by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

Philologos Religious Online Books

Philologos.org

Chapter 20 | Contents | Chapter 22

Cunningham Geikie D.D.

With a Map of Palestine and Original Illustrations by H. A. Harper

Special Edition

(1887)

I entered the Holy City by the Joppa Gate, which stands near the north-west angle of the walls, rising on the south side from a deep hollow inside the wall, but standing on ground level with the road in all other directions. It is a castle-like building about fifty feet high, with battlemented top, very unfit now, however, to bear guns of even the lightest calibre, for the stones are but slightly held together by the rotten mortar, and, indeed, have fallen down at some spots. Grass grows where the watchman once looked out, and time has for centuries been allowed to play what freaks it pleased. As in many other gates, there is a turn at right angles before you get through—a plan adopted in olden days to help the defence. The front is, perhaps, forty feet across in all; the sides about eighteen feet deep; the entrance, from the city side, is through a comparatively narrow gate, which fits roughly into the lower part of a high pointed arch, filled in with masonry above and at the sides to suit the rickety door. In the bow of the arch, about twenty feet above the ground, is an inscription in Arabic, and on the door itself are a very rude star and crescent, the emblems of Turkish rule. Outside, the Joppa road stretches up a slope, lined for a short distance on the upper side by some shops and houses, including the British Consul's office; an open space spreading out on the other side, covered more or less with the booths of small dealers, donkeys waiting for hire, and a native cafe, of wood, before which numbers of labourers and workmen sit on low stools, smoking water-pipes, at all hours. Eating or drinking they do not indulge in; water-pipes seeming to be all that the cafe supplies.

A low wall, rising from the ditch and overgrown with leaves and stalks, runs along, inside the gate, on the right hand of the Tower of David. On the left the first sample of the domestic architecture of Jerusalem that one meets is a wretched house, about twelve feet high and eight broad, on a line with the left side of the gate, its front showing only decaying plaster, a rough door, and a small window, so high that no one can see through it; the tiled roof broken and moulting. One or two other hovels and a higher serpentine wall, turning hither and thither on its private account, to shut in some wretchedness or other, complete the picture. Camels passing through the gate took up for the moment all its available space as they stalked on, looking, as these creatures always do, straight before them, and meekly following a dark-skinned Arab who strode on in front, in white "kefiyeh" and cotton shirt, with bare legs; a water-bottle in one hand, a cord from the nose of the foremost camel in the other, and a bundle on his back. A gentleman in a fez and striped "abba" sat on the ground, with his back to the gate, behind a modest display of fruit, chiefly oranges, set out on flat dishes and extemporised trays made from old boxes. Beside him stood a brother Jerusalmeite, enjoying the shade of the gate, and looking quite dignified in a turban and flowing brown-and-white "abba" as he indulged in a quiet gossip with the fruit merchant at his feet. Three or four donkeys, unemployed for the moment, were smelling the low limestone wall, or biting each other; a less fortunate member of their race pattered on under a baggy-breeched figure; a donkey-boy was looking at a turbaned purchase who had sat down on nothing, as only Orientals can, and was resting on his feet, his knees at his mouth, as he cheapened the terms on which a lady, sitting in the same attitude on the other side of some native brown unglazed earthenware dishes and jars, was willing to part with these treasures, both carefully using the scanty shadow of the wall during their solemn and protracted negotiations. Two grave turbaned figures stood behind, resting against the parapet in all the delight of idleness. The donkeys, and some pedestrians who had buttonholed each other for a chat, filled up, in a loose way, the space between this side of the street and the opposite, where another fruit merchant had extemporised a rude shade of old matting and branches, propped on a few sticks of all sizes, and dipping sadly in the middle. Under this sat a man on the ground, with a water-bottle at his lips, as I passed, and open palm baskets of fruit on all sides. Near him, and connected with the same establishment, an old man sat on the ground, with his legs, for a wonder, straight out in front, bargaining with a donkey-boy as to how many oranges he could afford to give for a farthing—a transaction which two bearded, turbaned citizens, in flowing robes, were following with rapt attention. Two camels went by, one tied to the other's coarse wooden pack-saddle, both with a large bag on each side, and surmounted by two human figures in "kefiyehs," with stout sticks, and faded linen, seated on the humps of the animals, with their legs crossed above the neck, as the brutes swayed slowly onwards. At every step such Oriental phenomena, human and four-footed, filled the way more numerously, as my horse paced wearily on, past the citadel, down the slope to the hotel where I was to put up.

The population of the city is one of its great attractions; one can never weary of looking at the endless variety of dress and occupation. An open space before the hotel was delightful for the human kaleidoscope it offered. Day by day you could watch kneeling camels waiting to be hired or to receive their loads, and waving lines of men and women, the one in "abbas," the other in the female counterpart, the "izar," sitting on the stones, or on a sack, with their knees on a level with their chins, behind heaps of cauliflowers, lemons, onions, radishes, oranges, and other fruit or vegetables, hoping for customers who seemed never to come. The wall towards the Joppa Gate, and in front of the citadel, which occupied the corner of the open space, was a favourite haunt of lowly tradesfolk. A few short poles resting on the ground and on the top of the low wall formed a frame over which to spread an old mat, laid on a shaky roof of sticks, nailed or tied together, the horizontal poles serving to display all kinds of wares, dangling from them; a few box-tops, or mat baskets, or sacks spread on the ground, letting the public into the secret of the extra stores awaiting their coin. A tempting display of wire, a wooden mouse-trap, a sheaf of ancient umbrellas in various stages of decay, but about to be resuscitated, filled up some yards of wall. An old man, with his back resting against the stones, and a few rags below him for cushion, a white turban on his head, an old brown striped "abba" over some unknown under-garment, and a long pipe in his hand, sat with the gravity of a pasha at the side of three small baskets of lemons, raisins, and figs: his whole stock-in-trade worth in all, perhaps, a shilling. A low rush stool at his side was set for any chance purchaser.

