|

Chapter 9 | Table

of Contents | Chapter 11

The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah

Alfred Edersheim

1883

Book V

THE CROSS AND THE CROWN

Chapter 10

THE PASCHAL SUPPER

THE INSTITUTION OF THE LORD'S SUPPER

(St. Matthew 26:17-19; St. Mark 14:12-16;

St. Luke 22:7-13; St. John 13:1; St. Matt. 26:20; St. Mark

14:17; St. Luke 22:14-16; St. Luke 22:24-30; St. Luke 22:17,18; St. John 13:2-20; St. Matthew 26:21-24; St. Mark 14:18-21;

St. Luke 22:21-23; St. John 13:21-26; St. Matthew 26:25; St.

John 13:26-38; St. Matthew 26:26-29; St. Mark 14:22-25; St.

Luke 22:19,20.)

THE period designated as 'between the two evenings,'1

when the Paschal Lamb was to be slain, was past. There can be no question that,

in the time of Christ, it was understood to refer to the interval between the

commencement of the sun's decline and what was reckoned as the hour of his

final disappearance (about 6 P.M.). The first three stars had become visible,

and the threefold blast of the Silver Trumpets from the Temple-Mount rang it

out to Jerusalem and far away, that the Pascha had once more commenced. In the

festively-lit 'Upper Chamber' of St. Mark's house the Master and the Twelve

were now gathered. Was this place of Christ's last, also that of the Church's

first, entertainment; that, where the Holy Supper was instituted with the

Apostles, also that, where it was afterwards first partaken of by the Church;

the Chamber where He last tarried with them before His Death, that in which He

first appeared to them after His Resurrection; that, also, in which the Holy

Ghost was poured out, even as (if the Last Supper was in the house of Mark) it

undoubtedly was that in which the Church was at first wont to gather for common

prayer?2 We know

not, and can only venture to suggest, deeply soul-stirring as such thoughts and

associations are.

1. Ex.

xii. 6; Lev. xxiii.5; Numb. ix. 3, 5.

2. Acts

xii. 12, 25.

So far as appears, or we have reason to infer, this Passover

was the only sacrifice ever offered by Jesus Himself. We remember indeed, the

first sacrifice of the Virgin-Mother at her Purification. But that was hers.

If Christ was in Jerusalem at any Passover before His Public Ministry began, He

would, of course, have been a guest at some table, not the Head of a Company

(which must consist of at least ten persons). Hence, He would not have been the

offerer of the Paschal lamb. And of the three Passovers since His Public

Ministry had begun, at the first His Twelve Apostles had not been gathered,3

so that He could not have appeared as the Head of a Company; while at the

second He was not in Jerusalem but in the utmost parts of Galilee, in the

borderland of Tyre and Sidon, where, of course, no sacrifice could be brought.4

Thus, the first, the last, the only sacrifice which Jesus offered was that in

which, symbolically, He offered Himself. Again, the only sacrifice which He

brought is that connected with the Institution of His Holy Supper; even as the

only purification to which He submitted was when, in His Baptism, He

'sanctified water to the mystical washing away of sin.' But what additional

meaning does this give to the words which He spake to the Twelve as He sat down

with them to the Supper: 'With desire have I desired to eat this Pascha with

you before I suffer.'

3. St.

John ii. 13.

4. St.

Matt. xv. 21, &c.

And, in truth, as we think of it, we can understand not only

why the Lord could not have offered any other Sacrifice, but that it was most

fitting He should have offered this one Pascha, partaken of its commemorative

Supper, and connected His own New Institution with that to which this Supper

pointed. This joining of the Old with the New, the one symbolic Sacrifice which

He offered with the One Real Sacrifice, the feast on the sacrifice with that

other Feast upon the One Sacrifice, seems to cast light on the words with which

He followed the expression of His longing to eat that one Pascha with them: 'I

say unto you, I will not eat any more5

thereof,6 until it be fulfilled in the Kingdom of

God.' And has it not been so, that this His last Pascha is connected with that

other Feast in which He is ever present with His Church, not only as its Food

but as its Host, as both the Pascha and He Who dispenses it? With a Sacrament

did Jesus begin His Ministry: it was that of separation and consecration in

Baptism. With a second Sacrament did He close His Ministry: it was that of

gathering together and fellowship in the Lord's Supper. Both were into His

Death: yet not as something that had power over Him, but as a Death that has

been followed by the Resurrection. For, if in Baptism we are buried with Him,

we also rise with Him; and if in the Holy Supper we remember His Death, it is

as that of Him Who is risen again - and if we show forth that Death, it is

until He come again. And so this Supper, also, points forward to the Great

Supper at the final consummation of His Kingdom.

5. We

prefer retaining this in the text.

6. Such

would still be the meaning, even if the accusative 'it' were regarded as the

better reading.

Only one Sacrifice did the Lord offer. We are not thinking now

of the significant Jewish legend, which connected almost every great event and

deliverance in Israel with the Night of the Passover. But the Pascha was,

indeed, a Sacrifice, yet one distinct from all others. It was not of the Law,

for it was instituted before the Law had been given or the Covenant ratified by

blood; nay, in a sense it was the cause and the foundation of all the Levitical

Sacrifices and of the Covenant itself. And it could not be classed with either

one or the other of the various kinds of sacrifices, but rather combined them

all, and yet differed from them all. Just as the Priesthood of Christ was real,

yet not after the order of Aaron, so was the Sacrifice of Christ real, yet not

after the order of Levitical sacrifices but after that of the Passover. And as

in the Paschal Supper all Israel were gathered around the Paschal Lamb in

commemoration of the past, in celebration of the present, in anticipation of

the future, and in fellowship in the Lamb, so has the Church been ever since

gathered together around its better fulfilment in the Kingdom of God.

It is difficult to decide how much, not only of the present

ceremonial, but even of the Rubric for the Paschal Supper, as contained in the

oldest Jewish Documents, may have been obligatory at the time of Christ.

Ceremonialism rapidly develops, too often in proportion to the absence of

spiritual life. Probably in the earlier days, even as the ceremonies were

simpler, so more latitude may have been left in their observance, provided that

the main points in the ritual were kept in view. We may take it, that, as

prescribed, all would appear at the Paschal Supper in festive array. We also

know, that, as the Jewish Law directed, they reclined on pillows around a low

table, each resting on his left hand, so as to leave the right free. But

ancient Jewish usage casts a strange light on the painful scene with which the

Supper opened. Sadly humiliating as it reads, and almost incredible as it

seems, the Supper began with 'a contention among them, which of them should be

accounted to be greatest.' We can have no doubt that its occasion was the order

in which they should occupy places at the table. We know that this was subject

of contention among the Pharisees, and that they claimed to be seated according

to their rank.7

A similar feeling now appeared, alas! in the circle of the disciples and at the

Last Supper of the Lord. Even if we had not further indications of it, we

should instinctively associate such a strife with the presence of Judas. St.

