Mosque el-Aksa, which stands at the south end of the great enclosure, was originally a basilica or church built by Justinian in the sixth century in honour of the Virgin. The noble facade of arches, surmounted by a long range of pinnacles, is, however, Gothic, and appears to have been the work of

the Crusaders. Within there are seven aisles, of various dates, pillars a yard thick, dividing the nave from the side aisles, and a dome rising over the centre of the transept; but the effect of the whole is poor, for the building, though 190 feet wide, and 270 feet broad, is whitewashed and coarsely painted. By this church the Templars once had their residence; and the twisted columns of their dining-hall still remain. The struggle between Moslems and Christians, at the capture of Jerusalem, was especially fierce in this building, the greater part of the ten thousand who perished by the sword of the Christian warriors falling inside and round these walls. A flight of steps outside the principal entrance leads down to a wonderful series of arched vaults, which, with the great sculptured pillars, help one to realise vividly the vast substructures needed to bring this part of the hill to the general level. When they were built, however, is a question as yet undecided; only a small portion here and there is very old.

You could wander day after day through one part or another of the strange sights of the Temple enclosure, and never tire. In one place is a Mahommedan pulpit, with its straight stair, and a beautiful canopy resting on light pillars: a work of special beauty. Minarets rise at different points around, enhancing the picturesque effect. Fountains, venerable oratories, and tombs dot the surface. The massive Golden Gate still stands towards the centre of the eastern wall, though long since built up, from a tradition that the Christians would one day re-enter it in triumph. Seen from the inside it is a massy structure, with a flat low-domed roof, carved pilasters, and numerous small arches, slowly sinking into decay. It was always the chief entrance to the Temple from the east, but, apart from later tradition, would seem to have been kept closed from a very early period (Eze 44:1,2). In its present form, the gateway dates from the third or, perhaps, the sixth century after Christ, and till AD 810 there was a flight of steps from it down to the Kedron valley. During the time of the Crusaders the gate was opened on Palm Sunday, to allow the Patriarch to ride in upon an ass, amidst a great procession bearing palm-branches, and strewing the ground before him with their clothes, in imitation of the entry of Christ. But it will, I fear, be long before a representative of the true Messiah rides through it again.

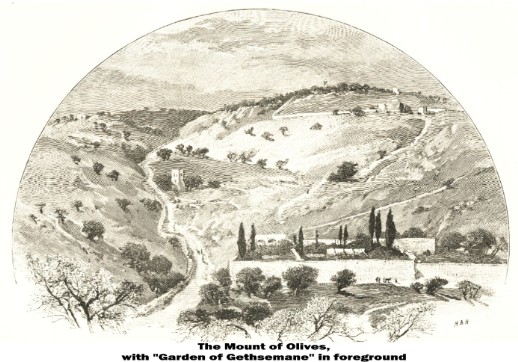

The view of the Mount of Olives from the Temple area is very fine, for only the Kedron valley, which is quite narrow, lies between the Mount and Moriah. Mount Zion rises on the south-west, but it is only by the houses and citadel that you notice the greater elevation. The Crescent flag is seen waving over the old Tower of David. On the south-east the eye follows the windings of the Valley of Jehoshaphat, which is the name given to the upper part of that of the Kedron. Into it were, one day, to fall the streams which Ezekiel describes in his vision of the restored sanctuary, as destined to pour forth from under the door-sill of the Temple, and gather to such a body as will reach the Dead Sea, deep down in its bed to the east, changing its life-destroying water to healing floods (Eze 47:1-8). From south-west to north-west the city rises like an amphitheatre round the sacred area, as Josephus noticed in his day.* Part of this wide space is paved with slabs of limestone, feathered with grass at every chink, much of this being green, and sprinkled, in spring-time, with thousands of bright flowers. Olive-trees and cypresses flourish here and there, and give most welcome shade.

It was much the same thousands of years ago on this very spot. The Psalmist could then cry out, "I am like a green olive-tree in the house of God." "Those that be planted in the house of the Lord shall flourish in the courts of our God. They shall bring forth fruit in old age; they shall be fat and flourishing" (Psa 52:8, 92:13,14). Here, protected by high walls, reclining under the peaceful shade of some tree, the pious Israelite realised his deepest joy, as he meditated on God, or bowed in prayer towards the Holy of Holies, within which Jehovah dwelt over the Mercy-seat (Exo 25:22; Psa 99:1). Now in soft murmurs, now in loud exclamations of rapture, now in tones of sadness, now in triumphant singing, his heart uttered all its moods. It was his highest conception of perfect felicity that he "should dwell in the house of the Lord for ever" (Psa 23:6). Hither, from Dan to Beersheba, streamed the multitude that kept holyday, ascending with the music of pipes and with loud rejoicings to the holy hill, bringing rich offerings of cattle, sheep, goats, and produce and fruit of all kinds, to the King of kings (2 Chron 25:7, 30:5,24; Deut 12:5). Here the choirs of Levites sang the sacred chants; here the high priest blessed the people, year by year, as he came forth from the Holy of Holies, into which he had entered with the atoning blood, his reappearance showing that his mediation had been accepted, and their sins forgiven. And so Christ, now within the holy place in the heavens pleading the merits of His own blood, will one day come forth again, and "appear to them that look for Him, without a sin-offering, unto salvation" (Heb 9:28). Here, as we are told by the Son of Sirach (Ecclus 50:16,17,20), thousands on thousands cast themselves on the ground, at the sight of their priestly mediator, fresh from the presence of the holy and exalted Lord of Hosts. "Then shouted the sons of Aaron, and sounded the silver trumpets, and made a great noise to be heard, for a remembrance before the Most High. Then all the people hasted, and fell down to the earth upon their faces, to worship the Lord God Almighty, the Most High. Then he went down, and lifted up his hands over the whole congregation of the children of Israel, to give the blessing of the Lord with his lips, and to rejoice in His name." And at an earlier time it was here, upon the entrance of the ark into the newly-built Holy of Holies, at the Temple dedication under Solomon, that "it came even to pass, as the trumpeters and singers, as one, made one sound to be heard in praising and thanking the Lord; and when they lifted up their voice with the trumpets and cymbals and instruments of music, and praised the Lord, saying, For He is good; for His mercy endureth for ever: that then the house was filled with a cloud, for the glory of the Lord had filled the house of God" (2 Chron 5:13,14). The heavenly and earthly Fatherland of the Israelite thus seemed here to fade into each other. Who does not remember the touching cry of the Jewish prisoner from the sources of the Jordan, on his way to exile? "As the hart panteth after the water-brooks, so panteth my soul after Thee, O God...For I had gone with the multitude, I went with them to the house of God, with the voice of joy and praise, with a multitude that kept holyday" (Psa 42:1,4). But peaceful as this place is now, and sacred as it was in its earlier days, how often has it been the scene of the most embittered strife, since the times of Solomon! The first Temple, with all its glory, had gone up in smoke and flames, amidst the shouts of Nebuchadnezzar's troops, after a defence which steeped the wide area in blood; and at the conquest of the city by Titus, thousands fell, within its bounds, by the weapons of the Roman soldiers, or perished in the flames of the third Temple, amidst shrieks from the crowds on Zion, heard even above the roar of strife and of the conflagration.* Jos. Ant., xv. 11, 5.

Chapter 21 | Contents | Chapter 23

Philologos | Bible Prophecy Research | The BPR Reference Guide | Jewish Calendar | About Us