As I passed, a filthy camel swung slowly down the rough stones of the street, with a huge barrel balanced on each side. Jews were numerous in wideawakes, or in flat cloth caps with fur round them, a love lock hanging at each ear; their dress a long black gown over a yellow tunic fitting the body and reaching the feet. A breadseller displayed some questionable brown "scones" on a board, laid on two small boxes; himself seated on a bag on the ground; his outfit, a large white turban, a striped cotton tunic extending to his ankles, and a patched black stuff jacket; all, like himself, the worse for wear. A bead and trinket seller had his wares spread out on a bit of brown sacking, alongside the wall, with a small packing-box before him—his counter by day and his safe at night. Each morning fresh cauliflowers rose in banks and mounds on the two stone steps opposite the hotel, with a passage left in the middle of the street for traffic. A venerable figure with a great white beard, surmounted by a white turban, and set off with a striped "abba," sat near by, cross-legged, on some rags, beside a few fly-blown figs of the year before, not larger than nuts; his scales beside him, as if anyone would ever think of investing in his poor display! Near at hand, another cross-legged patriarch presided over some oranges and lemons, in all the dignity of a white turban, a blue cotton coat reaching to his calves, and an old coloured sash round his waist. Passing in front of him was a knife-grinder, carrying his wheel on his back, ready to set it down when a job offered, and shouting his presence, to attract customers. Water-carriers, in skull-caps or turbans, bare-armed and bare-legged, moved about with black skins full of the precious fluid, which they were taking to houses to empty into the domestic water-jars, sometimes through a hole in the wall; for it is not always reckoned safe to allow a man to enter the kitchen and thus see the other sex in the household.

Well-to-do men occasionally brightened the general air of poverty; one, for example, in a long blue cloth coat lined with fur, a white turban, yellow baggy breeches, a white vest, and a bright-coloured sash. Women with bundles of fagots upon their heads for fuel; ridiculous-looking Armenian females with baggy breeches instead of petticoats; Turkish soldiers in shabby blue uniform; an occasional American, Englishmen, or Continental European; a woman with a child astride her shoulders; some Russian pilgrims, who had, perhaps, walked from Archangel to Constantinople, with fine manly beards, fur, mortar-board-like caps, long warm great-coats, thick boots, or shoes, their legs, where they had not boots over their trousers, tied up with cross-straps, over warm wrappings which served for stockings; beggars with long sticks in their hands, and the oddest mockery of cotton clothing; a peasant with his plough on his shoulder, taking it to the smith to mend or sharpen; camels with huge loads of olive-cuttings, or fagots, for fuel, the driver in a "kefiyeh" sitting aloft over all, with the guiding-rope in one hand and a long pipe in the other—all this was only a sample of the ever-changing spectacle of the street.

The citadel, which rose almost opposite my hotel, is one of the most striking features of the Holy City. It stands on Mount Zion, in the middle of the western side, occupying, with its ditch and walls, about 150 yards from north to south, and about 125 from east to west; another space, seventy-five yards square, being taken up on the south side by the Turkish barracks. Beyond these the splendid garden of the Armenian monastery runs, for another 250 yard, inside the wall; the fortress, barracks, and garden occupying a continuous strip within the wall, a little less than 500 yards in length; the west side, in fact, of Mount Zion. How great a piece this is of the city may be judged by the size of the whole town, omitting the great Temple grounds to the east, now those of the Mosque of Omar. From north to south, it is about 1,200 yards from the Damascus Gate to the Zion Gate, and it is about 700 yards from the Joppa Gate, on the west, to the Temple grounds on the east. Add to this a square of less than 400 yards, joining the north end of the Temple space, and you have the entire city; the area once sacred to the Temple, which also is within the walls, filling up an extra 300 yards or so of breadth, and a length of about 500 yards. The walk round the walls, which, of course, enclose everything—monasteries, gardens, Temple space, citadel, streets, and churches—is about two miles and a half. But it is about three miles and a half round Hyde Park, including Kensington Gardens.*

The western side of the city is slightly higher than the eastern, the ground near the Joppa Gate and on Mount Zion, to the south of it, lying about 2,550 feet above the sea, while the Temple space is 110 feet lower. There is thus a slope to the east in all the streets running thence from the west, although the levels of the ancient city have been greatly modified by the rubbish of war and peace during three thousand years. The Jerusalem of Christ's day lies many feet beneath the present surface, as the London of Roman times is buried well-nigh twenty feet below the streets of to-day. The citadel stands at nearly the highest point of the town, and as it was thus connected originally with the great palace and gardens which Herod created for himself at this point, it is only necessary to imagine the space now covered by the barracks and the Armenian garden as once more occupied by a magnificent pile of buildings and pleasure-grounds, to bring back the aspect of this portion, at least, of the Jerusalem of our Lord's day.* Measured on Baedeker's plan of Jerusalem, and the plan in Murray's Handbook of London, of course only approximately. Robinson makes the circumference of Jerusalem the same as I do.