John seems to refer to it, at least indirectly, when he opens his narrative

with this notice: 'And during supper, the devil having already cast it

into his heart, that Judas Iscariot, the son of Simon, shall betray Him.'8

For, although the words form a general introduction to what follows, and refer

to the entrance of Satan into the heart of Judas on the previous afternoon,

when he sold his Master to the Sanhedrists, they are not without special

significance as place in connection with the Supper. But we are not left to

general conjecture in regard to the influence of Judas in this strife. There

is, we believe, ample evidence that he not only claimed, but actually obtained,

the chief seat at the table next to the Lord. This, as previously explained,

was not, as is generally believed, at the right, but at the left of Christ, not

below, but above Him, on the couches or pillows on which they reclined.

7. Wünsche

(on St. John xiii. 2) refers to Pes. 108 a, and states in a somewhat

general way that no order of rank was preserved at the Paschal Table. But the

passage he quotes does not imply this - only, that without distinction

of rank all sat down at the same table, but not that the well-established order

of sitting was infringed. The Jerusalem Talmud says nothing on the subject. The

Gospel-narrative, of course, expressly states that there was a

contention about rank among the disciples. In general, there are a number of

inaccuracies in the part of Wünsche's Notes referring to the Last

Supper.

8. St.

John xiii. 2

From the Gospel-narratives we infer, that St. John must have

reclined next to Jesus, on His Right Hand, since otherwise he could not have

leaned back on His Bosom. This, as we shall presently show, would be at one end

- the head of the table, or, to be more precise, at one end of the couches.

For, dismissing all conventional ideas, we must think of it as a low Eastern

table. In the Talmud,9

the table of the disciples of the sages is described as two parts covered with

a cloth, the other third being left bare for the dishes to stand on. There is

evidence that this part of the table was outside the circle of those who were

ranged around it. Occasionally a ring was fixed in it, by which the table was

suspended above the ground, so as to preserve it from any possible Levitical

defilement. During the Paschal Supper, it was the custom to remove the table at

one part of the service; or, if this be deemed a later arrangement, the dishes

at least would be taken off and put on again. This would render it necessary

that the end of the table should protrude beyond the line of guests who

reclined around it. For, as already repeatedly stated, it was the custom to

recline at table, lying on the left side and leaning on the left hand, the feet

stretching back towards the ground, and each guest occupying a separate divan

or pillow. It would, therefore, have been impossible to place or remove

anything from the table from behind the guests. Hence, as a matter of

necessity, the free end of the table, which was not covered with a cloth, would

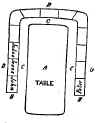

protrude beyond the line of those who reclined around it. We can now form a

picture of the arrangement. Around a low Eastern table, oval or rather

elongated, two parts covered with a cloth, and standing or else suspended, the

single divans or pillows are ranged in the form of an elongated horseshoe,

leaving free one end of the table, somewhat as in the accompanying woodcut.

Here A represents the table, B B respectively the ends of the two rows of

single divans on which each guest reclines on his left side, with his head (C)

nearest the table, and his feet (D) stretching back towards the ground.

9. B

Bathr 57 b.

Figure 5a.

So far for the arrangement of the table. Jewish documents are

equally explicit as to that of the guests. It seems to have been quite an

established rule10

that, in a company of more than two, say of three, the chief personage or Head

- in this instance, of course, Christ - reclined on the middle divan. We know

from the Gospel-narrative that John occupied the place on His right, at that

end of the divans - as we may call it - at the head of the table. But the chief

place next to the Master would be that to His left, or above Him. In the strife

of the disciples, which should be accounted the greatest, this had been

claimed, and we believe it to have been actually occupied, by Judas. This

explains how, Christ whispered to John by what sign to recognise the traitor,11

none of the other disciples heard it. It also explains, how Christ would first

hand to Judas the sop, which formed part of the Paschal ritual, beginning with

him as the chief guest at the table, without thereby exciting special notice.

Lastly, it accounts for the circumstance that, when Judas, desirous of

ascertaining whether his treachery was known, dared to ask whether it was he,

and received the affirmative answer,12

no one at table knew what had passed. But this could not have been the case,

unless Judas had occupied the place next to Christ; in this case, necessarily

that at His left, or the post of chief honour. As regards Peter, we can quite

understand how, when the Lord with such loving words rebuked their self-seeking

and taught them of the greatness of Christian humility, he should, in his

petuosity of shame, have rushed to take the lowest place at the other end of

the table.13 Finally,

we can now understand how Peter could beckon to John, who sat at the opposite

end of the table, over against him, and ask him across the table, who the

traitor was.14

The rest of the disciples would occupy such places as were most convenient, or

suited their fellowship with one another.

10. Ber.

46 b; Tos. Ber. v.; Jer. Taan, 68 a, towards the bottom.

11. St.

John xiii. 26.

12. St.

Matt. xxvi. 25.

13. It

seems almost incomprehensible, that Commentators, who have not thought this

narrative misplaced by St. Luke, should have attributed the strife to Peter and

John, the former being jealous of the place of honour which 'the beloved

Disciple' had obtained. (So Nebe, Leidensgesch.; the former even Calvin.)

14. St.

John xiii. 24.

The words which the Master spoke as He appeased their unseemly

strife must, indeed, have touched them to the quick. First, He showed them, not

so much in the language of even gentlest reproof as in that of teaching, the

difference between worldly honour and distinction in the Church of Christ. In

the world kingship lay in supremacy and lordship, and the title of Benefactor

accompanied the sway of power. But in the Church the 'greater' would not

exercise lordship, but become as the less and the younger [the latter referring

to the circumstance, that age next to learning was regarded among the Jews as a

claim to distinction and the chief seats]; while, instead of him that had

authority being called Benefactor, the relationship would be reversed, and he

that served would be chief. Self-forgetful humility instead of worldly glory,

service instead of rule: such was to be the title to greatness and to authority

in the Church.15

Having thus shown them the character and title to that greatness in the

Kingdom, which was in prospect for them, He pointed them in this respect also

to Himself as their example. The reference here is, of course, not to the act

of symbolic foot-washing, which St. Luke does not relate - although, as

immediately following on the words of Christ, it would illustrate them - but to

the tenor of His whole Life and the object of His Mission, as of One Who

served, not was served. Lastly, He woke them to the higher consciousness of

their own calling. Assuredly, they would not lose their reward; but not here,

nor yet now. They had shared, and would share His 'trials'16

- His being set at nought, despised, persecuted; but they would also share His

glory. As the Father had 'covenanted' to Him, so He 'covenanted' and bequeathed

to them a Kingdom, 'in order,' or 'so that,' in it they might have festive

fellowship of rest and of joy with Him. What to them must have been

'temptations,' and in that respect also to Christ, they had endured: instead of

Messianic glory, such as they may at first have thought of, they had witnessed

only contradiction, denial, and shame - and they had 'continued' with Him. But

the Kingdom was also coming. When His glory was manifested, their

acknowledgement would also come. Here Israel had rejected the King and His

Messengers, but then would that same Israel be judged by their word. A Royal

dignity this, indeed, but one of service; a full Royal acknowledgement, but one

of work. In that sense were Israel's Messianic hopes to be understood by them.

Whether or not something beyond this may also be implied, and, in that day when

He again gathers the outcasts of Israel, some special Rule and Judgment may be

given to His faithful Apostles, we venture not to determine. Sufficient for us

the words of Christ in their primary meaning.17

15. St.

Luke xxii. 25, 28.

16. Not

'temptation' - i.e. not assaults from within, but assaults from without.

17. The

'sitting down with Him' at the feast is evidently a promise of joy, reward, and

fellowship. The sitting on thrones and judging Israel must be taken as in

contrast to the 'temptation' of the contradiction of Christ and of their

Apostolic message - as their vindication against Israel's present gainsaying.

So speaking, the Lord commenced that Supper, which in itself

was symbol and pledge of what He had just said and promised. The Paschal Supper

began, as always,18

by the Head of the Company taking the first cup, and speaking over it

'the thanksgiving.' The form presently in use consists really of two

benedictions - the first over the wine, the second for the return of this

Feastday with all that it implies, and for being preserved once more to witness

it.19 Turning

to the Gospels, the words which follow the record of the benediction on the

part of Christ20

seem to imply, that Jesus had, at any rate, so far made use of the ordinary

thanksgiving as to speak both these benedictions. We know, indeed, that they

were in use before His time, since it was in dispute between the Schools of

Hillel and Shammai, whether that over the wine or that over the day should take

precedence. That over the wine was quite simple: 'Blessed art Thou, Jehovah our

God, Who hast created the fruit of the Vine!' The formula was so often used in

blessing the cup, and is so simple, that we need not doubt that these were the

very words spoken by our Lord. It is otherwise as regards the benediction 'over

the day,' which is not only more composite, but contains words expressive of

Israel's national pride and self-righteousness, such as we cannot think would

have been uttered by our Lord. With this exception, however, they were no doubt

identical in contents with the present formula. This we infer from what the

Lord added, as He passed the cup round the circle of the disciples.21

No more, so He told them, would He speak the benediction over the fruit of the

vine - not again utter the thanks 'over the day' that they had been 'preserved

alive, sustained, and brought to this season.' Another Wine, and at another

Feast, now awaited Him - that in the future, when the Kingdom would come. It

was to be the last of the old Paschas; the first, or rather the symbol and

promise, of the new. And so, for the first and last time, did He speak the

twofold benediction at the beginning of the Supper.

18. Pes.

x. 2.

19. The

whole formula is given in 'The Temple and its Services,' pp. 204, 205.

20. St.

Luke xxii. 17-18

21. I

have often expressed my conviction that in the ancient Services there was

considerable elasticity and liberty left to the individual. At present a cup is

filled for each individual, but Christ seems to have passed the one cup round

among the Disciples. Whether such was sometimes done, or the alteration was

designedly, and as we readily see, significantly, made by Christ, cannot now be

determined.

The cup, in which, according to express Rabbinic testimony,22

the wine had been mixed with water before it was 'blessed,' had passed round.

The next part of the ceremonial was for the Head of the Company to rise and

'wash hands.' It is this part of the ritual of which St. John23

records the adaptation and transformation on the part of Christ. The washing of

the disciples' feet is evidently connected with the ritual of 'handwashing.'

Now this was done twice during the Paschal Supper:24

the first time by the Head of the Company alone, immediately after the first

cup; the second time by all present, at a much later part of the service,

immediately before the actual meal (on the Lamb, &c.). If the footwashing

had taken place on the latter occasion, it is natural to suppose that, when the

Lord rose, all the disciples would have followed His example, and so the washing

of their feet would have been impossible. Again, the footwashing, which was

intended both as a lesson and as an example of humility and service,25

was evidently connected with the dispute 'which of them should be accounted to

be greatest.' If so, the symbolical act of our Lord must have followed close on

the strife of the disciples, and on our Lord's teaching what in the Church

constituted rule and greatness. Hence the act must have been connected with the

first handwashing - that by the Head of the Company - immediately after the

first cup, and not with that at a later period, when much else had intervened.

22. Babha

B. 97 b, lines 11 and 12 from top.

23. St.

John xiii.

24. Pes.

x. 4.

25. St.

John xiii. 12-16.

All else fits in with this. For clearness' sake, the account

given by St. John26

may here be recapitulated. The opening words concerning the love of Christ to

His own unto the end form the general introduction.27

Then follows the account of what happened 'during Supper'28

- the Supper itself being left undescribed - beginning, by way of explanation

of what is to be told about Judas, with this: 'The Devil having already cast

into his (Judas') heart, that Judas Iscariot, the son of Simon, shall betray

Him.' General as this notice is, it contains much that requires special

attention. Thankfully we feel, that the heart of man was not capable of

originating the Betrayal of Christ; humanity had fallen, but not so low. It was

the Devil who had 'cast' it into Judas' heart - with force and overwhelming

power.29 Next, we

mark the full description of the name and parentage of the traitor. It reads

like the wording of a formal indictment. And, although it seems only an

introductory explanation, it also points to the contrast with the love of

Christ which persevered to the end,30

even when hell itself opened its mouth to swallow Him up; the contrast, also,

between what Jesus and what Judas were about to do, and between the wild storm

of evil that raged in the heart of the traitor and the calm majesty of love and

peace which reigned in that of the Saviour.

26. St.

John xiii.

27. Godet,

who regards ver. 1 as a general, and ver. 2 as a special, introduction to the

foot-washing, calls attention to the circumstance that such introductions not

unfrequently occur in the Fourth Gospel.

28. ver.

2.

29. The

contrast is the more marked as the same verb (ballein)

is used both of Satan 'casting' it into the heart of Judas, and of Christ

throwing into the basin the water for the footwashing.