All remains of Herod's grand structure are buried, however, beneath more than thirty feet of rubbish, except portions of two of the three towers he built on the north side of his grounds. "These huge fortresses," says Josephus, "were formed of great blocks of white stone, so exactly joined that each tower seemed a solid rock." One of them, named after his best-loved but murdered wife, Mariamne, has entirely vanished, but Phasaelus and Hippicus still in part survive. When they guarded the wall, thirty cubits high, which entirely surrounded Herod's palace, with its decorated towers at intervals rising still higher, they must have been imposing in their strength, to judge from the noblest relic they offer—the so-called Tower of David, which seems to have been part of the Phasaelus Tower, or perhaps of the Hippicus, for authorities differ upon the subject. It stands on a great substructure rising, at a slope of about 45o, from the ditch below, with a pathway along the four sides at the top. Above this, the tower itself, for twenty-nine feet, is one solid mass of stone, and then follows the superstructure, formed of various chambers. The masonry of the substructure is of large drafted blocks, many of them ten feet long, with a smooth surface; that of the solid part of the tower has been left without smoothing. Time has dealt hardly with the stone of the superstructure, which is comparatively modern, but even that of the solid base and the substructure is rough with lichens and a waving tangle of all kinds of wall-plants. Still, as one looks up from the street, it seems as if the shock of a battering-ram could have had little effect on the sloping escarpment, or the solid mass over it. Nor would escalade have been easy, if indeed possible, when the masonry was new, so smooth and finely jointed is the whole. Besides other buildings, there are in the citadel grounds five towers, once surrounded by a moat which is now filled up. The outer side of one of these, the second of Herod's three, rises from a deep fosse at the side of the road below the Joppa Gate, as you go down the Valley of Hinnom, and helps one to realise still more forcibly the amazing strength of the ancient portions of these structures.

Desirous to have a view of Jerusalem from a height, I ascended to the top of the Tower of David. The entrance from the open space before it is through a strong but time-eaten and neglected archway, surmounted by pinnacles, the fleurs-de-lis on the top of which, half grown over by grass and rank weeds, show the work of those wondrous builders, the Crusading princes. Half the central archway is built up, leaving open a pointed gate, over which a clumsy wooden ornament represents two crescent moons. On the right is a recess in the wall for the sentries; on the left a side gate; the recess and side gate, alike, arched and small. A rough platform of three rows of stone, ascended by steps, juts out before the recess, and on this a sentinel stands, scimitar or gun in hand—another standing at the centre gate: strong men from some distant part of the empire, perhaps from Kurdistan, perhaps from Asia Minor. Some town dogs lay below the rude bank of stone at the guard-house door, asleep by day, noisy enough by night. A man sat on a rush stool beside the low wall, smoking his water-pipe; a second lay on the ground; a third had a small, low, round table before him, with a few oranges for sale; pending the arrival of a customer, he was gravely sucking the long coiled tube of a water-pipe, or hubble-bubble, holding discourse, in the intervals of breath-taking, with the two gentlemen on the ground near him, or with a fourth who stood, in flowing robes, slippered feet, and turban, propping himself against his stick, a fierce club-like affair. Of course he was bare-legged. In Europe, all four would have been tattered beggars; but they looked quite dignified in Eastern costume. A causeway, slightly raised above the rough cobble stones of the open square, led through the gateway, over the ditch, by a wooden bridge in very poor condition, and originally of carpentry so primitive that it might have been antediluvian, though really Turkish and modern. Stairs on the outside of the great tower led half-way up its height, beyond the solid base, and the rest was scaled by other stairs inside, by no means safe, for the Turk never repairs anything. Round the top is a parapet, through the embrasures of which cannon might be turned on the city, which the position commands. But though there were some guns on the cemented roof, it is a question whether any of them were in a condition to be used, for, like everything else, they were far gone in decay.

The view from this point was very striking. Close at hand to the south, beyond the barracks, were the noble gardens of the Armenian monastery, not only part of the grounds of Herod's palace nearly two thousand years ago, but perhaps of those of David and Solomon's gardens, for these also covered the western top of Mount Zion. One could understand how difficult the victory of Titus must have been, with three such castles to take, for, looking down into the ditch, it seemed as if this one, at least, must have been impregnable before the discovery of gunpowder. It was easy, moreover, to understand how the Egyptian warriors so long withstood, within these strongholds, the Crusaders under Godfrey of Bouillon and his companions. Looking over the houses of the city, the eye was bewildered by the multitude of small domes rising from the flat roofs, to protect the tops of the stone arches below, for the houses are all built arch above arch, wood being scarce and stone plentiful. Of course, everything was old and weather beaten; every wall-top feathered with grass and weeds; the walls unspeakably rude in their masonry; the one or two sloping roofs that showed themselves very woe-begone; everything indeed marking a city far sunk in decay, and at best only holding together while it could, with no prospect of returning to vigorous life. A party of men were on a flat roof near, smoking; a poor little child, very likely a slave, standing on one side of the low dome with a tray and coffee-cups on the ground beside him, and a man leaning against the other side of the dome, as he played with his water-pipe. A slight puff of kitchen-smoke here and there showed where the small fires used for Oriental cookery were alight. Several parapets had triangles of open clay cylinders in them, for look-out holes and air, as is common in Eastern towns. On one roof some clothes were drying. A solitary palm-tree rose aloft out of a court. On one house-top a flat awning of mats had been raised on poles, and under this were a group of idlers. Windows seemed almost absent, for the Oriental has no idea of ventilation. He never has windows on the ground-floor, and even those higher up are either miserably small openings in the wall, or rough projecting woodwork, which leaves only a small place for lattices. There were, of course, some better houses; but, as a whole, one might fancy himself to be looking down on an East End district of London. Few houses were more than two storeys high.

Beyond the city nature redeems the sordid outlook over these miserable human abodes. The hills rise on every side, recalling the words of the Psalmist, who, from some such eminence as that on which I stood, had cried out, "As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about His people from henceforth even for ever" (Psa 125:2). On some such point of vantage, also, the prophet had imagined himself set as a warder, when he saw with the eye of the spirit, as if before him, the restoration of the city, after it had been laid desolate by the Chaldæans, and cried aloud at the prophetic sight of the herald bringing the announcement that Jehovah was returning to Zion, Himself the leader of Israel from captivity, "How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of Him that bringeth good tidings, that publisheth peace, that bringeth good tidings of good, that publisheth salvation; that saith unto Zion, Thy God reigneth! The voice of thy watchmen! they lift up the voice, together do they sing; for they shall see eye to eye, now the Lord returneth to Zion" (Isa 52:7,8).