30. St.

John xiii.1

If what Satan had cast into the heart of Judas explains his

conduct so does the knowledge which Jesus possessed account for that He was

about to do.31

32

Many as are the thoughts suggested by the words, 'Knowing that the Father had

given all things into His Hands, and that He came forth from God, and goeth

unto God' - yet, from evident connection, they must in the first instance be

applied to the Footwashing, of which they are, so to speak, the logical

antecedent. It was His greatest act of humiliation and service, and yet He

never lost in it for one moment aught of the majesty or consciousness of His

Divine dignity; for He did it with the full knowledge and assertion that all

things were in His Hands, and that He came forth from and was going unto God -

and He could do it, because He knew this. Here, not side by side, but in

combination, are the Humiliation and Exaltation of the God-Man. And so, 'during

Supper,' which had begun with the first cup, 'He riseth from Supper.' The

disciples would scarcely marvel, except that He should conform to that practice

of handwashing, which, as He had often explained, was, as a ceremonial

observance, unavailing for those who were not inwardly clean, and needless and

unmeaning in them whose heart and life had been purified. But they must have

wondered as they saw Him put off His upper garment, gird Himself with a towel,

and pour water into a basin, like a slave who was about to perform the meanest

service.

31. St.

John xi.

32. Bengel:

magna vis.

From the position which, as we have shown, Peter occupied at

the end of the table, it was natural that the Lord should begin with him the

act of footwashing.33

Besides, had He first turned to others, Peter must either have remonstrated

before, or else his later expostulation would have been tardy, and an act

either of self-righteousness or of needless voluntary humility. As it was, the

surprise with which he and the others had witnessed the preparation of the Lord

burst into characteristic language when Jesus approached him to wash his feet.

'Lord - Thou - of me washest the feet!' It was the utterance of deepest

reverence for the Master, and yet of utter misunderstanding of the meaning of

His action, perhaps even of His Work. Jesus was now doing what before He had

spoken. The act of externalism and self-righteousness represented by the

washing of hands, and by which the Head of the Company was to be distinguished

from all others and consecrated, He changed into a footwashing, in which the

Lord and Master was to be distinguished, indeed, from the others - but by the

humblest service of love, and in which He showed by His example what characterised

greatness in the Kingdom, and that service was evidence of rule. And, as mostly

in every symbol, there was the real also in this act of the Lord. For, by

sympathetically sharing in this act of love and service on the part of the

Lord, they who had been bathed - who had previously become clean in heart and

spirit - now received also that cleansing of the 'feet,' of active and daily

walk, which cometh from true heart-humility, in opposition to pride, and

consisteth in the service which love is willing to render even to the

uttermost.

33. St.

Chrysostom and others unduly urge the words (ver. 6), 'He cometh to

Peter.' He came to him, not after the others, but from the place where the

basin and water for the purification had stood.

But Peter had understood none of these things. He only felt the

incongruousness of their relative positions. And so the Lord, partly also

wishing thereby to lead his impetuosity to the absolute submission of faith,

and partly to indicate the deeper truth he was to learn in the future, only

told him, that though he knew it not now, he would understand hereafter what

the Lord was doing. Yes, hereafter - when, after that night of terrible fall,

he would learn by the Lake of Galilee what it really meant to feed the lambs

and to tend the sheep of Christ; yes, hereafter - when no longer, as when he

had been young, he would gird himself and walk whither he would. But, even so,

Peter could not content himself with the prediction that in the future he would

understand and enter into what Christ was doing in washing their feet. Never,

he declared, could he allow it. The same feelings, which had prompted him to

attempt withdrawing the Lord from the path of humiliation and suffering,34

now asserted themselves again. It was personal affection, indeed, but it was

also unwillingness to submit to the humiliation of the Cross. And so the Lord

told him, that if He washed him not, he had no part with Him. Not that the bare

act of washing gave him part in Christ, but that the refusal to submit to it

would have deprived him of it; and that, to share in this washing, was, as it

were, the way to have part in Christ's service of love, to enter into it, and

to share it.

34. St.

Matt. xv. 22.

Still, Peter did not understand. But as, on that morning by the

Lake of Galilee, it appeared that, when he had lost all else, he had retained

love, so did love to the Christ now give him the victory - and, once more with

characteristic impetuosity, he would have tendered not only his feet to be

washed, but his hands and head. Yet here, also, was there misunderstanding.

There was deep symbolical meaning, not only in that Christ did it, but

also in what He did. Submission to His doing it meant symbolically share

and part with Him - part in His Work. What He did, meant His work and

service of love; the constant cleansing of one's walk and life in the love of

Christ, and in the service of that love. It was not a meaningless ceremony of

humiliation on the part of Christ, not yet one where submission to the utmost

was required; but the action was symbolic, and meant that the disciple, who was

already bathed and made clean in heart and spirit, required only this - to wash

his feet in spiritual consecration to the service of love which Christ had here

shown forth in symbolic act. And so His Words referred not, as is so often

supposed, to the forgiveness of our daily sins - the introduction of which

would have been wholly abrupt and unconnected with the context - but, in

contrast to all self-seeking, to the daily consecration of our life to the

service of love after the example of Christ.

And still do all these words come to us in manifold and

ever-varied application. In the misunderstanding of our love to Him, we too

often imagine that Christ cannot will or do what seems to us incongruous on His

part, or rather, incongruous with what we think about Him. We know it not now,

but we shall understand it hereafter. And still we persist in our resistance,

till it comes to us that so we would even lose our part in and with Him. Yet

not much, not very much, does He ask, Who giveth so much. He that has washed us

wholly would only have us cleanse our feet for the service of love, as He gave

us the example.

They were clean, these disciples, but not all. For He knew that

there was among them he 'that was betraying Him.'35

He knew it, but not with the knowledge of an inevitable fate impending far less

of an absolute decree, but with that knowledge which would again and again

speak out the warning, if by any means he might be saved. What would have come,

if Judas had repented, is as idle a question as this: What would have come if

Israel, as a nation, had repented and accepted Christ? For, from our human

standpoint, we can only view the human aspect of things - that earthwards; and

here every action is not isolated, but ever the outcome of a previous

development and history, so that a man always freely acts, yet always in

consequence of an inward necessity.

35. So

the expression in St. John xiii. 11, more accurately rendered.

The solemn service of Christ now went on in the silence of reverent

awe.36 None

dared ask Him nor resist. It was ended, and He had resumed His upper garment,

and again taken His place at the Table. It was His now to follow the symbolic

deed by illustrative words, and to explain the practical application of what

had just been done. Let it not be misunderstood. They were wont to call Him by

the two highest names of Teacher and Lord, and these designations were rightly

His. For the first time He fully accepted and owned the highest homage. How

much more, then, must His Service of love, Who was their Teacher and Lord,

serve as example37

of what was due38

by each to his fellow-disciple and fellow-servant! He, Who really was Lord and

Master, had rendered this lowest service to them as an example that, as He had

done, so should they do. No principle better known, almost proverbial in

Israel, than that a servant was not to claim greater honour than his master,

nor yet he that was sent than he who had sent him. They knew this, and now also

the meaning of the symbolic act of footwashing; and if they acted it out, then

theirs would be the promised 'Beatitude.'39

36. St.

John xiii. 12-17.

37. upodeigma. The distinctive meaning of

the word is best gathered from the other passages in the N.T. in which it

occurs, viz. Heb. iv. 11; viii. 5; ix. 23; St. James v. 10; 2 Pet. ii. 6. For

the literal outward imitation of this deed of Christ in the ceremony of

footwashing, still common in the Roman Catholic Church, see Bingham,

Antiq. xii. 4, 10.

38. ofeilete.

39. The

word is that employed in the 'Beatitudes,' makarioi.

This reference to what were familiar expressions among the

Jews, especially noteworthy in St. John's Gospel, leads us to supplement a few

illustrative notes from the same source. The Greek word for 'the towel,' with

which our Lord girded Himself, occurs also in Rabbinic writings, to denote the

towel used in washing and at baths (Luntith and Aluntith). Such

girding was the common mark of a slave, by whom the service of footwashing was

ordinarily performed. And, in a very interesting passage, the Midrash40

contrasts what, in this respect, is the way of man with what God had done for

Israel. For, He had been described by the prophet as performing for them the

service of washing,41

and others usually rendered by slaves.42

Again, the combination of these two designations, 'Rabbi and Lord,' or 'Rabbi,

Father, and Lord,' was among those most common on the part of disciples.43

The idea, that if a man knows (for example, the Law) and does not do it, it

were better for him not to have been created,44

is not unfrequently expressed. But the most interesting reference is in regard

to the relation between the sender and the sent, and a servant and his master.

In regard to the former, it is proverbially said, that while he that is sent

stands on the same footing as he who sent him,45

yet he must expect less honour.46

And as regards Christ's statement that 'the servant is not greater than his

Master,' there is a passage in which we read this, in connection with the

sufferings of the Messiah: 'It is enough for the servant that he be like

his Master.'47

40. Shem.

R. 20.

41. Ezek.

xvi. 9.

42. Comp.

Ezek. xvi. 10; Ex. xix. 4; xiii. 21.

43. ynwd)w yb) ybr

or yrwmw ybr.

44. Comp.

St. John xiii. 17.

45. Kidd,

42 a.

46. Ber.

R. 78.

47. Yalkut

on Is. ix. vol. ii. p. 56 d, lines 12, 13 from top.

But to return. The footwashing on the part of Christ, in which

Judas had shared, together with the explanatory words that followed, almost

required, in truthfulness, this limitation: 'I speak not of you all.' For it

would be a night of terrible moral sifting to them all. A solemn warning was

needed by all the disciples. But, besides, the treachery of one of their own

number might have led them to doubt whether Christ had really Divine knowledge.

On the other hand, this clear prediction of it would not only confirm their

faith in Him, but show that there was some deeper meaning in the presence of a

Judas among them.48

We come here upon these words of deepest mysteriousness: 'I know those I chose;

but that the Scripture may be fulfilled, He that eateth My Bread lifteth up his

heel against Me!'49

It were almost impossible to believe, even if not forbidden by the context,

that this knowledge of which Christ spoke, referred to an eternal

foreknowledge; still more, that it meant Judas had been chosen with such

foreknowledge in order that this terrible Scripture might be fulfilled in him.

Such foreknowledge and foreordination would be to sin, and it would involve

thoughts such as only the harshness of our human logic in its fatal

system-making could induce anyone to entertain. Rather must we understand it as

meaning that Jesus had, from the first, known the inmost thoughts of those He

had chosen to be His Apostles; but that by this treachery of one of their

number, the terrible prediction of the worst enmity, that of ingratitude, true

in all ages of the Church, would receive its complete fulfilment.50

The word 'that' - 'that the Scripture may be fulfilled,' does not mean

'in order that,' or 'for the purpose of;' it never means this in that

connection;51

and it would be altogether irrational to suppose that an event happened in

order that a special prediction might be fulfilled. Rather does it indicate

the higher internal connection in the succession of events, when an event had

taken place in the free determination of its agents, by which, all

unknown to them and unthought of by others, that unexpectedly came to pass

which had been Divinely foretold. And herein appears the Divine character of

prophecy, which is always at the same time announcement and forewarning, that

is, has besides its predictive a moral element: that, while man is left to act

freely, each development tends to the goal Divinely foreseen and foreordained.

Thus the word 'that' marks not the connection between causation and effect, but

between the Divine antecedent and the human subsequent.

48. St.

John xiii. 18, 19.

49. Ps.

xli. 9.

50. At

the same time there is also a terrible literality about this prophetic

reference to one who ate his bread, when we remember that Judas, like the rest,

lived of what was supplied to Christ, and at that very moment sat at His Table.

On Ps. xli. see the Commentaries.

51. 'ina frequenter ekbatikwV, i.e. de eventu usurpari dicitur, ut sit

eo eventu, ut; eo successu, ut, ita ut' [Grimm, ad verb.] - Angl.

'so that.' And Grimm rightly points out that ina is always used in that sense, marking the

internal connection in the succession of events - ekbatikwV not telikwV

- where the phrase occurs 'that it might be fulfilled.' This canon is most

important, and of very wide application wherever the ina is connected with the Divine Agency, in which, from

our human view-point, we have to distinguish between the decree and the counsel

of God.

There is, indeed, behind this a much deeper question, to which

brief reference has already formerly been made. Did Christ know from the

beginning that Judas would betray Him, and yet, so knowing, did He choose him

to be one of the Twelve? Here we can only answer by indicating this as a canon

in studying the Life on earth of the God-Man, that it was part of His Self-examination - of that emptying Himself, and taking upon Him the form of a

Servant52 -

voluntarily to forego His Divine knowledge in the choice of His Human actions.

So only could He, as perfect Man, have perfectly obeyed the Divine Law. For, if

the Divine had determined Him in the choice of His Actions, there could have

been no merit attaching to His Obedience, nor could He be said to have, as

perfect Man, taken our place, and to have obeyed the Law in our stead and as

our Representative, nor yet be our Ensample. But if His Divine knowledge did

not guide Him in the choice of His actions, we can see, and have already

indicated, reasons why the discipleship and service of Judas should have been

accepted, if it had been only as that of a Judæan, a man in many respects well

fitted for such an office, and the representative of one of the various

directions which tended towards the reception of the Messiah.

52. Phil.

ii. 5-7.

We are not in circumstances to judge whether or not Christ

spoke all these things continuously, after He had sat down, having washed the

disciples' feet. More probably it was at different parts of the meal. This

would also account for the seeming abruptness of this concluding sentence:53

'He that receiveth whomsoever I send receiveth Me.' And yet the internal

connection of thought seems clear. The apostasy and loss of one of the Apostles

was known to Christ. Would it finally dissolve the bond that bound together the

College of Apostles, and so invalidate their Divine Mission (the Apostolate)

and its authority? The words of Christ conveyed an assurance which would be

most comforting in the future, that any such break would not be lasting, only

transitory, and that in this respect also 'the foundation of God standeth.'