The four hills, north, east, and south, on which the city is built, could, more or less, be traced beneath by deeper or slighter depressions of the view. The hill on the north,on which the huge copper dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre rises between two Mahommedan minarets, continues to mount with a very gradual ascent beyond the walls, presenting the only easy approach to Jerusalem from any side, and hence offering the point from which hostile armies have always assailed it. It was from this plateau that Godfrey de Bouillon stormed the city, and on the height 600 yards north-west of the Joppa Gate, where now rise the buildings of the Russian Hospice, the tents of Titus once stood.

On the north of the Temple grounds, and thus at the north-east corner of the city, lies the hill Bezetha, part of the Mahommedan quarter of Jerusalem, the rest of which extends, on the north, to the Damascus Gate, and, thence, down to the street which runs east from the Joppa Gate. The Temple space is thus guarded by Mahommedans at its different entrances. The corner between the Damascus Gate and the Joppa Gate, on the north-west, is assigned to the Roman Catholics and the Greeks, and the rest, from the south side of the street, running east from the Joppa Gate, is divided between the Armenians and the Jews, these latter having the consolation of knowing that their district borders, in part, the wall of their deeply-loved Mount Moriah. Directly east, and slightly lower, lay the wide open area, of somewhat less than thirty-five acres, where once stood the Temple.* On the south-west stretched out Mount Zion, the highest and oldest part of the city; that part which David wrested from the Jebusites, and made his capital. The city wall at one time enclosed the whole of the hill; but it now runs, south-west, across it, leaving on the spot where, perhaps, once stood the palace of Solomon, an open space, on which are the Christian cemetery and the Protestant schools. Part, however, is still open ground, where the peasant drives his plough over the wreck of the City of David, fulfilling, even to this day, the words of Micah, that Zion would be ploughed as a field (Micah 3:12). But the most extensive view was to the south-east, where the deep blue of the Dead Sea, the pinkish-yellow hills of Moab, and the sea of hills in the wilderness of Judæa and beyond it, lay within the horizon. Most noticeable of all, just outside Jerusalem, sloping upwards to the east, the noble form of the Mount of Olives rose more than 200 feet above the Temple enclosure**—that is, above the summit of the ancient hill of Moriah.

The back windows of the hotel looked down into a great pool 144 feet broad, and 240 feet long, but not deep; the bottom, of rock, covered with cement. It was well filled with water, which comes, during the rainy season only, by the surface drain, or gutter, leading from the "Upper Pool" in the Mahommedan cemetery, on the high ground about 600 yards west of the Joppa Gate, from which point it runs underground. This seems to be the reservoir which Hezekiah constructed when he "made a pool and a conduit, and stopped the upper water-course of Gihon, and brought it straight down to the west side of the city of David" (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chron 32:30), and "digged the hard rock with iron, and made wells for water" (Ecclus 48:17). Its south side is separated by only a line of houses from the street; the Coptic monastery is at its northern end, and at a little distance to the north-west is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with its high dome and its unfinished tower. The houses bordering the pool are of all heights; one with a sloping roof and a projecting rickety balcony, just above the water; another, roofed in the same way, but more than a storey higher, with a square wooden chamber, supported by slanting beams, built out, partly, it would seem, to let the inmates drop a bucket through a hole in the floor, to the water. A frame of poles covered one flat roof, to serve as support for a mat awning in the hot months, a wooden railing acting as parapet on the pool side; projecting windows, larger or smaller, were frequent, one with boxes of flowers outside; and, of course, the roofs had their usual proportion of men idling over their pipes. As everywhere else, the walls round the pool were thick with naturally-sown wall-plants, the very emblem of a neglect which extended, perhaps, over centuries. The pool is capable of containing about 3,000,000 gallons of water, but it is in very bad repair. As to cleaning it out, nothing so revolutionary ever entered the brain of a Jerusalemite. The bottom is deep with the black mud of decayed leaves and vegetation, and one corner is a cesspool of the worst description. The water is said to be used only for household washing, but the poorer people frequently drink it in summer, when water is scarce, though it is then at its worst, having lain stagnant, perhaps for months, since the rains.* It is an irregular parallelogram, measuring on the west 536 yards; on the east, 512 yards; on the north, 348 yards; on the south, 309 yards.

** The respective heights are 2,440 feet and 2,663 feet.

A few steps down David Street—the lane leading east and west from the Joppa Gate to the Temple enclosure—brings you to Christian Street, which runs north; and close to this, on the under side, is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But what would any one think of the street called after the hero-king of Israel, if suddenly set down at the end of it! It is a lane rather than a street, with houses, for the most part only two storeys high, on each side, the lower one being given up to shops, if you can call such dens by so respectable a name. Over the doors a continuous narrow verandah of wood, built at a slant into the houses, gives shade to the goods, but when it was put up or repaired in any way is an insoluble historical problem. Its condition, therefore, may be easily fancied. The causeway of the street is equally astonishing, for even a donkey, most sure-footed of animals, stops, puts its nose to the ground, and makes careful calculations as to the safe disposition of its feet, before it will trust them to an advance. No wonder there are no people in the streets after dark; without a lantern they would infallibly sprain their ankles, or break a leg, each time they were rash enough to venture out. But during the day the stream of many-coloured life flows through this central artery of the Holy City in a variety to be found, perhaps, nowhere else. The open space at the head of it, before the Tower of David, is always thronged, as I have tried to describe, but every time you look at it, or look from it down the Street of David, the scene is different. As soon as light breaks, strings of camels, led and ridden by dark-faced Bedouins, begin to swing through the Joppa Gate to this common centre—the largest open space in the city. Women from Bethlehem, with dresses set off with blue, red, or yellow, and unveiled faces, though they have veils over their shoulders; Mahommedan women in blue gowns, which might be called by a humbler name if they were white: their eyes, the only part of their faces to be seen, looking larger than they are from the black pigment with which the edges of the eyelids are darkened; soldiers in a variety of strange uniforms; trains of donkeys with vegetables; a stray Arab, in wild desert costume, with red boots, on a horse with a red saddle, his spear, more than twelve feet long, in his hand; women in white "izars," which are coverings put on over the dress from head to foot, puffing out like balloons as the wearer advances; a half-naked dervish holding out his tin pan for alms, which he asks in the name of the All-merciful; a company of Turkish soldiers, in poverty-stricken uniforms, but strong fellows all, following their band, which plays only short, unmeaning flourishes, in the French style; Russian pilgrims; Jews of every nationality; residents from all Occidental climes;—all these, with many others, pour on through the narrow gullet of David Street, or rest for a time in the market space. You may even see a family of gipsies encamped there, under their low black tent; for, within wide limits, every one does as he likes in the East.

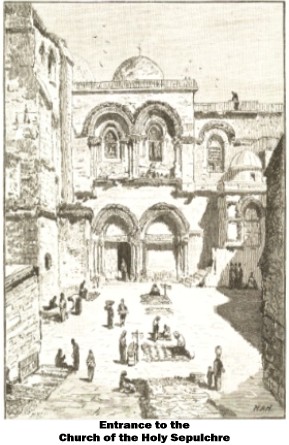

Christian Street is specially the quarter of the Christian tailors, shoemakers, and other craftsmen. Passing about 200 steps along it, we come to a very narrow street on the right, running downhill, with a frightful causeway. Turning

into this, you presently come to a few steps on the left, which your donkey, if you have one, makes no difficulty in descending, and you are then in the open paved space before the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This is a favourite haunt of Bethlehemite sellers of mementoes in mother-of-pearl and olive-wood, which, with other trifles, are exposed on the pavement. At festival times the throng in this spot is curious in the extreme. Men and women, children and the very old, priests and laymen from every country, repeat the spectacle and the Babel-like confusion of tongues seen and heard of old in this very city on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:8-11). The only entrance to the church is on the southern side, and it was shut when I reached it, but a gift to the door-keeper having turned the key, I entered. On each side of the quadrangle are chapels, Armenian, Coptic, and Greek, the last pretending to be the place where Abraham was about to offer up Isaac. The front of the great church itself is impressive from its evident antiquity. There were originally two round-arched gateways, but that on the right is built up, as is also the upper part of the other. Above these gateways are two arches of the same size and style, deeply sunk, in which, within receding masonry, once elegantly carved, are two round-topped windows of comparatively small size (about ten feet by six). On a ledge below them, where the pillars of the arches begin, some tasteful monk had put various pots of flowers, the short rough ladder by which he had descended from the window-sill remaining where he left it. He had forgotten the poor blossoms, however, and want of water had told sadly on them. Over the two window-arches, which, with their ornamentation, reach nearly to the top of the church wall, is a square railing, enclosing

the dome, which, itself, may well be regarded as worth looking at, since a dispute as to its repair was the ostensible cause of the Crimean War, and, thus, of the death of many thousands of men who never heard of the church in their lives. A window, as large as the others and on the same line, but without the imposing arch, disfigured moreover by a frame of thick iron cross-bars, stands at the right, outside the central facade; these three, about forty feet above the ground, being the only windows in front of the church, so far as is seen from the forecourt. The whole front dates from the twelfth century, when the Crusaders remodelled the building. The influence of the French art of that day is seen in the close resemblance of the ornamentation to that of some churches in Normandy. Indeed, a fine carving over one of the doors, representing Christ's entry into Jerusalem, was probably sent from France.

Christian Street is specially the quarter of the Christian tailors, shoemakers, and other craftsmen. Passing about 200 steps along it, we come to a very narrow street on the right, running downhill, with a frightful causeway. Turning

into this, you presently come to a few steps on the left, which your donkey, if you have one, makes no difficulty in descending, and you are then in the open paved space before the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This is a favourite haunt of Bethlehemite sellers of mementoes in mother-of-pearl and olive-wood, which, with other trifles, are exposed on the pavement. At festival times the throng in this spot is curious in the extreme. Men and women, children and the very old, priests and laymen from every country, repeat the spectacle and the Babel-like confusion of tongues seen and heard of old in this very city on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:8-11). The only entrance to the church is on the southern side, and it was shut when I reached it, but a gift to the door-keeper having turned the key, I entered. On each side of the quadrangle are chapels, Armenian, Coptic, and Greek, the last pretending to be the place where Abraham was about to offer up Isaac. The front of the great church itself is impressive from its evident antiquity. There were originally two round-arched gateways, but that on the right is built up, as is also the upper part of the other. Above these gateways are two arches of the same size and style, deeply sunk, in which, within receding masonry, once elegantly carved, are two round-topped windows of comparatively small size (about ten feet by six). On a ledge below them, where the pillars of the arches begin, some tasteful monk had put various pots of flowers, the short rough ladder by which he had descended from the window-sill remaining where he left it. He had forgotten the poor blossoms, however, and want of water had told sadly on them. Over the two window-arches, which, with their ornamentation, reach nearly to the top of the church wall, is a square railing, enclosing

the dome, which, itself, may well be regarded as worth looking at, since a dispute as to its repair was the ostensible cause of the Crimean War, and, thus, of the death of many thousands of men who never heard of the church in their lives. A window, as large as the others and on the same line, but without the imposing arch, disfigured moreover by a frame of thick iron cross-bars, stands at the right, outside the central facade; these three, about forty feet above the ground, being the only windows in front of the church, so far as is seen from the forecourt. The whole front dates from the twelfth century, when the Crusaders remodelled the building. The influence of the French art of that day is seen in the close resemblance of the ornamentation to that of some churches in Normandy. Indeed, a fine carving over one of the doors, representing Christ's entry into Jerusalem, was probably sent from France.