53. St.

John xiii. 20.

In the meantime the Paschal Supper was proceeding. We mark this

important note of time in the words of St. Matthew: 'as they were eating,'54

or, as St. Mark expresses it, 'as they reclined and were eating.'55

According to the Rubric, after the 'washing' the dishes were immediately to be

brought on the table. Then the Head of the Company would dip some of the bitter

herbs into the salt-water or vinegar, speak a blessing, and partake of them,

then hand them to each in the company. Next, he would break one of the

unleavened cakes (according to the present ritual the middle of the three), of

which half was put aside for after supper. This is called the Aphiqomon,

or after-dish, and as we believe that 'the bread' of the Holy Eucharist was the

Aphiqomon, some particulars may here be of interest. The dish in which

the broken cake lies (not the Aphiqomon), is elevated, and these words

are spoken: 'This is the bread of misery which our fathers ate in the land of

Egypt. All that are hungry, come and eat; all that are needy, come, keep the

Pascha.' In the more modern ritual the words are added: 'This year here, next

year in the land of Israel; this year bondsmen, next year free!' On this the

second cup is filled, and the youngest in the company is instructed to make

formal inquiry as to the meaning of all the observances of that night,56

when the Liturgy proceeds to give full answers as regards the festival, its

occasion, and ritual. The Talmud adds that the table is to be previously

removed, so as to excite the greater curiosity.57

We do not suppose that even the earlier ritual represents the exact observances

at the time of Christ, or that, even if it does so, they were exactly followed

at that Paschal Table of the Lord. But so much stress is laid in Jewish

writings on the duty of fully rehearsing at the Paschal Supper the circumstances

of the first Passover and the deliverance connected with it, that we can

scarcely doubt that what the Mishnah declares as so essential formed part of

the services of that night. And as we think of our Lord's comment on the

Passover and Israel's deliverance, the words spoken when the unleavened cake

was broken come back to us, and with deeper meaning attaching to them.

54. St.

Matt. xxvi. 21.

55. St.

Mark xiv. 18.

56. Pes.

x. 4.

57. Pes.

115 b.

After this the cup is elevated, and then the service proceeds

somewhat lengthily, the cup being raised a second time and certain prayers spoken.

This part of the service concludes with the two first Psalms in the series

called 'the Hallel,'58

when the cup is raised a third time, a prayer spoken, and the cup drunk. This

ends the first part of the service. And now the Paschal meal begins by all

washing their hands - a part of the ritual which we scarcely think Christ

observed. It was, we believe, during this lengthened exposition and service

that the 'trouble in spirit' of which St. John speaks59

passed over the soul of the God-Man. Almost presumptuous as it seems to inquire

into its immediate cause, we can scarcely doubt that it concerned not so much

Himself as them. His Soul could not, indeed, but have been troubled, as, with

full consciousness of all that it would be to Him - infinitely more than merely

human suffering - He looked down into the abyss which was about to open at His

Feet. But He saw more than even this. He saw Judas about to take the last fatal

step, and His Soul yearned in pity over him. The very sop which He would so

soon hand to him, although a sign of recognition to John, was a last appeal to

all that was human in Judas. And, besides all this, Jesus also saw, how, all

unknown to them, the terrible tempest of fierce temptation would that night

sweep over them; how it would lay low and almost uproot one of them, and

scatter all. It was the beginning of the hour of Christ's utmost loneliness, of

which the climax was reached in Gethsemane. And in the trouble of His Spirit

did He solemnly 'testify' to them of the near Betrayal. We wonder not, that

they all became exceeding sorrowful, and each asked, 'Lord, is it I?' This

question on the part of the eleven disciples, who were conscious of innocence

of any purpose of betrayal, and conscious also of deep love to the Master,

affords one of the clearest glimpses into the inner history of that Night of

Terror, in which, so to speak, Israel became Egypt. We can now better

understand their heavy sleep in Gethsemane, their forsaking Him and fleeing,

even Peter's denial. Everything must have seemed to these men to give way; all

to be enveloped in outer darkness, when each man could ask whether he was to be

the Betrayer.

58. Ps.

cxiii to cxviii.

59. St.

John xiii. 21.

The answer of Christ left the special person undetermined,

while it again repeated the awful prediction - shall we not add, the most

solemn warning - that it was one of those who took part in the Supper. It is at

this point that St. John resumes the thread of the narrative.60

As he describes it, the disciples were looking one on another, doubting of whom

He spake. In this agonising suspense Peter beckoned from across the table to

John, whose head, instead of leaning on his hand, rested, in the absolute

surrender of love and intimacy born of sorrow, on the bosom of the Master.61

Peter would have John ask of whom Jesus spake.62

And to the whispered question of John, 'leaning back as he was on Jesus'

breast,' the Lord gave the sign, that it was he to whom He would give 'the sop'

when He had dipped it. Even this perhaps was not clear to John, since each one

in turn received 'the sop.'

60. St.

John xiii. 22.

61. The

reading adopted in the R.V. of St. John xiii. 24 represents the better

accredited text, though it involves some difficulties.

62. On

the circumstance that John does not name himself in ver. 23, Bengel

beautifully remarks: 'Optabilius est, amari ab Jesu, quam nomine proprio

celebrari.'

At present, the Supper itself begins by eating, first, a piece

of the unleavened cake, then of the bitter herbs dipped in Charoseth,

and lastly two small pieces of the unleavened cake, between which a piece of

bitter radish has been placed. But we have direct testimony, that, about the

time of Christ,63

'the sop'64 which was

handed round consisted of these things wrapped together: flesh of the Paschal

Lamb, a piece of unleavened bread, and bitter herbs.65

This, we believe, was 'the sop,' which Jesus, having dipped it for him in the

dish, handed first to Judas, as occupying the first and chief place at Table.

But before He did so, probably while He dipped it in the dish, Judas, who could

not but fear that his purpose might be known, reclining at Christ's left hand,

whispered into the Master's ear, 'Is it I, Rabbi?' It must have been whispered,

for no one at the Table could have heard either the question of Judas or the

affirmative answer of Christ.66

It was the last outgoing of the pitying love of Christ after the traitor.

Coming after the terrible warning and woe on the Betrayer,67

it must be regarded as the final warning and also the final attempt at rescue

on the part of the Saviour. It was with full knowledge of all, even of this

that his treachery was known, though he may have attributed the information not

to Divine insight but to some secret human communication, that Judas went on

his way to destruction. We are too apt to attribute crimes to madness; but

surely there is normal, as well as mental mania; and it must have been in a

paroxysm of that, when all feeling was turned to stone, and mental

self-delusion was combined with moral perversion, that Judas 'took'68

from the Hand of Jesus 'the sop.' It was to descend alive into the grave - and

with a heavy sound the gravestone fell and closed over the mouth of the pit.