Just inside the door a guard of Turkish soldiers, keep there to secure peace between the rival Christian sects, jars on the feelings, as being sadly out of place amid such surroundings, however necessary. To see them lying or sitting on their mats, smoking or sipping coffee, is by no means pleasant, but after all it is better to have quiet at even this price than such riots and bloodshed as have disgraced the church at various times. Immediately before you is the "stone of unction," said to mark the spot on which our Lord's body was laid in preparation for burial, after being anointed. It is a large slab of limestone, and has at least the merit of having lain there for seven or eight hundred years, as an object of veneration to poor simple pilgrims. A few steps to the left is the place where, as they tell us, the women stood during the Anointing, and from this you pass at once, still keeping to the left, into the great round western end of the church—the model of all the circular churches of Europe—under the famous dome, which rests on eighteen pillars, with windows round the circle from which the dome springs. In the centre of this space, which is sixty-seven feet across, is the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre, about twenty-six feet long and eighteen feet wide, a tasteless structure of reddish limestone, like marble, decorated all along the top with gilt nosegays and modern pictures, and its front ablaze with countless lamps. Inside, it is divided into two parts: the one marking, as is maintained, the spot where the angels stood at the Resurrection; the other believed to contain the sepulchre of Christ. Huge marble candlesticks, with gigantic wax candles, lighted only on high-days, stand before the Chapel of the Angels, on entering which pilgrims take off their shoes, before treading on ground so sacred. A hole on each side of the entrance shows the scene of one of the few mock-miracles still played off on human credulity, for through them the "Holy Fire," said to be sent from heaven, is given out, every Greek Easter, amidst a tumult and pressure of the outside crowd which seems to threaten numerous deaths. On the evening before the day of the Fire, every spot inside the church is densely packed with worshippers, sleeping as they stand, in weary expectation of the approaching event, or, if awake, crossing their breasts, sighing aloud, and, if possible, prostrating themselves on the floor. The next forenoon, a Turkish guard, in double line, opens a passage round the sepulchre, broad enough for three men to pass through abreast, and outside this armed wall the crowd, pressed into the smallest possible space, extends from the wall of the Rotunda to that of the Sepulchre Chapel. How so many human beings get into so small a standing-ground seems, itself, miraculous. Captain Conder's description of what next ensues is so vivid that I follow it.* "The sunlight came down from above, on the north side, where the Greeks were gathered, while on the south all was in shadow," though it was noon. "The mellow grey of the marble was lit up, and a white centre of light was formed by the caps, shirts, and veils of the native Christians. A narrow cross-lane was made at the Fire-hole on the north side," where "six herculean guardians, in jerseys, and with handkerchiefs round their heads, kept watch—the only figures plainly distinguishable among the masses."

The pilgrims, who represented every country of Eastern Christendom—Armenians, Copts, Abyssinians, Russians, Syrians, Arabs, each race by itself, in its national dress, marked by its colours as well as its style; not a few women among them, some with small babies in their arms, wailing above the hubbub of multitudinous tongues in many languages—had been standing in their places for at least ten hours, yet they showed no signs of weariness. Every face was turned to the Fire-hole; the only distraction arising when great pewter cans of water were brought round by the charity of the priests. Patient and stolid, the Russians and Armenians stood quietly, each pilgrim holding aloft in his hand, to keep them safe, a bunch of, perhaps, a dozen candles, to light at the "Fire" when it should appear. The Egyptians sat silent and motionless. The Greek Christians, mostly Syrians by birth, were restless, on the other hand, with hysterical excitement. Occasionally, one of them would struggle up to the shoulders of his neighbours, and be pushed over the heads of the crowd, towards the front. Chants repeated by hundreds of voices, in perfect tune, were frequently raised by individual leaders; among them—"This is the Tomb of our Lord"; "God help the Sultan"; "O Jews, O Jews, your feast is a feast of apes"; "The Christ is given us; with His blood He bought us. We celebrate the day, and the Jews bewail"; "The seventh is the Fire and our feast, and this is the Tomb of our Lord."* Tent Work in Palestine, p. 175.

Amidst all the wild confusion the patience of the soldiery was admirable, though at times there seemed danger. A lash from a thick hippopotamus-hide whip carried by the colonel, however, instantly administered where there seemed risk of disturbance, restored peace as by magic. About one o'clock the natives of Jerusalem arrived, bursting in suddenly, and surging along the narrow lane; many of them stripped to their vests and drawers. To clear the line once more, after this irruption of a second crowd, was difficult, but it was at las done, amidst loud shouts of "This is the Tomb of our Lord," repeated over and over, with wondrous rapidity. The Rotunda now contained in its little circle of sixty-seven feet diameter, from which the space occupied by the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre must be deducted, about 2,000 persons; and the whole church, perhaps, 10,000; but at last the chant of the priests was heard in the Greek church, and the procession had begun. First came very shabby banners; the crosses, above them, bent on one side. The old Patriarch looked frightened, and shuffled along, with a dignitary on both sides carrying each a great silver globe, with holes in it, for the Fire which was to be put inside. Now rose a chorus of voices from the men, and shrill cries from the women; then all was still. Two priests stood, bareheaded, by the Fire-hole, protected by the gigantic guardians at their side.

Suddenly a great lighted torch was in their hands, passed from the Patriarch within, and with this, the two priests, surrounded by a body-guard of gigantic men, turned to the crowd; they and their guard trampling like furies through it. In a moment the thin line of soldiers was lost in the two great waves of human beings, who pressed from each side to the torch, which blazed over them, now high, now low, as it slowly made its way to the outside of the church, where a horseman sat, ready to rush off with it to Bethlehem. In its slow and troubled advance, hundreds of hands, with candles, were thrust out towards it, but none could be lighted in such a rocking commotion. Presently, however, other lighted torches were passed out of the Fire-hole, and from these the pilgrims, in eager excitement, more and more widely succeeded in kindling their tapers, but woe to the owner of the one first lit! it was snatched from him, and extinguished by a dozen others, thrust into it. Delicate women and old men fought like furies; long black turbans flew off uncoiled, and what became of the babies who can tell? A wild storm of excitement raged, as the lights spread over the whole church, like a sea of fire, extending to the galleries and choir. A stalwart negro, struggling and charging like a mad bull, ran round the church, followed by writhing arms seeking to light their tapers from his; then, as they succeeded in doing so, some might be seen bathing in the flame, and singeing their clothes in it, or dropping wax over themselves as a memorial, or even eating it. A gorgeous procession closed the whole ceremony; all the splendour of jewelled crosses, magnificent vestments, and every accessory of ecclesiastical pomp, contributing to its effect.

A religious phenomenon so strange as this yearly spectacle is nowhere else to be found. Dean Stanley's account of it supplies some additional touches, and brings it not less vividly before us. "The Chapel of the Sepulchre,"* he says, "rises from a dense mass of pilgrims, who sit or stand, wedged round it; whilst round them, and beneath another equally dense mass, which goes round the walls of the church itself, a lane is formed by two lines, or rather two circles, of Turkish soldiers, stationed to keep order...About noon this circular lane is suddenly broken through by a tangled group, rushing violently round, till they are caught by one of the Turkish soldiers. It seems to be the belief of the Arab Greeks that unless they run round the sepulchre a certain number of times, the Fire will not come. Possibly, also, there is some strange reminiscence of the funeral games and races round the tomb of an ancient chief. Accordingly, the night before, and from this time forward, for two hours, a succession of gambols takes place, which an Englishman can only compare to a mixture of prisoner's base, football, and leap-frog, round and round the Holy Sepulchre. First, he sees these tangled masses of twenty, thirty, fifty men, starting in a run, catching hold of each other, lifting one of themselves on their shoulders, sometimes on their heads, and rushing on with him till he leaps off, and some one else succeeds; some of them dressed in sheepskins, some almost naked; one usually preceding the rest, as a fugleman, clapping his hands, to which they respond in like manner, adding also wild howls, of which the chief burden is, 'This is the Tomb of Jesus Christ—God save the Sultan'; 'Jesus Christ has redeemed us.' What begins in the lesser groups, soon grows in magnitude and extent, till, at last, the whole of the circle between the troops is continuously occupied by a race, a whirl, a torrent, of these wild figures, wheeling round the sepulchre. Gradually the frenzy subsides or is checked; the course is cleared, and out of the Greek church, on the east of the Rotunda, a long procession with embroidered banners, supplying in their ritual the want of images, begins to defile round the sepulchre.

"From this moment the excitement, which has before been confined to the runners and dancers, becomes universal. Hedged in by the soldiers, the two huge masses of pilgrims still remain in their places, all joining, however, in a wild succession of yells, through which are caught, from time to time, strangely, almost affectingly mingled, the chants of the procession. Thrice the procession paces round; at the third time, the two lines of Turkish soldiers join and fall in behind. One great movement sways the multitude from side to side. The crisis of the day is now approaching. The presence of the Turks is believed to prevent the descent of the Fire, and at this point they are driven, or consent to be driven, out of the church. In a moment, the confusion, as of a battle and a victory, pervades the church. In every direction the raging mob bursts in upon the troops, who pour out of the church at the south-east corner—the procession is broken through, the banners stagger and waver. They stagger, and waver, and fall, amidst the flight of priests, bishops, and standard-bearers, hither and thither, before the tremendous rush. In one small but compact band, the Bishop, who represents the Patriarch, is hurried to the Chapel of the Sepulchre, and the door is closed behind him. The whole church is now one heaving sea of heads, resounding with an uproar which can be compared to nothing less than that of the Guildhall of London at a nomination for the City. One vacant space alone is left, a narrow lane from the aperture on the north side of the chapel, to the wall of the church. By the aperture itself stands a priest, to catch the Fire; on each side of the lane, as far as the eye can reach, hundreds of bare arms are stretched out like the branches of a leafless forest—like the branches of a forest quivering in some violent tempest.* Sinai and Palestine, p. 460.

"In earlier and bolder times the expectation of the Divine Presence was, at this juncture, raised to a still higher pitch by the appearance of a dove, hovering above the cupola of the chapel, to indicate the visible descent of the Holy Ghost. This has now been discontinued, but the belief still continues. Silent—awfully silent—in the midst of this frantic uproar, stands the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. At last the moment comes. A bright flame, as of burning wood, appears within the hole, kindled by the Bishop within—but, as every pilgrim believes, the light of the descent of God Himself upon the Holy Tomb. Any distinct feature or incident is lost in the universal whirl of excitement which envelops the church, as, slowly, gradually, the fire spreads from hand to hand, from taper to taper, through that vast multitude—till, at last, the whole edifice, from gallery to gallery, and through the area below, is one wide blaze of thousands of burning candles...It is now that a mounted horseman, stationed at the gates of the church, gallops off with a lighted taper, to communicate the Sacred Fire to the lamps of the Greek church in the convent at Bethlehem. It is now that the great rush, to escape from the rolling smoke and the suffocating heat, and to carry the lighted tapers into the streets and houses of Jerusalem, through the one entrance to the church, leads at times to the violent pressure which, in 1834, cost the lives of hundreds. For a short time the pilgrims run to and fro, rubbing their faces and breasts against the fire, to attest its supposed harmlessness. But the wild enthusiasm terminates from the moment that the fire is communicated. Such is the Greek Easter."