That moment Satan entered again into his heart. But the deed was virtually

done; and Jesus, longing for the quiet fellowship of His own with all that was

to follow, bade him do quickly that he did.

63. The

statement is in regard to Hillel, while the Temple stood.

64. Mark

the definite article - not 'a sop.'

65. Jer. Chall.

57 b.

66. St.

John xiii. 28.

67. St.

Matt. xxvi. 24; St. Mark xiv. 21.

68. St.

John xiii. 30 should be rendered, 'having taken,' not 'received.'

But even so there are questions connected with the human

motives that actuated Judas, to which, however, we can only give the answer of

some suggestions. Did Judas regard Christ's denunciation of 'woe' on the

Betrayer not as a prediction, but as intended to be deterrent - perhaps in

language Orientally exaggerated - or if he regarded it as a prediction, did he

not believe in it? Again, when after the plain intimation of Christ and His

Words to do quickly what he was about to do, Judas still went to the betrayal,

could he have had an idea - rather, sought to deceive himself, that Jesus felt

that He could not escape His enemies, and that He rather wished it to be all

over? Or had all his former feelings towards Jesus turned, although

temporarily, into actual hatred which every Word and Warning of Christ only

intensified? But above all and in all we have, first and foremost, to think of

the peculiarly Judaic character of his first adherence to Christ; of the

gradual and at last final and fatal disenchantment of his hopes; of his utter

moral, consequent upon his spiritual, failure; of the change of all that had in

it the possibility of good into the actuality of evil; and, on the other hand,

of the direct agency of Satan in the heart of Judas, which his moral and spiritual

ship-wreck rendered possible.

From the meal scarcely begun Judas rushed into the dark night.

Even this has its symbolic significance. None there knew why this strange

haste, unless from obedience to something that the Master had bidden him.69

Even John could scarcely have understood the sign which Christ had given of the

traitor. Some of them thought, he had been directed by the words of Christ to

purchase what was needful for the feast: others, that he was bidden go and give

something to the poor. Gratuitous objection has been raised, as if this

indicated that, according to the Fourth Gospel, this meal had not taken place

on the Paschal night, since, after the commencement of the Feast (on the 15th

Nisan), it would be unlawful to make purchases. But this certainly was not the

case. Sufficient here to state, that the provision and preparation of the

needful food, and indeed of all that was needful for the Feast, was allowed on

the 15th Nisan.70

And this must have been specially necessary when, as in this instance, the

first festive day, or 15th Nisan, was to be followed by a Sabbath, on which no

such work was permitted. On the other hand, the mention of these two

suggestions by the disciples seems almost necessarily to involve, that the

writer of the Fourth Gospel had placed this meal in the Paschal Night. Had it

been on the evening before, no one could have imagined that Judas had gone out

during the night to buy provisions, when there was the whole next day for it,

nor would it have been likely that a man should on any ordinary day go at such

an hour to seek out the poor. But in the Paschal Night, when the great

Temple-gates were opened at midnight to begin early preparations for the

offering of the Chagigah, or festive sacrifice, which was not voluntary but

of due, and the remainder of which was afterwards eaten at a festive meal, such

preparations would be quite natural. And equally so, that the poor, who

gathered around the Temple, might then seek to obtain the help of the

charitable.

69. To

a Jew it might seem that with the 'sop,' containing as it did a piece of the

Paschal Lamb, the chief part in the Paschal Supper was over.

70. The

Mishnah expressly allows the procuring even on the Sabbath of that which is

required for the Passover, and the Law of the Sabbath-rest was much more strict

than that of feast-days. See this in Appendix XVII., p. 783.

The departure of the betrayer seemed to clear the atmosphere.

He was gone to do his work; but let it not be thought that it was the necessity

of that betrayal which was the cause of Christ's suffering of soul. He offered

Himself willingly - and though it was brought about through the treachery of

Judas, yet it was Jesus Himself Who freely brought Himself a Sacrifice, in

fulfilment of the work which the Father had given Him. And all the more did He

realise and express this on the departure of Judas. So long as he was there, pitying

love still sought to keep him from the fatal step. But when the traitor was at

last gone, the other side of His own work clearly emerged into Christ's view.

And this voluntary sacrificial aspect is further clearly indicated by His

selection of the terms 'Son of Man' and 'God' instead of 'Son' and 'Father.'71

'Now is glorified the Son of Man, and God is glorified in Him.72

And God shall glorify Him in Himself, and straightway shall He glorify Him.' If

the first of these sentences expressed the meaning of what was about to take

place, as exhibiting the utmost glory of the Son of Man in the triumph of the

obedience of His Voluntary Sacrifice, the second sentence pointed out its

acknowledgment by God: the exaltation which followed the humiliation, the reward73

as the necessary sequel of the work, the Crown after the Cross.

71. St.

John.

72. The

first in ver. 32 of our T.R. seems spurious, though it indicates the logical nexus

of facts.

73. Probably

the word 'reward' is wrongly chosen, for I look on Christ's exaltation after

the victory of His Obedience as rather the necessary sequence than the reward

of His Work.

Thus far for one aspect of what was about to be enacted. As for

the other - that which concerned the disciples: only a little while would He

still be with them. Then would come the time of sad and sore perplexity - when

they would seek Him, but could not come whither He had gone - during the

terrible hours between His Crucifixion and His manifested Resurrection. With

reference to that period especially, but in general to the whole time of His

Separation from the Church on earth, the great commandment, the bond which

alone would hold them together, was that of love one to another, and such love

as that which He had shown towards them. And this - shame on us, as we write

it! - was to be the mark to all men of their discipleship.74

As recorded by St. John, the words of the Lord were succeeded by a question of

Peter, indicating perplexity as to the primary and direct meaning of Christ's

going away. On this followed Christ's reply about the impossibility of Peter's

now sharing his Lord's way of Passion, and, in answer to the disciple's

impetuous assurance of his readiness to follow the Master not only into peril,

but to lay down his Life for Him, the Lord's indication of Peter's present

unpreparedness and the prediction of His impending denial. It may have been,

that all this occurred in the Supper-Chamber and at the time indicated by St.

John. But it is also recorded by the Synoptists as on the way to Gethsemane,

and in, what we may term, a more natural connection. Its consideration will

therefore be best reserved till we reach that stage of the history.

74. St.

John xiii. 31-35.

We now approach the most solemn part of that night: The

Institution of the Lord's Supper. It would manifestly be beyond the object, as

assuredly it would necessarily stretch beyond the limits, of the present work,

to discuss the many questions and controversies which, alas! have gathered

around the Words of the Institution. On the other hand, it would not be

truthful wholly to pass them by. On certain points, indeed, we need have no

hesitation. The Institution of the Lord's Supper is recorded by the Synoptists,

although without reference to those parts of the Paschal Supper and its

Services with which one or another of its acts must be connected. In fact,

while the historical nexus with the Paschal Supper is evident, it almost

seems as if the Evangelists had intended, by their studied silence in regard to

the Jewish Feast, to indicate that with this Celebration and the new

Institution the Jewish Passover had for ever ceased. On the other hand, the

Fourth Gospel does not record the new Institution - it may have been, because

it was so fully recorded by the others; or for reasons connected with the

structure of that Gospel; or it may be accounted for on other grounds.75

But whatever way we may account for it, the silence of the Fourth Gospel must

be a sore difficulty to those who regard it as an Ephesian product of

symbolico-sacramentarian tendency, dating from the second century.

75. Could

there possibly be a hiatus in our present Gospel? There is not the least

external evidence to that effect, and yet the impression deepens on

consideration.

The absence of a record by St. John is compensated by the

narrative of St Paul in 1 Cor. xi. 23-26, to which must be added as

supplementary the reference in 1 Cor. x. 16 to 'the Cup of Blessing which we

bless' as 'fellowship of the Blood of Christ, and the Bread which we break' as 'fellowship

of the Body of Christ.' We have thus four accounts, which may be divided into

two groups: St Matthew and St. Mark, and St. Luke and St. Paul. None of these

give us the very words of Christ, since these were spoken in Aramæan. In the

renderings which we have of them one series may be described as the more rugged

and literal, the other as the more free and paraphrastic. The differences

between them are, of course, exceedingly minute; but they exist. As regards the

text which underlies the rendering in our A.V., the difference suggested are

not of any practical importance,76

with the exception of two points. First, the copula 'is' ['This is My

Body,' 'This is My Blood'] was certainly not spoken by the Lord in the

Aramaic, just as it does not occur in the Jewish formula in the breaking of

bread at the beginning of the Paschal Supper. Secondly, the words: 'Body which

is given,' or, in 1 Cor. xi. 24, 'broken,' and 'Blood which is shed,' should be

more correctly rendered: 'is being given,' 'broken,' 'shed.'

76. The

most important of these, perhaps, is the rendering of 'covenant' for

'testament.' In St. Matthew the word 'new' before 'covenant,' should be left

out; this also in St. Mark, as well as the word 'eat' after 'take.'

If we now ask ourselves at what part of the Paschal Supper the

new Institution was made, we cannot doubt that it was before the Supper was

completely ended.77

We have seen, that Judas had left the Table at the beginning of the Supper. The

meal continued to its end, amidst such conversation as has already been noted.

According to the Jewish ritual, the third Cup was filled at the close of

the Supper. This was called, as by St. Paul,78

'the Cup of Blessing,' partly, because a special 'blessing' was pronounced over

it. It is described as one of the ten essential rites in the Paschal Supper.

Next, 'grace after meat' was spoken. But on this we need not dwell, nor yet on

'the washing of hands' that followed. The latter would not be observed by Jesus

as a religious ceremony; while, in regard to the former, the composite

character of this part of the Paschal Liturgy affords internal evidence that it

could not have been in use at the time of Christ. But we can have little doubt,

that the Institution of the Cup was in connection with this third 'Cup of

Blessing.'79 If we are

asked, what part of the Paschal Service corresponds to the 'Breaking of Bread,'

we answer, that this being really the last Pascha, and the cessation of it, our

Lord anticipated the later rite, introduced when, with the destruction of the

Temple, the Paschal as all other Sacrifices ceased. While the Paschal Lamb was

still offered, it was the Law that, after partaking of its flesh, nothing else

should be eaten. But since the Paschal Lamb had ceased, it is the custom after

the meal to break and partake as Aphikomon, or after-dish, of that half

of the unleavened cake, which, as will be remembered, had been broken and put

aside at the beginning of the Supper. The Paschal Sacrifice having now really

ceased, and consciously so to all the disciples of Christ, He anticipated this,

and connected with the breaking of the Unleavened Cake at the close of the Meal

the institution of the breaking of Bread in the Holy Eucharist.

77. St.

Matt. xxvi. 26; St. Mark xiv. 22.

78. 1

Cor. x. 10.

79. Though,

of course, most widely differing from what is an attempt to trace an analogy

between the Ritual of the Romish Mass and the Paschal Liturgy of the Jews, the

article on it by the learned Professor Bickell, of Innsbruck, possesses

a curious interest. See Zeitsch. fur Kathol. Theol. for 1880, pp. 90-112.

What did the Institution really mean, and what does it mean to

us? We cannot believe that it was intended as merely a sign for remembrance of

His Death. Such remembrance is often equally vivid in ordinary acts of faith or

prayer; and it seems difficult, if no more than this had been intended, to

account for the Institution of a special Sacrament, and that with such

solemnity, and as the second great rite of the Church - that for its

nourishment. Again, if it were a mere token of remembrance, why the Cup as well

as the Bread? Nor can we believe, that the copula 'is' - which, indeed,

did not occur in the words spoken by Christ Himself - can be equivalent to 'signifies.'

As little can it refer to any change of substance, be it in what is called

Transubstantiation or Consubstantiation. If we may venture an explanation, it

would be that 'this,' received in the Holy Eucharist, conveys to the soul as

regards the Body and Blood of the Lord, the same effect as the Bread and the

Wine to the body - receiving of the Bread and the Cup in the Holy Communion is,

really, though spiritually, to the Soul what the outward elements are to the

Body: that they are both the symbol and the vehicle of true, inward, spiritual

feeding on the Very Body and Blood of Christ. So is this Cup which we bless

fellowship of His Blood, and the Bread we break of His Body - fellowship with

Him Who died for us, and in His dying; fellowship also in Him with one another,

who are joined together in this, that for us this Body was given, and for the

remission of our sins this precious Blood was shed.80

80. I

would here refer to the admirable critical notes on 1 Cor. x. and xi. by

Professor Evans in 'The Speaker's Commentary.'

Most mysterious words these, yet most blessed mystery this of

feeding on Christ spiritually and in faith. Most mysterious - yet 'he who takes

from us our mystery takes from us our Sacrament.'81

And ever since has this blessed Institution lain as the golden morning-light

far out even in the Church's darkest night - not only the seal of His Presence

and its pledge, but also the promise of the bright Day at His Coming. 'For as

often as we eat this Bread and drink this Cup, we do show forth the Death of

the Lord' - for the life of the world, to be assuredly yet manifested - 'till

He come.' 'Even so, Lord Jesus, come quickly!'

81. The

words area hitherto unprinted utterance on this subject by the late Professor J.

Duncan, of Edinburgh.

Chapter 9 | Table

of Contents | Chapter 11

research-bpr@philologos.org

|