But we must return to the chapel. In the centre, cased in marble, stands what is called a piece of the stone rolled away by the angels; and at the western end, entered by a low doorway, is the reputed tomb-chamber of our Lord, a very small spot, for it is only six feet wide, a few inches longer, and very low. It seems to belie its claim to be a burial-place by the glittering marble with which it is cased, but it is solemnly beautiful in the soft light of forty-three gold and silver lamps, hung from chains and shining through red, yellow, and green glass; the colours marking the sects to which the lamps belong: thirteen each for Franciscans, Greeks, and Armenians, and four for the Copts. The tomb itself is a raised table, two feet high, three feet wide, and over six feet long, the top of it serving as an altar, over which the darkness is only relieved by the dim lamps. Due east from the Rotunda is the Greek nave, closed, at the far end, by a magnificent screen. A short column in the floor, which is otherwise unoccupied, marks what was anciently believed to be "the centre of the world"; for has not Ezekiel said, "This is Jerusalem; I have set it in the midst of the nations and countries, that are round about her"? (Eze 5:5). Garlands of lamps, gilded thrones for the Bishop and Patriarch, and the lofty screen, towering up to the roof, carved with figures in low relief, row above row; the side walls set off with panels, in which dark pictures are framed; huge marble candlesticks, two of them eight feet high,—all this, seen in the rich light of purple and other coloured lamps, makes up an effect which is very imposing. At the western extremity of the so-called sepulchre, but attached to it from the outside, is a little wooden chapel, the only part of the church allotted to the poor Copts; and further west, but parted from the sepulchre itself, is the still poorer chapel of the still poorer Syrians, happy in their poverty, however, from its having probably been the means of saving from marble and decoration the so-called tombs of Joseph and Nicodemus, which lie in their precincts, and in which rests the chief evidence of the genuineness of the whole site,* for it is certain that they, at least, are natural caves in the rock.

It would be idle to dwell on the multitudinous sacred places gathered by monkish ingenuity under the one roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and which must weary the patience of the pilgrims, however fervent. Two spots only deserve special notice. On the east of the whole building, from behind the Greek choir, a staircase of twenty-nine steps leads down to the Chapel of St. Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine, who in the year AD 326, at the age of nearly eighty, visited Palestine, and caused churches to be erected at Bethlehem, where Christ was born, and on the Mount of Olives, from some part of which He ascended to heaven. Nothing is said till the century after her death about her discovering the Holy Sepulchre, or building a church on the spot, but legend and pious fraud had by that time created the story of the "Invention (or Finding) of the Cross." In a simpler form, the chapel has been ascribed to Constantine himself, who, it is affirmed by a contemporary,* caused the earth under which the enemies of Christianity were said to have buried the Holy Sepulchre to be removed, and built a church over it. Robinson, who gives a full quotation of the authorities on the subject,** thinks there is hardly any fact of history better accredited than the alleged discovery of what is called the true cross. Thus, Cyril, Bishop of Jerusalem from AD 348 onwards, only about twenty years after the event, frequently speaks of his preaching in the church raised by Constantine to commemorate it, and expressly mentions the finding of the cross, under that emperor, and its existence in his own day. Jerome also, in AD 385, relates that in Jerusalem, Paula, his disciple, not only performed her devotions in the Holy Sepulchre, but prostrated herself before the cross in adoration. But, though a cross seems to have really existed, and is said to have been found underground, how easy would deception have been in such a case, and how improbable that any cross should have lain buried for 300 years! The upright beam of such instruments of death, moreover, was a fixture on which fresh cross-pieces were nailed for each sufferer, so that identification of a whole cross as that on which Christ died seems beyond possibility. Besides, the crucifixion is expressly said to have taken place outside the city (John 19:17,20; Mark 15:20; Heb 12:12,13), and this the present site never was. The Chapel of St. Helena, therefore, and the other holy places connected with it, however venerable, are in no degree vouchers for the amazing stories associated with them.* Sinai and Palestine, p. 460.

It is very striking to come upon a vaulted church, with high arches, carved pillars, glittering strings of lamps, exquisite screens, and large sacred pillars, so far underground. But there is still another below it. Thirteen steps more lead to the "Chapel of the Finding of the Cross," which is either a cavern in the rock artificially enlarged, or an ancient cistern, about twenty-four feet long, nearly as wide, and sixteen feet high, paved with stone. It contains an altar, and a large portrait of the Empress Helena, but is so dark that candles must be lighted to see either. This was the place, says tradition, where the three crosses of Calvary were found; the one on which our Saviour died being discovered by taking the three to the bedside of a noble lady afflicted with incurable illness, which resisted the touch of two, but left her at once when the third was brought near.* Eusebius, Vit. Const., iii. 25-40.

** Bib. Researches, ii. 12-16.

Remounting the steps, you are led by a stair from the Greek choir to what is said to be Golgotha, or Mount Calvary, now consecrated by three chapels of different sects, the floor being fourteen and a half feet above that of the church below. An opening, faced with silver, shows the spot where the cross is said to have been sunk in the rock, and less than five feet from it is a long brass open-work slide, over a cleft in the rock which is about six inches deep, but is supposed by the pilgrims to reach to the centre of the earth. This is said to mark the rending of the rocks at the Crucifixion. But there is an air of unreality over the whole scene, with its gorgeous decorations of lamps, mosaics, pictures, and gilding; nor could I feel more than the gratification of my curiosity in the midst of such a monstrous aggregation of wonders. Faith evaporates when it finds so many demands made upon it—when it is assured that within a few yards of each other are the scene of Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac; that of the appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene; the stone of anointing; the spot where the woman stood at the solemn preparation for the tomb; the place where the angels stood at the Resurrection; the very tomb of our Lord; the tombs of Joseph and Nicodemus; the column to which Christ was bound when He was scourged; His prison; the scene of the parting of the raiment; of the crowning with thorns; of the actual crucifixion; of the rending of the rocks; of the finding of the true cross; of the burial-place of Adam, under the spot where the cross afterwards rose; the tree in which the goat offered instead of Isaac was caught, and much else.

Chapter 20 | Contents | Chapter 22

Philologos | Bible Prophecy Research | The BPR Reference Guide | Jewish Calendar | About Us